Life-Changing Memories of Jimi Hendrix

The guitar god and revolutionary figure wouldve turned 82 today, Nov. 27

I’m thinking today, on what would’ve been the 82nd birthday of Jimi Hendrix (and also just happens to be the 79th birthday of Randy Brecker), about how Jimi came into my sphere of influence in 1967, like he was shot out of a canon. And then he was gone just three years later. The mind boggles in terms of what he might have done, musically and culturally, if he had not checked out on Sept. 18, 1970, just two and a half months shy of his 28th birthday (roughly my daughter’s age today).

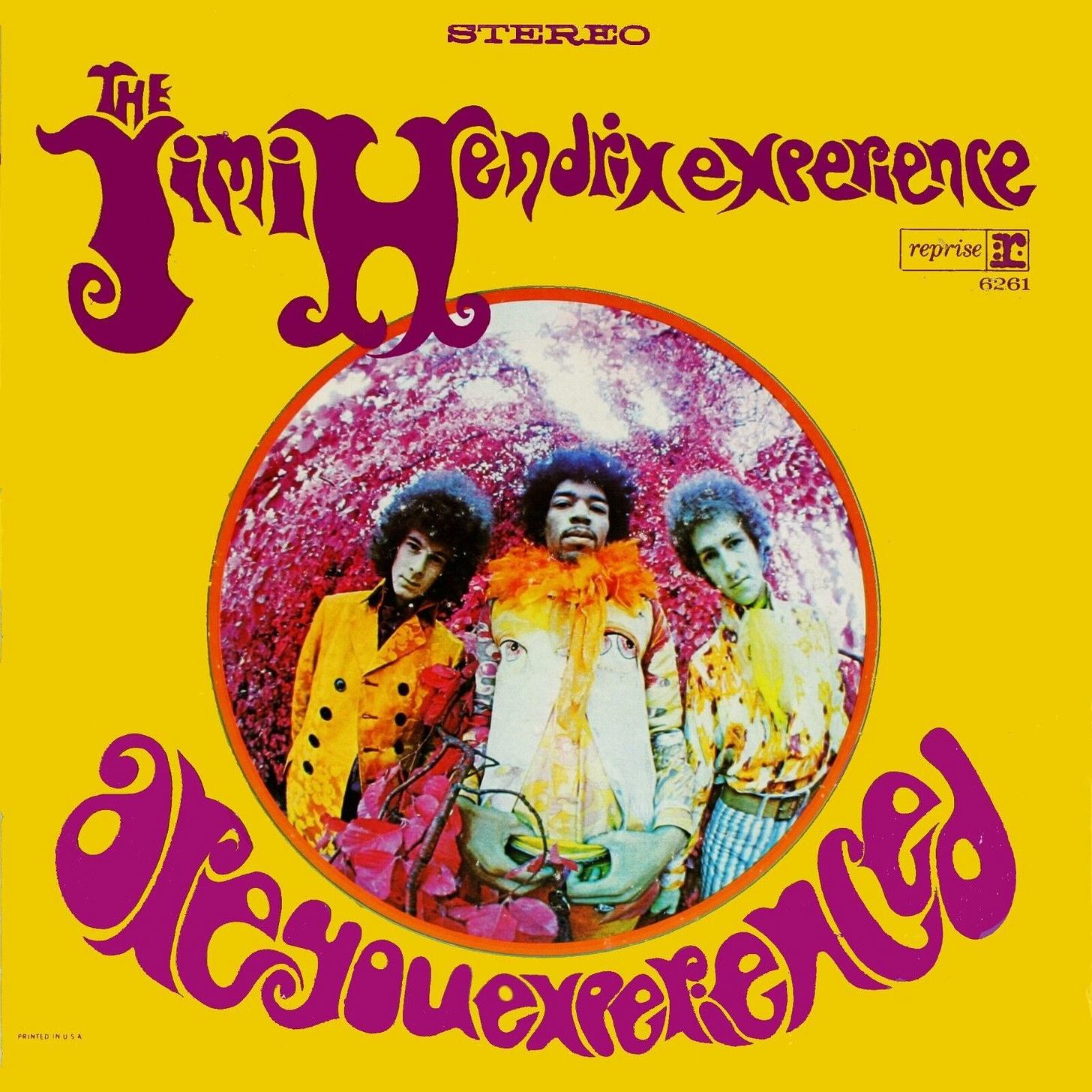

Are You Experienced, which was released on August 23, 1967 in the States (it had already come out in the U.K. on May 12) was the first album that I bought with my own money, and it blew my 13-year-old mind.

