The Unmitigated Mastery (and Mystery) of the Late, Great Allan Holdsworth

The iconic, unprecedented guitar genius would've turned 79 today

“I really never wanted to be a guitar player,” I remember Allan telling me in a Downbeat interview from 40 years ago. “I’m a guitar player because I was given a guitar as a young boy and I began dabbling on it and eventually got into it. I always loved music as a kid, but the instrument I really wanted to play was the saxophone. I've always wanted to play a wind instrument of some kind, be it a wind instrument that exists now or one that is played on some other planet somewhere…I dunno.”

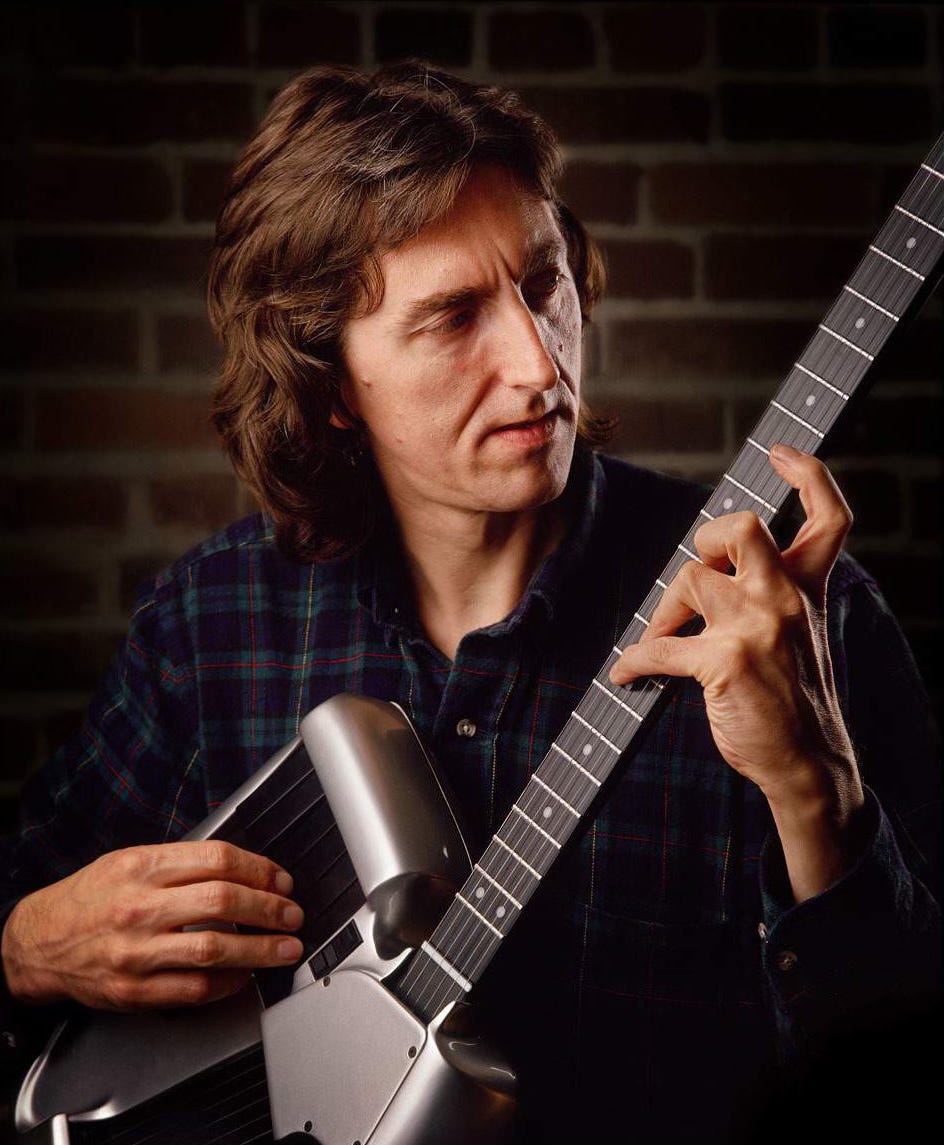

The kind of unprecedented experimentation that Holdsworth did on his chosen instrument — first on a regular six-string axe and eventually on a Star Trek-looking SynthAxe MIDI contraption with breath controller tubing that enabled him to activate sounds by blowing, like a sax player — was indeed otherwordly.

