The Trials and Triumphs of Bill Laswell

The bassist-producer turns 69 today, and is still healing at home

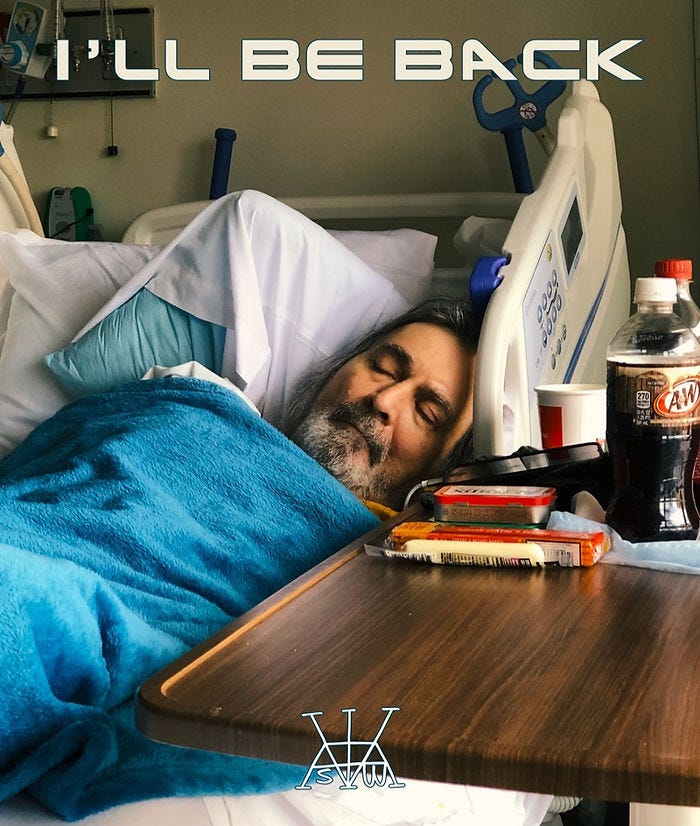

Today is Bill Laswell’s 69th birthday, though I don’t know how happy it can be for him, given that he’s in constant pain, can barely walk and has not played his bass guitar since being rushed to the emergency room in December of 2022 for a rare blood infection that has affected his heart. He remained in the hospital for three months and was finally out of I.C.U. (Intensive Care Unit) by April 1, 2023. He’s recuperating now at home in the Inwood section of Upper Manhattan. As his manager, Yoko Yamabe, posted today on his GoFundMe page (https://bit.ly/3HWrX7f), which has raised close to $100,000 to date to help out with his financial struggles in the midst of his health issues: “Bill is still struggling. Lot of pains and sometimes breathing problem. But he is here and trying to get better! He knows you are the reason that he is still here to celebrate another birthday. He is sending his big thank you!!” Previous Facebook and GoFund Me posts by Yoko documented his gradual decline.

August 30, 2022

“For the first time in a few months, Bill played the instrument today. He has been struggling with severe pains including back, feet, arm...but he got devastated when his fingers finally started to hurt. He wasn't sure if he'd ever been able to touch the bass. A few days ago, he got some medication. YES! He was able to play today at the rehearsal for Praxis concert in NYC. He will be performing tomorrow and the day after.”

September 9, 2022

"Bill Laswell was able to perform for two nights. He thought it was impossible to play because of the finger pain he's been suffering for a while. But again, he got medication and survived, more over got some new technique playing the 8-string bass with a pick."

January 20, 2023

“Bill was hospitalized in December 2022 with a severe blood infection on top of what he’s already been dealing with (diabetes and high blood pressure). This infection caused his heart to malfunction. After three rounds of electric shocks to set the heartbeat correct, he was rushed to the emergency room and was admitted to the ICU for an extended period of time. We were told that if we hadn’t called 911, he likely would have died. Bill doesn’t remember any of it. He is now out of the hospital, his infection is cured. However, he still has to be monitored and periodically examined. He started working again a couple of days ago while trying to recover at the same time. Bill had lost some recording projects due to hospitalization and has again fallen behind on the studio rent. He would need to come up with a couple of month’s rent as soon as possible in order to avoid an eviction process starting. At this moment, he really needs to keep the studio for work on some more recordings. Bill feels very bad asking again but really needs your help."

April 15, 2023

“Yesterday Bill stood up and walked for maybe five minutes or so. This was the first time he walked after being hospitalized. Physical therapists were surprised to see him walk…he does it with his strong will. Now we are waiting on the doctors at the hospital to check his wounds. He is still needing antibiotics and professional care but hopefully he could get out of there soon.”

July 11, 2023

“Physical therapist came today. Bill stood up and walk two steps with a walker, sat down on the wheelchair himself. He couldn’t do this before. We had to use a stool to slide from his couch to wheelchair, and it took a long time. But today, it was pretty easy! Maybe less than 30 second process. He had to rest for a while before standing up again — couldn’t breath well. But at least now he knows he can stand up, so it’s a big progress. Step by step, everyday small progress.”