I can vividly recall staring endlessly at Karl Ferris’ fisheye lens cover photo of Hendrix sporting a psychedelic jacket with a pair of eyes on the front and wearing an orange scarf around his neck, posing next to his Experience bandmates Noel Redding and Mitch Mitchell, both equally decked out in audacious threads from King’s Road boutiques of the day. To my young Midwestern eyes, they seemed like time travels from the future. But the sounds inside were even more mind-expanding. Some 57 years later I can still fee the adrenaline rush I got from dropping the needle of my portable Zenith record player with detachable speakers on the opening track, “Purple Haze.” That was the shot heard ‘round the world, just as Jaco Pastorius’ “Donna Lee” would be nine years later.

The second track on Are You Experienced was “Manic Depression” (ironically, what Jaco would later suffer from in the mid 1980s, though by then it was called ‘bipolar disorder’). Though I wasn’t yet hip to what a 9/8 time signature was at the time and probably had never heard any drummer play over the bar line like Mitch does on that tune (I had not heard Elvin Jones by that point). Plus, the sheer heaviness of Jimi’s guitar, which I could feel in my chest, along with his sexy juke joint vocals and celestial guitar solo, absolutely seared my soul.

“Hey Joe” had already been out as a single, which I heard. A sweet enough ballad, to be sure, but it was Jimi’s lyrical solo on that number that really grabbed me. And he sang with a kind of raw, earthy abandon on that tune that was at once menacing and liberating, like Muddy Waters, Buddy Guy and Junior Wells before him. “Love or Confusion” struck me as a trifle, a throwaway tune in Jimi’s psychedelic bag, though his lyrical and radically-panned solo was lovely. And “The Wind Cries Mary,” a soft, Curtis Mayfield-inspired ballad with thoughtful lyrics, provided some mellow relief from all the tumult, which I actually preferred.

“Fire” is a bit of funk and soul coming out of James Brown and possibly influenced by the R&B groups that Hendrix gigged with before forming his Experience, including the Isley Brothers, Curtis Knight & The Squires and Little Richards’ backup band, The Upsetters, featuring vocalists Buddy and Stacy. Jimi’s other signature song on his first album was “Foxey Lady,” a heavy-duty slow-grooving tune with scorching guitar solo that may have served as a prototype for the heavy metal bands like Black Sabbath and others that followed in Jimi’s wake.

“I Don’t Live Today” only hinted at the visionary, acid-soaked six-string work to come on mind-stretching masterpieces like the free jazz-inspired “Third Stone From the Sun” (featuring Mitch Mitchell’s most Elvin-esque playing on record) and the revolutionary backwards guitar effects on the drone-oriented title track. With Mitchell’s military snare beat joining with Hendrix’s backwards muted/percussive guitar strumming, mesmerizing vocals and brain-melting guitar solo, “Are You Experienced?” was an anthem for the time, a kind of call to arms. And I was fully down to enlist in the Hendrix Army.

My Hendrix obsession only escalated with the release of Axis: Bold As Love the following year (January 15, 1968). I distinctly remember removing the detachable speakers from our portable record player and holding each one tightly against my ears while turning up the volume so that I could inject the low-end vibrations and wah-wah guitar licks from “Little Miss Lover” directly into my brain, like a drug.

The opening track from that album, “EXP,” was a barrage of white noise and experimental stereo panning pre-dating Frank Zappa’s “Weasels Ripped My Flesh” and Lou Reed’s Metal Machine Music by some years. Elsewhere on Jimi’s sophomore outing, I dug Mitch Mitchell’s Elvinesque playing on “If 6 Were 9,” loved the backwards guitar effects on “You Got Me Floating” and “Castles Made of Sand” and admired the hipness of Mitchell’s swinging brushwork on “Up From the Skies” and Jimi’s masterful chordal work and inherent melodicism on “Little Wing.”