That he was born with uncannily long fingers allowing for uncommon stretches across the fretboard was a given with this bona fide genius. But it was the expansive nature of his curious mind and inner urge to explore his chosen instrument like a sonic Magellan that pushed the soft-spoken Yorkshire lad quite literally “to go where no man has gone before.”

For instance, dig this snippet of conversation from a much longer interview that I conducted with Allan in 2005 for the Abstract Logix website:

Does hearing other musicians have an impact on your own writing? Definitely, yeah. For example, I went to see John Scofield when he was playing at the Musicians Institute in California about five or six years ago. Gary Willis was playing bass with him and it was beautiful and incredible. Then I went home and wrote this piece of music called “Above and Below,” which took me a few days to complete. And that was a direct result of hearing him play, although it sounds nothing like how he plays.

Because it’s filtered through your own aesthetic. Yeah, I do that a lot. I get a lot from everybody. Even things that don’t have anything to do with music. Just seeing certain things — a plant, a tree, a mountain or a big building — where it kind of gives you a feeling. Or movies too. I always wanted to do that, put music to movies. I think it would be too complicated for me to do it, in terms of all the technical stuff that goes on…the way that it’s done. But I definitely hear it. I like to look at something and then imagine what I’m looking at as making a sound. That’s cool.

It sounds like you’re on the verge of a creative explosion. I’d like to think so. I’ve just been trying to get all of the other things in my life kind of behind me so I can start feeling like I’m gonna stand at the starting gate again instead of struggling to get up to the line.

Some creative people seem to thrive on turmoil. Others shut down and can’t really create in the face of turmoil. I have friends that think I thrive on turmoil because they see me in it so much. It’s not true. I keep saying, “I’m not doing this on purpose.” I kind of need everything to be more in order for my head to be free. Otherwise, I’ve got too much going on…too much chaos.

That last bit about order and chaos hinted at some of the pressure that was plaguing Allan then. And it led him to some pretty dark places, usually fueled by copious amounts of Northern English cask ale. Stories abound. There are tales of Holdsworth running up bar tabs that ran into the thousands of dollars on tour or even at the 1020 Prime restaurant near his home in Vista, California, where he played a surprise set on April 10, 2017 to pay off his hefty bar tab (five days before he passed away).

I do recalling Allan quaffing a pint offstage over the years — at The Bottom Line, Iridium, even at Madison Square Garden, where he performed with guitarist Kurt Rosenwinkel at Eric Clapton’s Crossroads Festival in 2013.

But the only time I ever saw him helplessly drunk was at an afternoon workshop he gave at The Cutting Room in NYC on September 12, 2014. The place was packed with guitar nerds, all asking questions about technique, practice methods, inspiration and various ways of navigating around the fretboard. Allan demonstrated and spoke eloquently, addressing each query about chords and scales, tones and voicings as well as the intricacies of electronics and amplification. After an hour, there was a 15 minute break before a meet and greet, where Allan would sit at a table and sign photos for the assembled six-stringers. During that break, he disappeared into the basement of The Cutting Room and came back up roughly 15 minutes later, totally blitzed. So drunk so soon? How was this possible?!

I stood in line like the others, waiting patiently to get my signed publicity photo. And when I got to the table where Allan was seated, he looked up, immediately recognized me, stood up from his chair and came around the table to give me a smothering hug. In that brief moment he looked lost at sea, and I felt like a life preserver he was clinging to.

I interviewed Holdsworth on five occasions. Here’s an excerpt from a story that originally appeared in July 2000 issue of Jazz Times, entitled “Allan Holdsworth: One Man of Trane”:

Fifteen years have flown by since I first interviewed the revered, uncompromising virtuoso guitarist Allan Holdsworth. Back then he was completely puzzled about his place in the music industry. Among other things, he wondered why his music wasn’t being regarded at all by jazz radio stations. This irked him, especially considering the innocuous pap that dominated jazz radio at the time. As he put it:

“One of the problems that we’ve had over the past few years is that nobody can tell me what this music is. For example, a jazz radio station will be reluctant to play any tracks from any of my albums, which is a drag because they’re playing music that is, in my opinion, far less jazz than what we do. They play this funky processed stuff and these kind of easy-listening things, which to me have nothing to do with jazz. And conversely, the rock stations won’t play my music because they think it’s too jazzy. So we don’t get either, which kind of leaves me in this no-man’s land in the middle.”