July 15, 2023

“Bill stood up and walked about 2pm, with walker, then sat down in the wheelchair, then stood up again and walked back to his couch. It seems moving is much easier for him now. Step by step but improving. Nurse checked his wounds and said three wounds are all healed. There are 2 more to go. So, body is getting better, although he has constant finger and back pain. Hopefully, he could go and check these things out when he starts moving a little better.”

Sept. 17, 2023

“Bill’s pain is not getting better. He doesn’t think the medicine is working…pain in fingers, feet, back, shoulder. At this moment, we don’t know what is wrong. He is still not being able to move around. Will try to get another doctor visit. He still needs to be in bed. Hopefully things get better soon.”

October 20th, 2023

“Bill is sill not able to move well, most of the time staying in bed. He has pains in his fingers, legs and back. He got some medications but it’s not really helping at this moment. However, he is eating better and communicating much more. A couple of weeks ago, he played his bass for the first time after hospitalization. He got very tired but it was a positive experience for him. He is trying to get better. Hopefully soon.”

December 19th, 2023

“Bill is still not being able to move so much. It might be some nerve problem which we are trying to get some doctors to look at. It is not easy for him to walk so, he is still in bed most of the time. He is trying to work at home whenever possible.”

January 29th, 2024

“It’s not been a good New Year so far for Bill. He’s been sick. Besides his usual health condition, he has been in bed most of January. We thought he had to go to the hospital again, but he is better now. He still cannot walk, though he is trying little by little. He is also trying to start some new music projects, hoping things will get better.”

Clearly, it’s been a long and painful road to recovery for the visionary bassist-composer-producer, who first came to prominence in the 1980s and continued to be a potent force in music for the next three decades. And yet, his resilient spirit remains strong. Though managing to operate largely out of view of the mainstream, Laswell has collaborated with the giants in practically every genre of music, from Miles Davis to Mick Jagger, Bob Marley to Bootsy Collins, Henry Threadgill to Laurie Anderson, Tabla Beat Science, Sly & Robbie, Matisyahu, Bernie Worrell, Maceo Parker, George Clinton, Pharoah Sanders, Gil Scott-Heron, Lee “Scratch” Perry, Africa Bambaataa, Manu Dibango, The Last Poets, Buckethead, Ronald Shannon Jackson, Ryuichi Sakamoto, James Blood Ulmer, Blind Idiot God, Swans, Ginger Baker, Iggy Pop, Sonny Sharrock, Motörhead, Yoko Ono…the list goes on and on.

Laswell’s underground sensibilities first collided with commercial success when he produced the Grammy-award-nominated “Rock It” for Herbie Hancock in 1983, a gargantuan hit that helped hip-hop crossover to the mainstream. As a player, he has collaborated frequently with John Zorn, whether it was duets or the power trio Painkiller they had with Napalm Death drummer Mick Harris. Other commercial successes included Mick Jagger’s 1985 album, She’s the Boss, The Ramones’ 1990 album, Brain Drain, and the Buddy Miles Express’ 1995 album, Hell and Back.

I first became acquainted with Laswell’s bass playing from a record listening session in February of 1982 held in the offices of the newly established Elektra/Musician label headed up by former Columbia Records president Bruce Lundvall. One of the albums being introduced that evening in the first batch Elektra/Musician releases was Material’s Memory Serves, a punk-edged No Wave outing centered around Laswell on bass, Michael Beinhorn on synthesizers and tapes and Fred Maher on drums and featuring a cast of avant guests including trombonist George Lewis, alto saxophonist Henry Threadgill, violinist Billy Bang, cornetist Olu Dara and guitarists Fred Frith and Sonny Sharrock. I think I may have first seen Laswell play live later that year in one of Derek Bailey’s Company performances at Roulette in Tribeca on Dec. 16, 1982. As I recall, alto saxophonist John Zorn, regenade British guitarist Fred Frifth (from Henry Cow and the Art Bears), German avant garde saxophonist Peter Brotzman (he of the blowtorch intensity) and French upright bassist Joelle Leandre were also on the bill for this improvising workshop organized by esteemed avant garde icon Bailey. I subsequently saw Laswell perform at Maxwell’s in Hoboken (or was it at Hurrah’s on the Upper West Side of Manhattan?) with Curlew, saxophonist George Cartwright’s group edgy punk-funk group, and in different situations at various other gigs around town. From those early years on, I witnessed Laswell in a variety of settings, from a gig by The Golden Palominos (Zorn, Frith, Arto Lindsay, Jamaaladeen Tacuma and David Moss) at Irving Plaza to later appearances with Painkiller, the superband Last Exit (Peter Brotzman, Sonny Sharrock, Ronald Shanon Jackson) and his band Praxis (featuring guitarist Buckethead) and his ambient dub project Divination.

I had initially interviewed Laswell for a Downbeat piece in 1983, then subsequently interviewed him for MIX magazine in 1985, Bass Player in 1991 and maybe half a dozen others after that for magazines in the States, Japan and Italy. The following is from an interview I conducted with Laswell in early January, 2018 over lunch at the Landmark Tavern, a historic Irish pub on 11th Avenue and 46th Street on the far west side of Manhattan. In this excerpt we focused primarily on the early days, including his work with David Byrne and Brian Eno on 1981’s My Life in the Bush of Ghosts and his bands Massacre and Deadline, leading up to the formation of his Axiom Records. And that’s just scratching the surface of Laswell’s incredible output. We could’ve talked for days just documenting everything that he’s done.