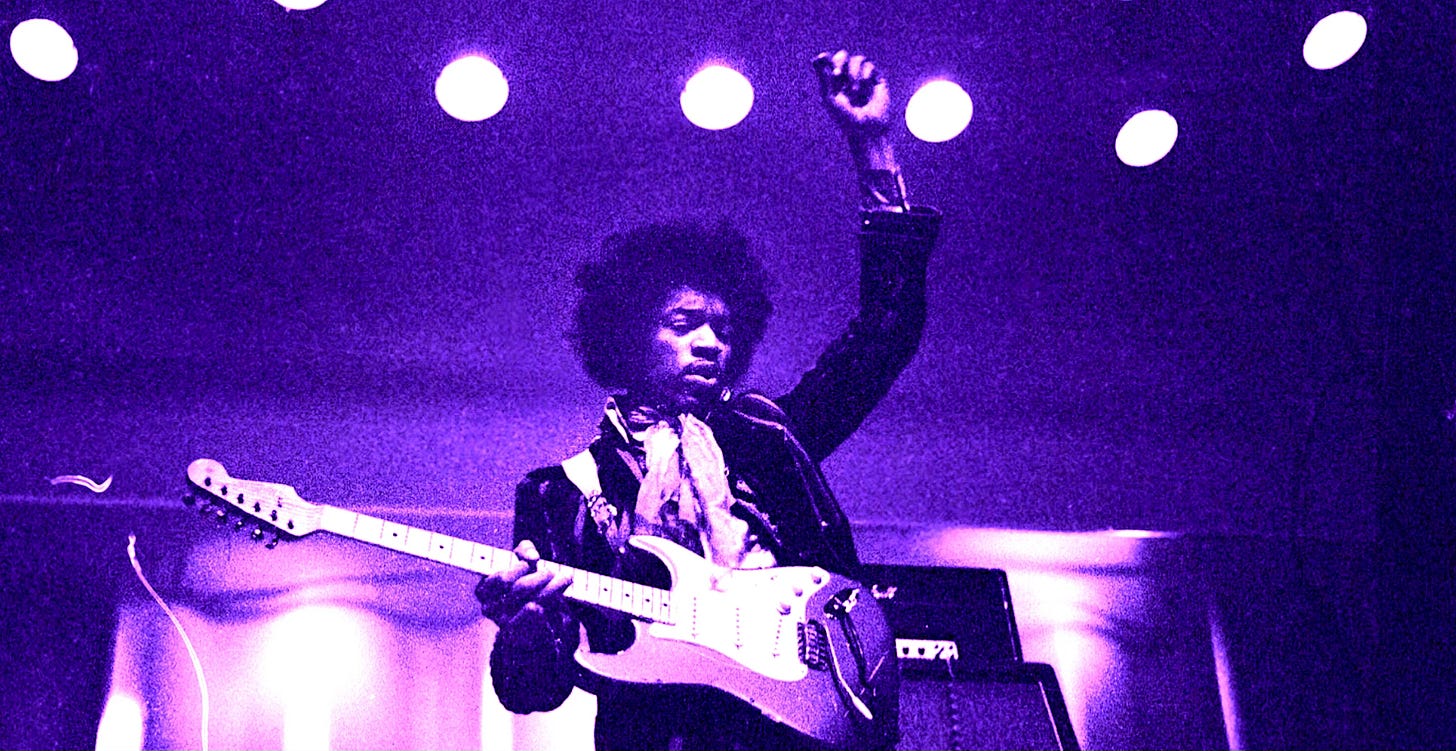

There followed the monumental double album Electric Ladyland (released Oct. 16, 1968) and Jimi’s Smash Hits (released in the U.S. on July 30, 1969). Then came the powerhouse live album, Band of Gypsys, recorded on New Year’s Eve into New Year’s Day at the Fillmore East in New York City and later released on March 25, 1970. Two months later, on May 1, 1970, I witnessed Hendrix perform (with bassist Billy Cox and drummer Mitch Mitchell) at the Milwaukee Auditorium. I went with my best pal Rick Weinman. Here’s a set list from that unforgettable show (courtesy of The Milwaukee Journal and OnMilwaukee.com):

Spanish Castle Magic

Lover Man

Hear My Train a Comin’

Ezy Ryder

Freedom

Message of Love

Foxy Lady

The Star-Spangled Banner

Purple Haze

Voodoo Child (Slight Return)

I had a math teacher then at Samuel Morse Junior High School named Mr. Fisher, who was an exceedingly hip black man from Seattle who played piano (in shades with Sammy Davis-styled medallion around his neck and Nehru jack) at the teachers talent show earlier that year in the school auditorium. Mr. Fisher also claimed that he knew Jimi Hendrix from his earlier days in Seattle, when he played in a band with the developing young guitarist. He assured me and Ric that he could get us backstage to meet Jimi and get his autograph. So after the show we hooked up with Mr. Fisher by the backstage door. He ended up going back to reminisce with Jimi without us, but he returned with autographs in hand, which he gave to each of us. I held onto that Hendrix signature for years. He had signed the opening page of a multi-page spread in the Oct. 3, 1969 issue of Life magazine (“An Infinity of Jimis: Jimi Hendrix photographed by Raymundo de Larrain”) that I had kept for years until finally giving it up to a professional autograph collector friend of mine who later left town.

