The Free Spirits and the Birth of Fusion

Tracing the roots of the jazz-rock movement back to the pivotal year of 1966

I am a child of the fusion era, going back to a time when they still called it jazz-rock. I recognized the clarion call of Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew and A Tribute to Jack Johnson while also acknowledging the impact of seminal jazz-rock/rock-jazz albums like Tony Williams Lifetime’s Emergency!, Frank Zappa’s Hot Rats and, of course, Jimi Hendrix’s Are You Experienced, which I had always regarded as the Big Bang that launched the whole fusion movement.

In the early ‘70s, I soaked up the Mahavishnu Orchestra’s The Inner Mounting Flame and Birds of Fire, Weather Report’s I Sing the Body Electric, Sweetnighter and Mysterious Traveller, Return To Forever’s Hymn of the Seventh Galaxy and Where Have I Known You Before, Herbie Hancock’s Head Hunters and Thrust, Larry Coryell’s Spaces and Introducing the Eleventh House. Hell, I was even digging on Klaus Doldinger’s Passport.

By the mid ‘70s it was RTF’s No Mystery and Romantic Warrior, Mahavishnu’s Visions of the Emerald Beyond and Inner Worlds Weather Report’s Black Market and Heavy Weather, Jean-Luc Ponty’s Aurora, Imaginary Voyage and Enigmatic Ocean, Stanley Clarke’s Journey to Love and School Days, Al Di Meola’s Land of the Midnight Sun and Elegant Gypsy, George Duke’s The Aura Will Prevail and Liberated Fantasies, the Billy Cobham-George Duke Band’s Live on Tour in Europe, John Abercrombie’s Timeless and Jeff Beck’s Blow By Blow.

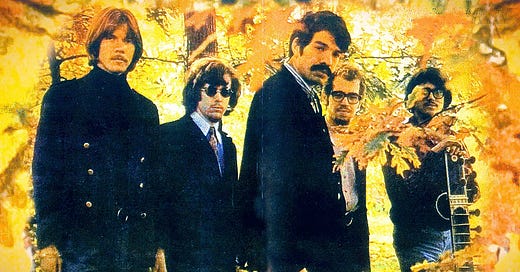

But in absorbing that much exhilarating fusion music through records and the countless concerts I attended while growing up in Milwaukee, I missed something. Call it the primary source or the missing link between rock and jazz, long before the term ‘fusion’ came into use. But I had somehow missed out on The Free Spirits. Established in Greenwich Village in the mid ‘60s, this renegade group of guitarist Larry Coryell, bassist-vocalist Chris Hill, guitarist Columbus “Chip” Baker, saxophonist Jim Pepper and drummer Bob Moses, bridged the worlds of rock and jazz before Hendrix, before Miles, before Tony Williams, even before Zappa did.

The Free Spirits’ debut on ABC Records, Out of Sight and Sound was recorded at the famous Rudy Van Gelder Studio on Sept. 14, Oct. 5 and 18, 1966, just a few months after Bob Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde, the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds and the Beatles’ Revolver came out. Released in January, 1967, it proceeded the release of Hendrix’s Are You Experienced by seven months, Tony Williams Lifetime’s Emergency! by two and a half years, Miles’ Bitches Brew by three years.

“I have to give Coryell credit,” said his Free Spirits bandmate Moses (listed as “Bobby” Moses on Out of Sight and Sound). “He was the first musician that I met in New York who was equally dextrous in both the jazz bag and the rock bag. He understood both worlds really well, and I think it took somebody like that to make the rest of us all appreciate rock & roll. I have to admit that I was a terrible bebop snob before I met Larry. I used to think that if you couldn’t swing and make the changes and play bebop, you were bullshitting. The very first time I heard Larry, he was playing bebop like Wes Montgomery, and I thought, ‘Wow, this guy’s a great player!’ Next time I heard him, he was playing a Chuck Berry thing, and really playing it well. I think that because of the fact that I saw his jazz chops first and had the respect, it made me take the rock thing seriously. So I started to listen to rock after that and found that there were things I liked.”