Talk about that period when “Rock-It” became such a big hit for Herbie Hancock in 1983.

Yeah, that was definitely a financial and commercial success. And that one piece probably drives most of what I did with Herbie, who I’m still in touch with and from time to time do things with. And that one piece kind of elevated both us to a different place. And from there we started experimenting even more and doing more things, but that one piece was the key to opening the whole thing. Herbie was on Columbia at the time and I think he hadn’t been selling a lot of records. So the success with “Rock-It” came out of nowhere. No one knew what it was. There were a few people at Columbia at the time…they took a risk with it and they made an expensive video and then they got behind the record when they got basic responses from certain people that were hipper than the A&R people. And even Herbie wasn’t sure. He didn’t know what this really was, nor did we. We just thought we had done something extremely experimental with a great jazz piano player. But there’s a few things that happened that really woke us up as well.

It’s cool that Herbie was open-minded enough to even deal with this experimental music at the time.

He’s always been open-minded, and this hit him out of nowhere and there was no way he was ready for it. But he remained open-minded throughout, and that paid off for everybody in many ways.

I had heard that some of the tracks for Future Shock, the album that “Rock-It” appeared on, were initially intended for your group Material.

No, not for Future Shock. There’s a lot of records where tracks were intended for someone and they went to someone else. There’s a lot of that. But not Future Shock. That was done two songs at a time. We’d do them in New York and then take them out to Herbie in California, come back to New York to mix them.

What was your relationship with Michael Beinhorn at the time? Were you guys partners?

Well, Michael Beinhorn was there when we started Material. There were a few others that came in and out but when it came down to Herbie’s project, Michael Beinhorn was still there. He didn’t do a lot, though. He wasn’t a playing musician. He could deal with sound effects. He wasn’t really a keyboard player, he uses the synthesizer as a sound generator. And later on he got a little better at programming on different sequencers and machines. But he wasn’t really a musician. So I have to take credit for a majority of that piece. And bringing in the turntable, obviously, was my thing as well. The whole concept for the tune, really.

What things were in the air musically around that time — ’80 to ’82 — that came to fruition with this Herbie project. There was a lot of stuff happening, some of it was getting documented, some was not. But you must’ve had your ear to the ground…and just the energy that was happening in New York at the time…were you keyed into it?

Well, what happened was, I worked with a guy called Roger Trilling. Roger was the guy who was always snooping around, trying to find out who was in town and what’s hip and what’s the new thing. He’s still kind of like that. Anyway, Roger was kind of making the rounds and he ran into a guy named Tony Meilandt, who worked for David Rubinson, Herbie Hancock’s longtime manager. And he was determined to get Herbie into an environment where it was much hipper than just fusion or some kind of ballads or whatever Herbie’s last few things were. Tony was really interested in Brian Eno and all that ambient stuff like that, and he realized that I had been working with Eno, which was a big thing for him. And I’m pretty sure they tried to contact Eno to work with Herbie…I don’t think Eno would’ve responded to that. Anyway, Roger told Tony he works for me, so then Tony wanted to talk me. And right off the bat he said, “Do you want to do two songs for Herbie?” It just happened right there at our first meeting. And I didn’t see it as a really big deal. I didn’t think we were going to make a hit. I just assumed it would be something experimental and really interesting and so I told him, “Great idea, let’s do it.” And so I started getting a concept together.

At that moment, hip-hop had kind of moved from the Bronx to downtown. And The Roxy was open, which was on 18th Street on the West Side. We would go there every night and it was a DJ kind of scene. So Tony Meilandt brought Herbie to New York and we met in the VIP Room at The Roxy to check out this scene. And the DJs were changing all the time — Red Alert, Africa Islam, DST, Grand Wizard Theodore and on and on. Afrika Baambaataa was kind of running the whole thing. So this emergence of this hip-hop scene with turntables, I was kind of fixated on that. So I said, “Well, if we’re going to do instrumental music with Herbie, I’m going to lean pretty hard on this kind of hip-hop thing.” I wouldn’t say rap, but it was definitely DJ culture. But Herbie didn’t really get it. He didn’t know what they were doing. I remember him saying, “It sounds like there’s a riot going on downstairs.” Anyway, I agreed on these two songs and I wanted to use a turntable as kind of the lead instrument, or at least the break rhythm instrument. So I said, “I don’t know exactly who to use. Who can play in time?” I knew Grandmaster Flash was a well-known DJ but he didn’t play in time very well. And so I called Bambaataa and said, “Who’s a DJ who can play really well in time, like a drummer?” And he said, “You need to get Whiz Kid,” and he gave me the number. So I called Whiz Kid and said, “I’m doing this project with Herbie Hancock and I want to use a turntable as a rhythm instrument and he said, “Yeah, I’d love to do it, but I just joined the Army. But I can refer you to my protege. His name is DJ Cheese.” And I thought, “I can’t go to L.A. and Hollywood and say, “OK, this is it — DJ Cheese!” So I called Bambaataa back and explained the situation. Cheese turned out to be a great DJ, and later on in time I realized that. So then Bambaataa said, “Why don’t you get DST? He plays everywhere and he’s got a following and people like what he does.”