Three and a half months after seeing the Jimi Hendrix Experience in concert at the 6,000-seat Milwaukee Auditorium (top tickets were $5.50), he died of asphyxia while intoxicated with barbiturates and sleeping pills in his sytem. Hendrix had been sharing a bottle of wine in the London flat of Monika Dannemann, a German figure skater and painter he had been in an off-and-on relationship with. They had stayed up all night talking, finally going to sleep at 7 a.m. Dannemann awoke around 11 a.m. and found Hendrix breathing but unconscious and unresponsive. She called for an ambulance at 11:18 a.m., and nine minutes later paramedics transported Jimi to St. Mary Abbots Hospital, where doctor John Bannister pronounced him dead at 12:45 p.m. on Sept. 18, 1970.

Twelve years later, for the October 1982 issue of Downbeat magazine, I wrote the following piece:

Jimi Hendrix: The Jazz Connection

by Bill Milkowski

DON'T BOTHER LOOKING UNDER ‘H’ FOR the name of Jimi Hendrix in any current jazz encyclopedia or text on the market. You won’t find it. Authors and archivists over the years have slighted Hendrix in the jazz history books, failing to recognize any contribution that Jimi may have made to the music (although Down Beat readers did vote him into the Hall of Fame in 1970). Yet Hendrix, who would have turned 40 this year, was clearly at the forefront of a movement that gradually brought about the ultimate cross-pollination of rock and jazz.

Miles Davis is generally credited with originating so-called fusion music in 1970 with his landmark Bitches Brew, which sold a half million copies in its first year. But groups such as Dreams (with Billy Cobham, Michael and Randy Brecker) or the British group Soft Machine had already been toying with the idea in 1969, and Hendrix had hinted at this fusion of idioms as early as 1967 with his revolutionary debut album, Are You Experienced.

Given Miles’ stature in the jazz world, he was probably the only one at the time who could have solidified the movement by lending itcredibility. For this reason, he may in fact be considered more of a popularizer of fusion music than its original innovator. By the time Bitches Brew hit, Hendrix had already been there, if only in an embryonic form.

Before Hendrix, the lines were more clearly drawn — there was rock on the one side and jazz on the other, with blues straddling the fence. After Hendrix, nothing would ever be quite so cut-and-dried. The impact of his explosive emergence in 1967 stretched the boundaries of rock, and at time of extreme exploration (“Third Stone From The Sun” from Are You Experienced or the free-form tag on “If 6 Was 9” from the follow-up album, Axis: Bold As Love) touched directly into the realm of jazz, whether or not he actually intended to.

There is a solid body of evidence supporting the theory that Jimi was indeed moving away from more simplistic forms of rock and beginning to embrace jazz more closely. Right up to the time of his death on September 18, 1970, he often mentioned a dream he had for a big band setting with vocal backing that would help him work out new musical ideas he had. In one of the last interviews of his life, appearing in Melody Maker magazine on Sept. 13, 1970, Jimi revealed some startling insights about the state of his music and where he would have liked to take it:

“I’ve turned full circle. I’m right back where I started. I’ve given this era of music everything, but I still sound the same. My music’s the same and I can’t think of anything new to add to it in its present state. When the last American tour finished, I started thinking about the future, thinking that this era of music sparked by the Beatles had come to an end. Something new has to come, and Jimi Hendrix will be there.”

He went on to speculate about his ideal orchestra to carry out these new musical ideas he was hearing: “I want a big band. I don’t mean three harps and 14 violins. Imean a big band full of competent musicians that I can conduct and write for. And with the music we will paint pictures of Earth and space so that the listener can be taken somewhere.”

Hendrix would come within a week of realizing his dream band. He died while on tour in England, shortly before he was to begin preliminaries on a collaboration with Gil Evans. The respected jazz arranger was fashioning an album of Jimi’s tunes and wanted Hendrix himself to be playing on top of his big band arrangements, just as he had done with Miles on Miles Ahead in 1957, Porgy And Bess in 1958, and Sketches Of Spain in 1959. Evans eventually completed the project in 1974 using Japanese fusion guitarist Ryo Kawasaki for the guitar parts on The Gil Evans Orchestra Plays The Music Of Jimi Hendrix. That posthumous release contained such lyrical Hendrix classics as “Castles Made Of Sand,” “Little Wing” and other selections that Evans presented in an all-Hendrix tribute concert at Carnegie Hall as part of the New York Jazz Repertory Company’s 1974 season.