Nevertheless, Holdsworth continued pursuing his rich musical vision through the ’80s and ’90s, periodically turning out product that was cherished by hordes of guitar aficionados and fellow guitarists around the world, while going virtually unnoticed by the jazz press and jazz radio — an egregious oversight.

Here was a guitarist who had attained the absolute pinnacle of what practically every plectorist I had ever interviewed was striving for — to liberate themselves from the percussive nature of the instrument by emulating the flowing legato lines of saxophone players. And Holdsworth had already accomplished this way back in the ‘70s with groups like Tony Williams Lifetime, Gong, Soft Machine, Bruford, Jean-Luc Ponty and U.K. He’s been refining that aesthetic ever since, coming closer than any other guitarist to capturing the spirit of John Coltrane on his instrument. Indeed, ‘Trane has been Holdsworth’s guiding light from the very beginning.

“He just kind of completely turned my life upside down,” Holdsworth says of Coltrane’s influence on him at the age of 18. “I remember when I first heard those Miles Davis records that had Cannonball Adderley and John Coltrane on them. It was fascinating to me. Coltrane’s playing in particular was a major revelation. I loved Cannonball also, but when I listened to him I could hear where it came from, I could hear the path that he had taken. But when I heard Coltrane, I couldn’t hear connections with anything else. It was almost like he had found a way to get to the truth somehow, to bypass all of the things that as an improviser you have to deal with. He seemed to be actually improvising and playing over the same material but in a very different way. That was the thing that really changed my life, just realizing that that was possible. I realized then that what I needed to do was to try and find a way to improvise over chord sequences without playing any bebop or without having it sound like it came from somewhere else. And it’s been an ongoing, everlasting quest.”

Ironically, Holdsworth never intended to play guitar at all. “I was just dabbling with it,” he recalls of his teenage years in the small town of Bradford in Yorkshire, England. “I had wanted a saxophone, I didn’t really want the guitar, but saxophones were pretty expensive in those days, relative to a cheap acoustic guitar. My uncle played guitar and when he had bought himself a new one he sold his old one to my father, who gave it to me. That’s basically how it started.”

His father, Sam, was a piano player who taught his son chords and scales. “But since he wasn’t a guitar player, he couldn’t tell me how it was supposed to be done on the guitar,” says Allan. “And I guess that’s how I developed such an unorthodox technique. I learned things from the piano and figured out on my own how to transpose those ideas onto the guitar. And I just acquired this dexterity through constant repetition and practice. I didn’t know it wasn’t supposed to be done that way, it just seemed perfectly logical to me.”

Holdsworth made a leap to warp speed after realizing that he didn’t have to pick every note. This became the basis for his incredibly liquid legato style. “One of the things I discovered early on was that if I played as many notes as possible on one string, I could get the kind of sustain that I was looking for. So I just practiced playing scales for hours and hours each day, playing four notes on each string until it flowed the way I was hearing it. And that completely opened up a new way of looking at the guitar for me. I would practice trying to play using a combination of left hand hammering-on and right hand picking in a way where I could try and make the notes that were hammered louder than the ones that were picked so that I could bury them in each other — so that you wouldn’t be able to tell which was which. And I just kept going with it until I got to a point where I tended to hear flurries of notes as a whole from beginning to end rather than hearing one note after the other.”

Guitar enthusiasts first became aware of Holdsworth’s revolutionary playing via early ’70s progressive rock bands like Tempest U.K., Soft Machine and Gong. His reputation carried over into the fusion camp through his mid-’70s recordings with drummer Bill Bruford (Feels Good to Me, One of a Kind), violinist Jean-Luc Ponty(Enigmatic Ocean, Individual Choice) and Tony Williams’ New Lifetime (Believe It, Million Dollar Legs). To the mainstream of rock and jazz audiences, he remains a little-known, unsung hero. To his admirers (which include such formidable guitar heroes as John McLaughlin, Carlos Santana, Eddie Van Halen, Neil Schon, Scott Henderson and Larry Coryell) he looms as a musical legend.