So I called DST and said, “Come to the studio.” We were in Brooklyn. He came to the studio with a car service…a Puerto Rican guy who came with him in the studio and waited for him while we cut the records. And I gave DST some weird records from Nonesuch to work with on the turntables, like Gamelan music and all kinds of exotic stuff. And he used them. He played on two pieces and the session lasted probably an hour, maximum. So then I paid his driver and I remember paying DST $350. And I think the driver got almost as much. But he put that stuff on the tape. And once we had that on, then I knew we had something. And step by step we overdubbed on top of what he did — Daniel Ponce played Afro-Cuban percussion on top of it, then I played the bass. Everything is a hybrid. Everything comes from somewhere. Bambaataa brought that out with “Planet Rock,” where he used Kraftwerk and all this kind of rigid machine music from Germany, and I was conscious of that. And I realized this is probably not going to appeal to people who liked funk and soul music but it’s different. So I just went for the German thing. And my references for Herbie were his earlier records, and maybe also Manu Dibango. At the time, there was a little bit of electronic music starting to come out of Detroit and I listened to that, and they were all over the German stuff too. And then in New York you had Mantronix, which was influenced by the Euro electronic music. So the tracks that we made was a hybrid of all these things.

So we went to L.A. and Herbie played on top of this. It took no time at all. And I gave him a lot of references and he stuck to them pretty much. We mixed it in like an hour and a half, I remember, at El Dorado, which was an old studio in L.A. The engineer was Dave Jerden, who had spent a lot of time with Frank Zappa and was also working with Eno as well. So we had that in common. Anyway, we brought the tapes back to New York and called Tony Meilandt and he said, “People love it! Let’s do a whole album!” And that’s how that happened. But we didn’t really know when we left that studio in L.A. what we had. And we didn’t expect much to come out of it. When we realized it was hit came later. We were on the road…it was DST, myself and Grandmaster Cab from Coldcrush Brothers. We were driving to a gig and we were early so I said, “Let’s stop at one of these stores that sells speakers.” We were just starting to make a little money, like maybe enough to buy speakers. So we went into this big speaker store that had everything and we told the guy, “We want to hear some different speakers.” We were thinking about studio monitors or just at-home speakers. And this guy had a tape that he started to play on different demo systems…I think the tape was a Kansas tape or something. So we went to the guy and said, “No, no, no, man! We don’t listen to stuff like that. Here, play this.” And I gave him a cassette copy of “Rock-It” before mastering. And he put it in and played it and it sounded so good that this kind of weird chill came over everybody. And when we turned around there were like 20 kids standing there, just entranced by this music. This is like the beginning of what would later become hip-hop and they were like, “What the hell is that?” And DST looked at me and said, “Shit! We got a hit!” Because kids get it immediately. And so before we even got on the plane to return to New York we had realized we have this thing. And not long after that…I remember the week that it came out it was everywhere. That’s all you heard. We later took a trip…we drove from New York to Florida just for the purpose of going to record stores along the way. Because there used to be crazy record shops in those days and we were buying vinyl at every place. So it was me, DST, Bernard Zekry, who later became a huge tv journalist in France, and Kerakos (Jean Georgakarakos), who ran Celluloid Records. And we went buying records up and down the East Coast, and at every store we encountered, “Rock-It” was playing. And we’d say, “Yeah, we did that!” And everybody was like, “Yeah, right!” Nobody believed it. But it was playing everywhere. Then we realized it was a kind of big thing.

So that initial session you did was just the two songs?

Yeah, the ones that I took to L.A. that I mixed with Dave Jerden — one is called “Earth Beat,” the other was “Rock-It.” And we really mixed them in a way that we were doing a rough. There’s not a lot of stuff on tape. It’s pretty stripped down.

And you say that DST was dealing with some fairly exotic records on his turntable?

Yeah, because I gave it to him. Otherwise, he was doing what everybody was doing, which was “Good Times,” “Fab Five Freddy,” “Change the Beat,” just basically stuff that was good and fresh…that’s all they did. And I told him, “You know, you can take this somewhere else. Here’s the Ramayana Monkey Chant from the Gamelan Orchestra album from Indonesia. So he heard that and he’s using it not on “Rock-It” but on the other song, “Earth Beat.” And at that point, that’s when we started buying tons of weird vinyl. I gave him a ton of Stockhausen records and all these crazy electronic composers, because they had a lot of interesting noises on them.

You mentioned earlier that you were looking for a turntables who had good time. What else were you looking for in a turntablist?