Jimi’s body was buried at the Greenwood Cemetery in Seattle on Oct. 1, 1970. Included at the funeral among the mourners were Jimi’s father Al Hendrix, his brother Leon Hendrix, drummers Buddy Miles and Mitch Mitchell, bassist Noel Redding, bluesmen Johnny Winter and John Hammond Jr., and Miles Davis, whose presence there was as much a symbolic gesture as one of true friendship. It was in essence a statement of support for Jimi’s music. And with Miles’ stamp of approval, other jazz musicians could feel more comfortable about borrowing from this rock idiom as well.

Today, nearly every young fusion musician who came up with rock during the ‘60s and later got formal schooling in jazz conservatories will invariably list the name of Hendrix alongside the names of Coltrane, Bird and Miles as major influences.

Mike Stern, who plays guitar in Miles’ latest edition, and highly-touted fusion guitarist Al Di Meola have both captured some of Jimi’s fire in their own playing, but their appreciation of Hendrix goes well beyond the hot licks and biting sound he patented. “One of my favorite Hendrix songs,” says Di Meola, “was a very pretty, very underrated tune he did on his first album called ‘May This Be Love.’ He does this solo that sounds like his guitar is underwater, which was so totally foreign to me at the time. I mean, there I was, 13 years old in Bergenfield, New Jersey, learning everything from jazz to bossa nova to classical from my mentor [guitar teacher Robert Aslanian], and this guy comes out with underwater guitar sounds! It was so revolutionary at the time. Hendrix was such an innovator. He was just into experimenting with sounds and taking tunes out with long solos that took you on a little bit of an adventure. And this is what is gradually slipping away in the music industry today, not so much in jazz but especially in the music you hear on the radio. It’s so hip to be able to be as free and experimental as Hendrix was, but today the pressure is on so much for anyone who’s into the business of selling records to make pop music in the A-B-A form. And I don’t think that the pressure was on as heavily back then.”

Of the famed Hendrix technique, Di Meola adds, “His soloing was definitely in the jazz tradition, and a lot of members of the jazz community picked up on it. Not everyone, of course — there’s a lot of players from the old school who couldn’t stand to listen to Hendrix. But of my generation, most everyone will admit that Jimi was a leader.”

Mike Stern remembers Hendrix mostly for the evocative quality of his playing on tunes like “The Wind Cries Mary” from Are You Experienced and “One Rainy Wish” from Axis: Bold As Love. “His playing on those tunes is so lyrical. It has that same singing quality that Idig in Jim Hall's playing or in Wes Montgomery's playing, But the thing about Hendrix was he had that sound, he would articulate that lyrical feeling with a fatter sound on his Strat than you could get with a regular hollow-bodied jazz guitar.”

“Jimi was definitely a legato player, and whether he intended to or not, he started a movement among guitar players with his long sustaining, legato lines,” Stern continues. “He sounded more like a horn player than anyone before him, and he influenced everybody that followed him. I’m after that same horn-like quality in my own playing, either when I’m with Miles or when I’m playing a straight ahead bebop gig. Of course, on a bebop gig I’ll go for a darker, warmer sound, more like Jim or Wes, but Miles wants me to play loud. At Avery Fisher Hall last year [where Miles unveiled his current group at the 1981 Kool Jazz Festival], he went over and turned my amp up at one point. And he’s always saying things to me like ‘Play some Hendrix! Turn it up or turn it off!’ Miles loves Hendrix. Jimi and Charlie Christian are his favorite cats as far as guitarists are concerned. So right now with this band he wants to hear volume. My own natural instinct is to play a little softer, which I’ve been able to do on tunes like ‘My Man Is Gone,’ where my playing is a little darker. But Miles wants me to fill a certain role with this band, so I’m playing loud and my solos are usually speeded up to double-time, where I have to play kind of rock-style, whatever that is. So while I’m going for Jim and Wes, there’s some Jimi in there too, I guess.”

Fusion pioneer Larry Coryell speaks of Hendrix as having the talent of Stravinsky. Others have likened his inventive instincts to Omette Coleman’s visionary concepts. In fact, the ultra-funky, multi-layering guitar textures that Jimi explored in the studio on cuts like “Night Bird Flying” (which was to have appeared on a double LP Hendrix was working on at the time of his death called First Rays Of The New Rising Sun but was later included in the posthumously released LP, Cry Of Love) suggest some of the sounds that Coleman would expand on years later with his electrified Prime Time band. And today, many of the harmolodic offshoots picking up on Coleman’s lead —groups like Material and Curlew or solo artists like guitarist James Blood Ulmer — can trace their musical roots directly to Hendrix.