A Texas-born, West Coast-bred lad of 24 when he arrived in New York City from Seattle in 1965, toting a Gibson Super 400, Coryell dug Kenny Burrell and Barney Kessel while his favorite album at the time was The Incredible Jazz Guitar Of Wes Montgomery. He had great taste and unlimited potential, plus chops to burn. But something happened to alter his plans of becoming the next Wes Montgomery. By 1966, culture shock had set in, resulting in an abrupt change of course. “Everybody was dropping acid, and the prevailing attitude was ‘Let’s do something different,’” Coryell recalled. “We were saying, ‘We love Wes, but we also love Bob Dylan. We love Coltrane, but we also love the Beatles. We love Miles, but we also love the Rolling Stones.’ We wanted people to know that we were very much a part of the contemporary scene, but at the same time, we had worked our butts off to learn all this other music too. It was a very sincere thing. And what came out of it ultimately became a very big, lucrative movement.”

In a recent Zoom interview with Moses, now 77, from his second home in Molde, Norway (he splits his time between there and Memphis, where he moved five years ago), the drummer explained: “The Free Spirits was absolutely like nothing else. It was like Coltrane/Albert Ayler meets Motown, B.B. King and the Beatles. Because the songwriting was great in that band, but it was also so free having Jim Pepper blowing tenor the way he did. We were supposed to be playing rock ’n’ roll but we’d start our sets with Pepper doing a 20-minute unaccompanied tenor sax solo. Things like that were unheard of in 1965 for rock groups.”

“And Coryell was...WOW!,” Moses continued about the guitarist who also doubled on sitar, as he did here on “I’m Gonna Be Free,” a tune also marked by Pepper’s free-flowing flute work:

“Coryell was getting feedback with his guitar long before I heard Hendrix or Sonny Sharrock or Derek Bailey do it,” continued Moses. “Now there’s probably a bunch of avant-garde guitar players using feedback, but he was the first one that I heard doing that. So Coryell was really an eclectic guy, but he could also play as beautiful and straight ahead as Wes Montgomery. He did a record later on called Lady Coryell (Vanguard, 1969) where he does a beautiful jazz ballad version of ‘You Don't Know What Love Is.’ So he had that whole world covered as well."

Moses said of The Free Spirits’ debut studio date: “The record company tried to hold us down, which is why we all hated it at the time. But now I can listen to it and say, ‘Yeah, it’s still great.’ But then there was a live gig we played at the club called The Scene in New York (on Feb. 22, 1967) which eventually came out (in 2011) on a British label called Sunbeam Records. And you hear more of what we sounded like live on that one. We opened that night at The Scene playing our very tight rock set because Bill Graham was in the audience and we were hoping that he would take us on and make us stars, you know? Then he left for the second set and we took some pretty strong psychedelics. Yeah man, that was when we were young and wild. So things opened up considerably on that second set, and then we were joined on stage for a couple of songs by Dave Liebman, Randy Brecker and guitarist Joe Beck. We did a version of our tune, ‘I Wanna Be Free (For the Rest of My Days)’ that sounded like Trane’s Ascension meets rock ’n’ roll. ”

As Coryell once put it: “The Free Spirits came about as a result of five tripped-out cats from all parts of the world who moved into the same block of the same neighborhood. We felt that we would be years ahead of our time if we made the music we wanted to...what later became known as jazz-rock.”

The Free Spirits were the house band at The Scene (Steve Paul’s famed club located in the basement of 301 West 46th Street in the heart of New York City’s Theater District). As Moses recalled, “We played three weeks opposite the Velvet Underground. I guess now they’re considered an important band, but I thought it was the worst music I had ever heard. And quite a few characters would come through there. Remember the guy Tiny Tim, who used to sing in falsetto? He sang there every night. One time I went into the bathroom and Allen Ginsberg was teaching Tiny Tim how to sing ‘Hare Krishna.’ That was a surreal moment that happened at The Scene that I never forgot.”