It was about time because we were dealing with machines that were supplying the rhythm, so you couldn’t be sloppy on top of that. You had to lock into that. And nobody was doing a lot of looping then and there were not any samplers that could do more than just a couple of seconds on. So whoever was going to play that turntable had to play like a percussionist or a drummer. I knew that I needed that. And I didn’t know that DST could really do that, but he did. And it turns out he was better than everybody else, and I heard that. Because I worked with everybody dealing with turntables, starting then and pretty much right up to now. So he did cover the rhythm parts really well.

I remember going to The Roxy and I also saw Grandmaster Flash & The Furious Five do “The Message” and the Peppermint Lounge’s second location after it moved from Times Square.

Right. There were a lot of clubs and those clubs started to bring in some of the hip-hop stuff. Not a lot. But Grandmaster Flash was getting his name out there. He had those few songs that made them pretty famous. “Message” was a bit hit so they had the names and they started to get into those clubs. There was Hurrah, Danceteria, CBGB was active. There were probably five clubs you could play on the weekend. In those days, which was early ‘80s, I would probably play two or three times each weekend at a different club with a different band. Even back then that was a lot of different options for bands put together.

So “The Message” and “Planet Rock” came out shortly before “Rock-It”?

Shortly before. Not much before.

And those three records really captured a moment in time that was the sound of New York street life.

At that moment, yeah.

Prior to that, did you go to the Bronx? Did you see DJ Kool Herc and those cats at the street parties? Were you checking that out before it got documented on records?

Yeah, Cool Herc to this day has never made a record. But he was a DJ and he worked at a place called Disco Fever. There were a couple of other names that I’m forgetting but he was like the first guy. He started all that stuff in Mt. Morris Park and some of the bigger parks in the Bronx. He comes from West Indies…kind of a Jamaican background. And he was familiar with what Jamaicans do, which is put the sound system on a flatbed truck. He’s the one that started isolating breaks and breakbeats. And he would just play beats all the time with a massive sound system. I knew him. To this day he’s still struggling all the time, but he’s still around. Bambaataa was a selector. He was not a scratch DJ, he was not an entertainment DJ. He just had this crazy idea about selections. So he would play in the Bronx River Armory, which was full of 2,000 kids or something, and he would play Rolling Stones, and everybody’s confused. But he keeps playing stuff until everybody gets into it. So he was important. I saw him not too long ago. Mellie Mel was also great then, and he’s still great. But it’s another time, you know?

That scene you described of 2,000 kids hanging out, listening to Bambaataa…that must’ve been amazing.

Yeah, I played there once. I had Ampeg amps — two heads, four cabinets. And I hooked it up through…I can’t remember. But I just played along with the records that Bambaataa would select. I think we played Jimmy Castor Bunch…there was one song…I think we must’ve played that for like a half hour.

So you were trying to capture some of that energy on “Rock-It” while putting your own creative spin on it.

Yeah, it was so quick the way everything happened. Tony Meilandt was quick anyway, thanks to the cocaine. “OK, let’s do this! We’re going to mix tomorrow!” He just wanted to do stuff. So I recorded stuff here in Brooklyn…pretty much everything but the keyboard. And then we went to Herbie’s garage studio on Doheny Drive in L.A. And I don’t think Herbie played for more than an hour. And he didn’t really know what he was doing with it, and no one else around him did either. It was a little tough. Because we were like, “Yeah, this is what we got,” and everybody’s scratching their head. And we didn’t really know ourselves until we went to that speaker store.

How much time lapsed between that moment when DST shows up in the car service and you guys are in Herbie’s studio?

A week or two. Less than two, probably.

Was Herbie dealing with the Fairlight digital synthesizer at that time?

Not at that moment. I think what happened was he got a Fairlight endorsement but it didn’t arrive in time to use it on that record. But when the record came out he wanted to say thanks to Fairlight on it. So I think the Fairlight is actually not on it. He just did that to encourage them and get it at half price. I ended up buying that Fairlight from him at a time when Fairlights were still expensive. I bought two. But I remember when I got rid of it, it was not worth anything. So I ended up giving it to some guy just to move it.

So that is not a valid piece of technology anymore?

No, not even then. It came and went. It got knocked out of the box by…

The Synclavier?

Yeah, which was super-expensive at the time.

Interesting how quickly technology shifts around.

It’s always been like that.

I remember a couple of albums that Herbie did leading up to Future Shock were pretty lame. He did a disco album in ’78 called Feets Can’t Fail Me Now. It was not good.

No it wasn’t, but he had that period before that where he was doing stuff that was really interesting — Mwandishi (1971), Crossings (1972) and Sextet (1973).

Didn’t Crossings and Sextet feature Patrick Gleeson on synthesizers?

Yeah, Patrick Gleeson is what made those records unusual. On Sextent there’s a lot of Patrick. That was a great record. Probably didn’t sell anything, but it was a great record. Great cover. And Patrick Gleeson is all over that. Then Herbie did Head Hunters, which was great. And there’s another one that’s not bad, Thrust. And then they did the live in Japan album, Flood. That one was pretty good. So he had that moment there. And this was all coming from out of nowhere. He went from jazz stuff on Blue Note and then he had Head Hunters, which was a major hit. Herbie has this thing where about every ten years he has a hit song. So he has “Maiden Voyage” in 1965, then he had “Chameleon” in 1973 and then “Future Shock” in 1983. So there’s always been this gap of ten years. He’s overdue now but he might still do another one. You never know.