The link between Hendrix and Ulmer becomes especially eerie when you listen to Blood's vocal style on tunes like “Stand Up To Yourself” and “Pleasure Control” from his Free Lancing album. His slightly strangled, semi-talking yet highly expressive singing style on those cuts is hauntingly reminiscent of Jimi’s own husky-toned, sensual style.

Another fusion pioneer, guitarist John McLaughlin, calls Hendrix a revolutionary force. “Jimi single-handedly shifted the whole course of guitar playing, and he did it with such finesse and real passion.”

But perhaps Jaco Pastorius put it best, in his own succinct way, when asked to com- ment on what influence Hendrix has made on the current state of jazz. From his base in Ft. Lauderdale, Florida, where he is hard at work on his next solo album [which turned out to be Word of Mouth], the ex-Weather Report bassist summed it up with: “All I gotta say is, ‘Third Stone From The Sun.’ And for anyone who doesn’t know about that by now, they should’ve checked Jimi out a lot earlier.”

He’s referring to the extended ‘sound painting’ that Hendrix introduced on his debut album, Are You Experienced. In that number, drummer Mitch Mitchell displays his fondness for jazz (his background with the Georgie Fame band gave him a foundation in jazz rhythms), and Jimi blows what amounts to free form sax lines on top of it, perhaps borrowing from the free jazz movement which was in its ascendancy at the time with John Coltrane as its leading light. Jaco invariably pays homage to Hendrix during his live performances by using “Third Stone From The Sun” or “Purple Haze” as a springboard for one of his customary fuzzed-out feedback sessions on his beat-up Fender bass. And he generally sandwiches that segment between homages to Coltrane (“Giant Steps”) and Charlie Parker (“Donna Lee”), as if to demonstrate some kind of common thread among these three musical forces.

Of course, Jimi never presumed to be a jazz player. He was actually shy about approaching jazz musicians, probably because he could neither read nor write music. But by the summer of 1969, he was listening to more jazz, enjoying the sounds of Coltrane, Coleman, McCoy Tyner and Rahsaan Roland Kirk, the latter who was like an idol to him. Jimi’s own musical ideas were probably closer to Kirk’s than to the modal concepts of Coltrane or Miles. And since Hendrix was able to play three guitar parts simultaneously, he must have felt an immediate affinity for Kirk, who could play three wind instruments at once. Plus, Kirk’s amazing mastery of circular breathing techniques allowed him to blow unusually long, sustained lines, which matched Jimi’s own screaming legato guitar lines.

From the start of their early jams in London at Ronnie Scott’s club (around the early part of ‘67), Kirk and Jimi communicated on a mutual plane, recognizing that the blues was at the heart of their respective styles. They also shared a common feel for rhythm, which was all-important to Jimi’s playing. The rhythm of the guitar, he felt, was the key to blues, jazz and rock. He had forged his own solid rhythmic comping style while playing backup on the chitlin’ circuit during the early ‘60s with the likes of Sam Cooke, Ike & Tina Turner and Little Richard before moving to New York and taking up with the Isley Brothers and Curtis Knight. Young British counterparts like Eric Clapton or Jeff Beck didn’t have anything remotely as earthy and real to draw from in their formative years as guitarists, having learned nearly all their blues licks from records and radio rather than by osmosis and experience, as Jimi had. As a result, their respective styles come across as far more precise and intellectual than Jimi’s, lacking the grit and soul that was so much a part of the Hendrix style. Listen to Jimi’s extended bluesy jazz jam on “Rainy Day Dream Away” from Electric Lady. Together with organist Mike Finnigan, drummer Buddy Miles, bassist Noel Redding, and saxist Freddie Smith, Hendrix creates a swinging, intimate, smoky jazz club ambiance that is closer to Grant Green and Charles Earland than to the frenzy of a rock concert setting.

In the tradition of jazz players, Jimi loved to jam. He was wide open to a whole spectrum of musicians who were intrigued by new sounds and were not tied down to any one root. The list of names he jammed with during his brief but brilliant career is endless, including the likes of blues guitarist Johnny Winter, and jazz organist LarryYoung (KhalidYasin), who went on to participate in Miles’ now-historic Bitches Brew session, recorded in Columbia Studios in New York City on Aug. 19, 1969, the same day that the Woodstock Music Festival officially opened.