A cursory listen to any of Holdsworth’s 10 recordings since his 1979 debut as a leader, I.O.U., will reveal a guitarist of astonishing technique — the stunning linear concept, unparalleled harmonic sophistication, singular chordal voicings attained from seemingly impossible reaches on the fretboard along with his orchestral scope as an arranger and his uncanny improvisational daring. But on his latest release, The Sixteen Men of Tain, the reluctant guitar god has trumped himself. Fueled by the rhythm tandem of former Chick Corea drummer Gary Novak and in-demand L.A. upright bassist Dave Carpenter, Holdsworth has come up with his jazziest offering to date for the small, mail-order-only Gnarly Geezer Records (www.gnarlygeezer.com). The typically mind-boggling legato chops are very much intact on Tain. And given the swinging, interactive underpinning here, the connection to ‘Trane becomes all the more evident.

Just check out Holdsworth’s breathtaking abandon on “The Drums Were Yellow,” his stirring tribute to former comrade Tony Williams (whose signature was a yellow Gretsch kit). A kinetic, improvised duet with drummer Novak, this freewheeling piece reveals the true genius of Holdsworth’s sax-like conception. Astounding from the get-go, it only builds through the course of six minutes. The relentless flow of surging double-timed lines against Novak’s polyrhythmic pulsations — the guitaristic equivalent of circular breathing — escalates until Holdsworth is actually blowing “sheets of sound” on his instrument, à la ‘Trane. For guitarists of any level, it’s a simultaneously breathtaking and humbling experience to watch Holdsworth when he’s in that accelerated zone.

He erupts with similar six-string abandon throughout The Sixteen Men of Tain. Trumpeter Walt Fowler adds to the jazzy quality of this Holdsworth offering with tasty solo contributions on the evocative ECM-ish opener, “0274,” and the more turbulent “Texas.” But the real key to the inherently “jazzy” nature of this project is Novak’s lighter, more interactive touch on the kit. While in the past Holdsworth has aligned himself with such heavy hitters as Gary Husband and Chad Wackerman, either in combination with electric bassists Jimmy Johnson or Skuli Sverrisson, this more acoustic-sounding and inherently swinging rhythm section of Novak and Carpenter allows Holdsworth to deal at a different dynamic, and with no less spectacular results. Novak’s crisp but understated approach along with his hip time displacement sets a more intimate vibe for the surging title track.

More favoring the Roy Haynes school of elastic time feel and creative overplaying than a more blatant backbeat sensibility, Novak’s playing here brilliantly underscores yet another stellar example of Holdsworth’s signature chordal voicings and uncanny legato flow over complex moving harmonies. Holdsworth has never swung this hard.

“The interpretation of my original music can be played in so many different ways, almost like different kinds of styles,” he remarks. “And as I began playing with Gary Novak and Dave Carpenter a couple of years ago, I could hear that the interpretation of it was pushing into a different direction. And it sounded really kind of natural. So Ibasically wrote the material that was on this record with that in mind, because I knew that Gary Novak’s interpretation is a different kind of thing from the way that Gary Husband’s interpretation of it would be. He plays with a lot of energy but he can also play pretty soft, and I was enjoying that. [Novak] has a pretty amazing way of just making it feel good. It feels better than it does with other guys even though you can’t really put your finger on it.”