Well, that’s hip of him, or his manager, to realize he needed to get in touch with something that was happening now when you guys got together.

Well, his manager was David Rubinson didn’t have a clue. He’s probably responsible for some really bad decisions and bad ideas, but Tony Meilandt, who worked for Robinson…Tony was the one. And I did a lot of stuff with Tony after that. He had a serious drug issue, which he didn’t have that bad when we started with Herbie. But it just increased and he kind of disappeared into the various high-end rehabs which didn’t work. He came back and he started making sense and he helped me with some management things in L.A. So Tony was on the upswing, he was on the comeback, but he couldn’t leave the drugs alone, so he OD’d about 15 years ago.

Was he like a West Coast counterpart to Roger Trilling?

No because Roger didn’t understand business so much. Roger was like a guy…he wanted to know all the cool musicians…he was managing James Blood Ulmer and I think he was driving Blood crazy. He wasn’t really a business guy and he never really dealt with lawyers. But Tony Meilandt was actually learning about business and he was getting into it. And eventually, because of the success of Future Shock, Tony eventually replaced David Rubinson as Herbie’s manager and things were kind of moving along. Tony had a lot of connections in Japan. He worked a lot with Tony Williams and Wayne Shorter, then later on he started doing more commercial stuff. But he pretty much was with me whenever he could and he helped me with a lot of things. But he was a beast when it came to drugs.

I’m interested in your participation in the 1981 David Byrne-Briano Eno recording, My Life in the Bush of Ghosts. What did you get from those sessions that may have stuck with you and maybe influenced your work on other projects you did.

Bush of Ghosts, for me, was eye-opening. It was a huge influence because I saw how Eno was approaching being in the studio and dealing with equipment. I spent a whole summer with him just recording weird ambient stuff, and we would go to Canal Street and buy junk that might generate different sounds that we would process. Bush of Ghosts…it’s a weird story because when I met him and David Byrne, they were like, “We really want to make a very European record.” And they were talking about stuff like the seminal krautrock band Neu! with Klaus Dinger and those guys…almost like disco beats. But then they play this very minimal ambiance on top of it. So that’s really what they were focused on. We went into RPM Studio to record that album and I remember the night before that session I played at CBGB’s in a band with Ornette’s son, Denardo Coleman, on drums. And after that gig I put my Fender Precision bass in the back of a truck that one of the musicians was driving, and somebody in the East Village grabbed that bass. They stole it! So I didn’t have an instrument for that Eno session, so I immediately called this guy I knew who lived in the Bronx and I said, “My bass just got stolen and I have this session tomorrow which is kind of important. Do you have any basses?” And he said, “Yeah, I can bring you something.” So he came to RPM, opened the case and unveiled the cheapest bass I had ever seen. And it had a big DEVO sticker on the front, which was really embarrassing. And I kept telling everybody, “This is not my bass. My bass got stolen. I don’t like Devo.” And there was a girl on this session named Edwina, who played congas in Washington Square Park. I used to walk through that park with Eno and that’s where Larajii got discovered. I told Eno, “You gotta listen to this guy.” So we checked him out in the park and then Eno gave Larajii his phone number. And not long after that meeting Larajii made a record on Eno’s label called Day of Radiance. So Edwina sat down and she only knew how to play one thing, which is what she played in the park. So I just immediately started playing with her and at that moment that record took a different direction and then everybody kind of went with that direction. But it really comes from that girl. I wouldn’t have thought of doing that. Basically, she’s just playing like a breakbeat on congas. So then My Life in the Bush of Ghosts really became this more African thing…and Eno got really into Fela after that. So everything started to get very African then. So ironically, Eno and Byrne went from, “We want to make a very European record,” to this more more Afro-centric kind of thing with park rhythms and break beats, almost overnight. I remember not long after that record came out, I went to Irving Plaza to see James Brown, and Eno and David Byrne were there. And they were wearing all black— pants, shoes, shirt, everything was black. They were really into James Brown. Mind you, these are the guys who wanted to make a European record. So I said to them, “Wow, you guys are definitely moving along. I can just imagine in 20 years you’ll probably be listening to Duke Ellington.”

After playing on My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, you played on Eno’s 1982 album, On Land.

I wouldn’t call it playing. That’s around the time we were buying junk and making noise, processing it. And there was a guy called Axel, who was from that whole German school of Can and those experimental rock bands. So we really just made noises and stuff. And then I had a friend from Chile who was a photographer who had made these field recordings in Honduras of these frogs…a pretty good recording. So he brought it back and he gave it to Eno. Those frogs are on that record, On Land.

I remember Robert Quine saying that he had played on some tracks for On Land but didn’t hear anything he played on the final album. Everything got processed and manipulated so much that it wasn’t his playing anymore.