At one other fabled jam, Jimi locked horns with bassist Dave Holland, drummer Tony Williams and guitarist John McLaughlin. But McLaughlin is less than ecstatic about the result of this late-night session at Jimi’s Electric Ladyland Studios in Greenwich Village. “It was just a jam, really just a party in the studio. It was four o’clock in the morning, and everybody was a bit tired. I’ve only heard a few minutes of it on tape, but what I heard is just not up to it. If they found something that was really good, I’d be the first one to say, ‘Let’s release that.’ But there’s maybe three minutes of material, the rest is not up to par.”

Besides these celebrated jams, there are also rumors that some kind of collaboration took place between Jimi and Miles in the studio. It was around the time of Miles’ Filles De Kilimanjaro (recorded in 1968) that he began communicating with Hendrix. By this album, with its debut of electronic instruments and heavier beats, it was clear that Miles was beginning to flirt with rock, perhaps in response to the phenomenal success he saw that Hendrix had attained. By 1969, Miles was urged by Clive Davis, then president of Columbia, to face the rock challenge head-on. The result was In A Silent Way, on which Miles employed electric guitarist McLaughlin. Then in 1970 came Bitches Brew. As Miles has gone down in history as the Christopher Columbus of this new, uncharted land called fusion music, Hendrix might be considered its Leif Erikson. While the one consciously and meticulously established a strategy to explore this new land, the other merely sailed off course and aimlessly landed there, not really acknowledging the significance of his discovery at the time.

Producer Alan Douglas, who had worked with Eric Dolphy in his formative stages, was rumored to have tried orchestrating a summit meeting in the studio between Miles and Hendrix, but both were said to have a reluctance to work together. Douglas, who later gained control of some 600 hours of Hendrix tapes as the designated curator of the Hendrix estate, is of the opinion that Jimi was definitely heading to a closer connection with jazz at the time of his death. To further support his theory of Hendrix as an emerging jazz musician, Douglas released an album in 1980 called Nine To The Universe, a collection of jams with organist Larry Young and others that shows Jimi’s natural affinity for the jazz idiom.

In the early stages of hiscareer, it was easy for skeptics to dismiss Hendrix as nothing more than just another freaked-out rock star whose only contribution was his pioneering efforts in the mastery of decibels. His explosion onto the British scene in 1967, a carefully calculated campaign masterminded by impresario Chas Chandler, was met with almost unanimous ridicule by the London press, which immediately labeled Jimi as a kind of black anti-hero. One paper called him a Mau Mau in banner headlines while another tagged him as “The Wild Man of Pop.” Hendrix received similar treatment from the American press as well, at least initially. The New York Times, for example, referred to him as “a Black Elvis” in a laudatory review on Feb. 25, 1968. This early scrutiny obviously focused on Hendrix’s surface appeal and ignored the richness or depth of his musical ideas.

Of course, Jimi often gave the skeptics plenty of ammunition to write him off as an exhibitionist (he was thrown off a Monkees tour in 1968 for shocking the pre-pubescent teenybopper crowd with his so-called X-rated stage antics) or as a gimmicky carnival attraction (by virtue of his showy, acrobatic presence and dental daring on guitar) or as a jive-talking sexual tease (no doubt reinforced by such come-on tunes as “Foxey Lady” and “Little Miss Lover”). This was certainly a part of the Hendrix mystique in those early days of the Experience. But toward the end of his life, Jimi began expressing strong desires of shunning the whole packaged and processed world of pop and getting into more serious music.

As he put it in that final interview with Melody Maker: “The main thing that used to bug me was that the people wanted too many visual things from me. I never wanted it to be so much of a visual thing. When Ididn’t do it, people thought I was being moody, but I can only freak when I really feel like doing so. Now I just want the music to get across, so that people can just sit back and close their eyes and know exactly what is going on without caring a damn about what we are doing while we’re onstage.”

By 1970, with a collaboration with Gil Evans on the horizon, Jimi Hendrix had long grown beyond the showmanship of 1967, when he felt a certain amount of responsibility to play guitar with his teeth and smash amplifiers. He was indeed headed in more challenging musical directions, and we can only dream about how far he would’ve gone and where he would be today.