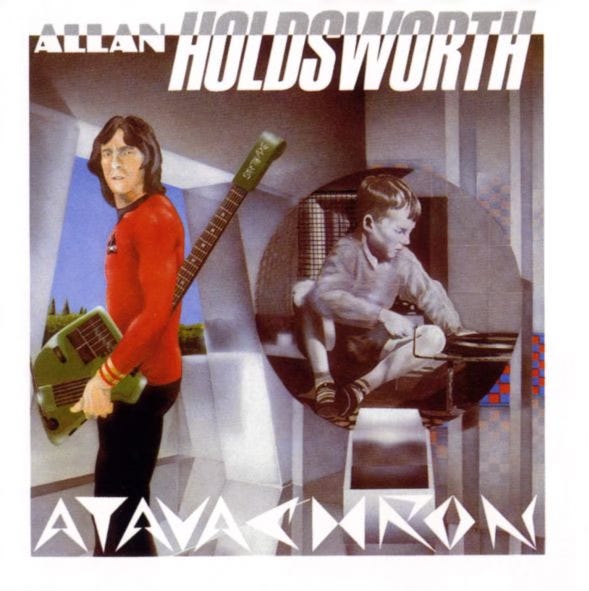

Elsewhere, Novak displays that softer, more interactive touch with his deft brushwork on the sublime Holdsworth ballad “Above and Below.” And he digs in more forcefully on “Eidolon,” a vehicle for Allan’s breath-controlled guitar synthesizer, the British-made SynthAxe, which is also featured on an orchestral-sounding reprise of “Above and Below.”

The SynthAxe was a particular favorite tool for Holdsworth through the ’80s in that it helped him get closer to the legato sax style that he had been emulating since hearing Coltrane recordings for the 7rst time back in the ’60s. “Because I always wanted to play a horn, which is a non-percussive instrument, the guitar is essentially a percussive and I try and make it sound like it’s not,” he explains. “But one of the things I always wanted to do was to be able to make a note and then change the whole shape of it after it sounded. You know, make it soft, make it loud, put vibrato on it, take it off, change the timbre of the sound, all after the note was played, which isnot a very easy thing to do with a percussive instrument. And with the SynthAxe I have that ability because I can hook it up to a breath controller and I can do exactly that. I can make a note and change it and shape it in a totally different way than I can do on the guitar. And because the guitar gave me the chords-which I would’ve surely missed if I would have played the horn and not the guitar-eventually it gave me the combination of being able to play like a chordal instrument and a horn at the same time, and that was very appealing to me. It gave me a lot of textural possibilities that I didn’t have with guitar. And I kind of got engrossed in it. But I don’t feel exactly the same way about it now. I think of it more as something that I can use for extra color.”

Holdsworth’s SynthAxe experiments were played out on 1987’s Sand and most profoundly on 1990’s Secrets. “That was, for me, the pinnacle of where I was getting with that instrument,” he says. “By the time I got to Secrets I think I was really finding my way with it in terms of trying to make it sound like it was me.”

He turns his attention back to the more conventional electric guitar on The Sixteen Men of Tain, the next step in a new direction Holdsworth alluded to on 1996’s None Too Soon, in which he put his legato stamp on John Coltrane’s “Countdown,” Django Reinhardt’s “Nuages,” Bill Evans’ “Very Early” and Joe Henderson’s “Inner Urge.”

“It is more of a jazz direction,” Holdsworth says of Tain, “but it’s staying sort of intact for me as well with the music. It has the original compositions but at the same time they were presented in more of a jazz form.

“I think it’s evolving constantly,” he says of his singular take on the six-stringed instrument. “I mean, I can hear it. I don’t feel like I’m forcing it anymore; it just seems to be natural. It’s becoming more organic. And I’m always learning, obviously. That’s an endless thing. It’s nice to know that you can never know. And once you get used to the idea, it’s really appealing-to know that I’ll never know anything. I like that, actually.”

I still have the ticket stub from the first show I saw him play. Wolf & Rissmiller's Country Club, Reseda California. Jeff Berlin was the opener.

I think about him in a group of two other players who had a presence in LA in the 70’s and 80’s: Lenny Breau and Ted Greene. Virtuosity wasn't enough. The music business is cruel that way.

There is a documentary to be made about guitar and LA in the late 70’s early 80’s. Valley Arts, GIT, the new guard of studio cats. Me and best friend used to see Jay Graydon bowling at Corbin Bowl. And you never knew who you would bump into in one of the many music stores along Ventura Blvd. Good memories.

"The Un-Merry-Go-Round,” might be my desert island Alan cut. As much as he loathed the idea of playing a blues cliche, this track has the depth and angst of blues. I get a similar feeling hearing, “After The Rain.” I think he'd be ok with that.

I discovered him after I discovered Kurt Rosenwinkel but I realized where a lot of Kurt’s and others’ synth prowess came from when I found Holdsworth. He died so young. Total freak. RIP.