Yeah, I’m pretty sure I introduced Quine to Eno. And then Quine brought him a lot of Miles records like Get Up With It. And that completely blew Eno out, so then all of a sudden he was into that. And so he went from, “Let’s make a European record,” to Fela Afro-beat to all this other ambient shit. And how Eno got into ambient music — he was laid up in the hospital listening to that Miles album, Get Up with It, over and over again, specifically one piece called “He Loved Him Madly,” which took up a whole side of the album and was his tribute to Duke Ellington, who had recently passed. And that track really inspired his albums like Music for Airports and On Land.

What’s the story behind that Deadline record you put out in 1985, Down By Law, which has Jaco Pastorius and Paul Butterfield playing on one track, "Makossa Rock"?

Yeah, Jaco’s on it a little. The connection is that Phillip Wilson, who played in the Butterfield Blues Band. Phillip played on a couple of classic records by the Butterfield Blues Band and he even appeared with them a Woodstock. And Phillip was playing drums on Down By Law. This was around the time when Jaco was doing that shit then where he’d run on stage at the Lone Star and jam with whoever was playing there. So Paul Butterfield was playing there one night and, of course, Jaco ran onstage to play with him. I went down to the Lone Star with Phillip to see Phillip, so after they’re set we said, “You guys wanna come just around the corner, we’re doing a session. We can get some cash for you.” So Jaco came by, and he was out of it but he did his thing. And Butterfield, the same. We gave them probably not much money…whatever we had. But that was one of those times where you just grab somebody out of the club…they were both pretty much out of it at the time.

Jumping back to “Rock-It,” did you employ any sampling on that track?

There wasn’t really anything like sampling at that time. There was a Lexicon box that you could sample like one or two seconds. We did everyone for “Rock-It” at our studio in Brooklyn but I remember I went to RPM Studios in Manhattan to try and catch some samples of things there. I remember trying to get this snare sound from a Led Zeppelin record that had come out then called Coda. And there’s this piece on that album called “Bono’s Montreux” where it’s only drums, and I wanted to get that sound. So I was trying to grab just one or two seconds of this snare sound from that track, and the sampler grabbed just a bit of a guitar chord. So when you hear “Rock-It” you’re going to hear a heavy metal guitar chop that happens on one…it’s like this blurt of sound. And that was total accident. That came from letting the record play and then hitting the sampler right when that chord came in.

Wow. I remember that. I always thought it was a live guitarist in the studio.

No, it’s Jimmy Page. Nobody knows that. But later on I heard a lot of people copy that idea — putting that guitar hit on the one of a section.

So in a way, the technology for “Rock-It” was fairly primitive at that time.

It was very primitive. Rhe drum machine was a DMX Oberheim. And I didn’t know how to program it but I had an idea about a beat and a fill. The fill was going to be this staccato thing that the turntable was going to play with the drum. And I didn’t know how to program it but I knew how to switch from program to program. So instead of just making a piece programmed, I would just count the bars and then on the one I would hit the next part. And I did that for the whole song. That’s how we printed it. Because I didn’t know how to program the thing. I knew how to make the beats and store them and then you have maybe four or five different sections so I had to switch manually because I didn’t know how to put the piece together.

That’s some intuitive production work right there.

Yeah, there’s a lot of little things in that song. I would say to Herbie, “Just say on the vocoder, “Rock-It, Don’t stop.” And he said, “We can’t say that. You just played me a record that says that.” I said, “Don’t worry about it, nobody’s gonna know.” So that’s why it’s called “Rock-It,” because of that reference.

Are there any other clever usages of technology in the studio from that project where you’re making due with what you had?

Like I said, there wasn’t a lot that we could do. The Prophet V had a sequencer that you could make sequences with ,but I don’t think we ever really used it. Because nobody knew how to really use it well. In those times, you had to really learn the machine. That’s what I liked about Eno is that he really didn’t know anything about programming. He would go buy a drum machine and just turn it on and press a button….just to see what happens. He didn’t take the time to even read the manual.

There was a story about the Beatles engineer Geoff Emerick, where John Lennon had said to him, “I want my vocals to sound like I’m on top of a mountain shouting,” before they recorded “Tomorrow Never Knows” on Revolver. And he’d have to make it happen, intuitively, just by using whatever he had in the studio.

Yeah. And George Martin was kind of deep too. He was really into Stockhausen and all this kind of music. He started out by doing tv commercials and cartoon music. I spent a lot of time with him in the early ‘80s after Herbie. Definitely a character.

After “Rock-It” came out, it was a hit almost immediately?

Yeah, it was, and I don’t know how they did that. But somebody spent some money trying to make back the money that they had lost over all the bullshit that Herbie had been doing. You know, because I think he was in the hole pretty heavy by that point. And this song brought him back. It brought him up to speed. And yeah, they put money in, they did this video with Godley & Creme, which was I think the first time black people were on MTV. But Herbie was hardly in it. It was mostly robots. I think DST might be in it a little bit too. But they paid for that and they must’ve done massive promotion, because “Rock-It” was everywhere. It was big in Japan, Indonesia, Thailand, all over Europe, of course.

Did you go out on tour with Herbie after “Rock-It” hit so big?