“So we played The Scene every night there and sometimes famous rockers would come down after their gig at Madison Square Garden to hang and sometimes sit in. We got to play with some of the cats from the Young Rascals. Mitch Ryder from the Detroit Wheels sat in with us. Hendrix sat in with us one time and he was so intimidated by Coryell that he played bass, he didn’t want to play guitar. We had all kinds of people who would come down and sit in with The Free Spirits. Randy Brecker used to come down and sit in with us, and that was before he formed Dreams with his brother Michael and Billy Cobham. Other cats like Dave Liebman and Arnie Lawrence and Gary Burton used to sit in with us. In fact, that’s how Gary Burton discovered Lary Coryell, by coming down and sitting in with us. He’d bring his vibes down the stairs at The Scene to sit in with The Free Spirits.”

While The Free Spirits may have pioneered the blurring of borders between rock and jazz, flutist Jeremy Steig soon followed suit with his early fusion band The Satyrs, featuring guitarist Adrian Guillery, Warren Bernhardt on electric piano, Eddie Gomez on bass and Donald MacDonald on drums. Their self-titled 1968 album for Reprise Records included psychedelic numbers like “In The World of Glass Teardrops” and the bluesy “Superbaby.”

“The next jazz-rock group I ever heard of after us was Jeremy Steig & The Satyrs,” Moses confirmed. “And Jeremy was the world’s loudest flute player. I mean, he came to gigs with like stacks of Marshall amps. I never heard flute played like that before.” (Steig would later followup with his 1972 Groove Merchant album Fusion, featuring Jan Hammer on electric piano, Gene Perla on upright and electric basses and Don Alias on drums, and also 1975’s Temple of Birth with guitarist Johnny Winter, electric bassist Anthony Jackson, electric pianist Richie Beirach and powerhouse drummer Alphonse Mouzon).

By 1967, Coryell left The Free Spirits to join Gary Burton’s group. Moses also joined Burton because, as he said, “I knew that it wasn’t going to be the same without Coryell.” Pepper, Hills, and Baker subsequently formed the band Everything is Everything with Lee Reinoehl on Hammond organ and both John Waller and Jim Zitro on drums. In 1969, Vanguard released their self-titled album, which included Pepper’s composition “Witchi Tai To,” a tune that The Free Spirits had played under the name “Peyote Song” (as it’s listed on Live at The Scene, February 22, 1967). It was subsequently recorded by Pepper on his 1971 debut album, Powwow (on Herbie Mann’s Embryo Records label). A statement of 12 songs and chants of Native American music with appearances by Coryell, pianist Tom Grant on piano, bassists Chuck Rainey and Jerry Jemmott, drummers Billy Cobham and Spider Rice and Jim’s wife Ravie Pepper on flute, it included stories from his father Gilbert Pepper about the Seneca Nation.

Here’s the same tune from Pepper’s 1971 debut, Pepper’s Pow Wow, with Larry Coryell on guitar:

And here is Pepper’s version on 1987 album Comin’ and Goin’ with John Scofield on guitar:

And check out Coryell’s wicked wah-wah guitar solo on this number from Pepper’s Pow Wow:

Regarding The Free Spirits’ Out of Sight and Sound, Jay Lustig wrote for Inside Jersey: “I believe it’s a great album that encapsulates the liberating experimentalism of ’60s rock as effectively as many of its more famous contemporaries.” (The piece memorialized Lustig’s father Bruce, who managed The Free Spirits and got them their first record deal on ABC Records, recorded at Van Gelder Studio in Englewood, Cliffs).

nice article, Bill. where does Blues Project ( with “ Flute Thing”) fit in? Or “ Eight Miles High”, The Child is Father to the Man” by Al Kooper’s BS&T or Tim Buckley’s albums? where was Pat Martino when The Free Spirits and Jeremy and the Satyrs appeared?

Fine guitarist though he undoubtedly was,Coryell made many poor choices ( and I'm not talking about his singing) along his career and with record companies,attempting to be all things to all men. The result was a scatter gun discography of great albums mixed with garbage which contributed to his lack of relative recognition and commercial success. As to one of the originators of jazz rock,look across the pond and the Graham Bond Organization from the early 1960's. Nobody invented Jazz Rock.