No, we talked about it but I couldn’t do it. I was starting to get too many offers to produce other records. From “Rock-It,” I was starting to get tons of work. And I thought it was better for me to move on and do more things and not get stuck with this same sound. That’s what happened to DST. He just stuck with “Rock-It,” and he’s still stuck with “Rock-It” today. I didn’t want to get into that whole thing. I wanted to continue working with Herbie, but on new stuff. So I kind of couldn’t afford to do it because they weren’t paying that much.

So how quickly did offers start coming in to do projects with other artists.

Really quickly, maybe a matter of weeks. Mick Jagger called me because he had heard this song I did with Yellowman called “Strongly Strong,” which was a huge hit in the Caribbean. Mick had this getaway place down there and that’s all they were playing. And he had no idea that song was done in Brookyn. He thought it was done in Jamaica or something. So he contacted me because of that song. And I had also worked on Laurie Anderson’s Mr. Heartbreak, and for Jagger that was like an art credibility thing. So if you mix together a hit record in the Caribbean with this art background and “Rock-It,” which was this hit of electronic music…that got Mick’s attention. And at that time, the biggest producer on the scene was probably Nile Rodgers, but everything he did kind of sounded the same. So I started getting these called because my stuff was different. I got called to do the Rolling Stones but I realized it was going to be like two years of craziness in Paris, so I kind of bailed on that one. Then Yoko Ono had called that same week, and her budget was better than theirs.

Shortly after Yoko’s album, Starpeace, came Jagger’s She’s the Boss. What else came in after this newfound profile you garnered from the success of “Rock-It.”

After Mick and Yoko came albums with Iggy Pop, Swans, The Ramones, Public Image Ltd., which was probably the most significant of the outside projects I did. Around ’84 I met George Clinton and Bootsy Collins and all those guys, and there was a lot of projects that we did from that connection. And I would bring those guys onto other records too. And then in ’86 came Last Exit, our band with Sonny Sharrock, Peter Brotzman and Ronald Shannon Jackson. We toured a lot and up until 1989. And that’s when Chris Blackwell sold Island Records to Polygram UK for big bucks. So that’s when I went to him to start Axiom Records, which happened like in one meeting.

Tell me about your period with Axiom Records, which was from 1989 to 1999.

That involved a lot of work in Africa, India and Asia. There’s so many things, so many areas, so many experiences. And some of the things people don’t know about. There’s major things that happened and there’s a lot of recordings. And some of them were unusual…like, ground-breaking records. Not all of them, obviously, avant garde. There’s records that sold millions of copies on occasion. So it’s a little different. It’s a pretty diverse spectrum. And there’s heavy people involved, from master musicians to hip-hop to whatever. It’s crazy! Weird things that come out of left field, and certain things changed people’s lives. I don’t often say that to people and I don’t hear it said about other things so much, but when you reach out to these things that are so unusual and diverse and probably wouldn’t have happened if you hadn’t taken some chances…and you know, we plowed through quite a bit of money in those days, thanks to certain record people and investors. It wasn’t always small money. I was doing field recordings for the kind of money people were doing commercial music for.

So what you did was sort of like the Alan Lomax field recordings, where he took his mobile recording unit to the places where the music was being produced.

Yeah, he did important stuff. Again, it’s really a long time ago so the sound quality is very different. Because we had a budget, we were able to take pretty expensive gear…some of it we owned and some of it we rented. But we pretty much never went on a field recording or a special session like that without really good equipment, and it made a huge difference. That’s why the Axiom thing was a statement, because it’s not just the raw field recording. There’s many labels and many releases that are badly recorded, including Alan Lomax, because the technology was not there at that time. He got the right stuff and he really tried, I think, to do things. There’s a couple of those guys. But this is a little different. It’s catching up with the technology on a lot of this stuff.

Yeah, you could say that Dean Benedetti, who traveled around recording Charlie Parker solos…the quality is very shitty but for Bird completists, he was performing an important function. They were essentially field recordings but the field was 52nd Street.

Right. Those guys, back in those days usually it was Nagra recorder, which are good machines, if you have really good mics. If you get a stereo two mic setup with that machine you can do some decent recording. But it’s all a matter of taste and positioning and knowing what you are doing. And I don’t know if a lot of those guys are engineers, really.

Hello, I vaguely remember reading this article probably when you first posted it. I wasn’t familiar with you, your writing then. Since then I have come to be familiar with your writings. Maybe about a week ago I posted an off topic reply to a post of yours asking about Bill Laswell. I am an old friend of his. I played with him in the first band he was ever in. But we were friends beyond that. I became a chef with music a hobby. When Bill was first getting with Eno I was living and working in The Hotel Mayflower at Columbus Circle. We would see each other then. Caught up with him a time or two since. I learned of his illness and have checked on him through the “Go Fund Me Page”. I got a wave of dark feeling recently and worried about him. It seems he’s still struggling but with us. I am thankful. He was a friend who will always be my friend.

Anyway, I have been reading you for awhile and do really enjoy your writing. So I decided to subscribe to your site. I also follow some other great writers like yourself, Bret, Alki, Su, and Jovino. I know I can be a bit wordy, I apologize in advance.