Nearly 20 years later, for the July 2001 issue of Jazz Times, I wrote this piece:

Jimi Hendrix: Modern Jazz Axis

By Bill Milkowski

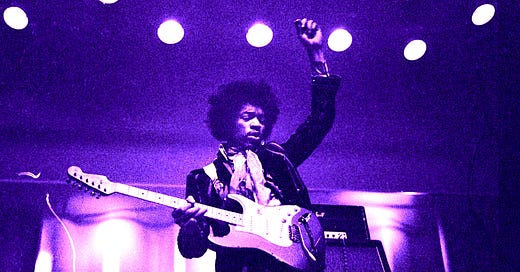

In 1965, my 11-year-old soul went into a nosedive when the Milwaukee Braves baseball franchise relocated to Atlanta. Gone were the heroes of my youth — Hank Aaron, Eddie Mathews, Warren Spahn, Rico Carty — sending me into a deep depression. I would be rescued two years later by Jimi Hendrix, who elevated me to delirious heights with a kind of god-sent otherworldly music that got into my bones and altered my life. With his frizzy Afro hair, Fu Manchu mustache and psychedelic ‘eye shirt’ beaming back at me through the purple-tinted fisheye lens cover photo of 1967’s Are You Experienced, Hendrix presented a provocative visage that made me forget all about Hammerin’ Hank and the rest. And the music contained on that perfect piece of vinyl was something else — loud, rebellious, exhilarating, nasty, dangerous, adventurous, totally transcendent. And jazzy.

As Jaco Pastorius put it, in assessing Hendrix’s jazz connection back in 1982: “All I gotta say is…‘Third Stone From the Sun.’ And for anyone who doesn’t know about that by now, they shoulda checked Jimi out a lot earlier. You dig?”

Miles Davis readily gave it up to Hendrix, as did Gil Evans, who marveled at his ‘onomatopoeic approach’ to guitar playing and later captured some of that quality on his 1974 recording for RCA, The Gil Evans Orchestra Plays the Music of Jimi Hendrix (with Ryo Kawasaki and John Abercrombie filling in the guitar chair that had originally been planned for Jimi). Tony Williams left Miles Davis in 1968 to form a band, Lifetime, which was partly inspired by the Jimi Hendrix Experience. And another Miles sideman, John McLaughlin, called Hendrix “a revolutionary force who single-handedly shifted the whole course of guitar playing.”

And while Jimi admired and respected Miles, he idolized Rahsaan Roland Kirk. Hendrix’s record collection, circa 1968, included Kirk’s Rip, Rig & Panic right alongside Jeff Beck’s Truth and the odd assortment of Bob Dylan, Tim Hardin, Albert King, Buddy Guy, Muddy Waters, Kenny Burrell, Wes Montgomery and Ravi Shankar LPs. In a March 1970 issue of Rolling Stone, writer John Burks reported on the apparent affinity that Jimi felt for Rahsaan: “It’s revealing to hear Hendrix talk about jamming in London with Roland Kirk, jazz’s amazing blind multi-horn player. Jimi was in awe of Roland, afraid that he would play something that would get in Roland’s way. You can tell, by the way he speaks of Kirk, that Hendrix regards him as some kind of Master Musician. As it worked out, Jimi played what he normally plays, Roland played what he normally plays, and they fit like hand-in-glove.”

By all accounts (including a snippet from John Kruth’s book Bright Moments: The Life & Legacy of Rahsaan Roland Kirk, which details their fabled jam at Ronnie Scott’s jazz club in London in the early part of 1967), Kirk and Jimi communicated on a mutual plane. Since Hendrix routinely layered three or more guitar parts on his recordings, he must have also felt an immediate affinity for the jazz iconoclast who could play three wind instruments at once. And Kirk’s amazing mastery of circular breathing allowed him to echo Jimi’s own sustained guitar lines. But their strongest bond came from recognizing that the blues was at the heart of their respective styles.

Kirk’s name came up once again when Hendrix mused to Britain’s Melody Maker in an impromptu eulogy: “I tell you, when I die I’m not going to have a funeral. I’m going to have a jam session…Roland Kirk will be there and I’ll try to get Miles Davis along if he feels like making it. For that it’s almost worth dying, just for the funeral.”

Of course, the Jimi Hendrix Experience had made several allusions to jazz along the way. Check out Mitch Mitchell’s slick timekeeping on “Manic Depression” and his incessantly swinging ride cymbal work on the middle section of the suite-like “Third Stone From the Sun,” both from Are You Experienced. Dig Mitch’s deftly swinging brushwork on “Up From the Skies,” his hip Philly Joe Jones-inspired fills on “Wait Until Tomorrow” and “Ain’t No Telling” or his freewheeling Elvin-esque abandon on “If 6 Was 9,” all from Axis: Bold as Love.

More proof of Hendrix’s jazz leanings can be heard on his 1968 two-record opus, Electric Ladyland. The extended bluesy jam on “Rainy Day Dream Away” with organist Mike Finnigan, drummer Buddy Miles, bassist Noel Redding and saxophonist Freddie Smith creates a swinging, intimate, smoky jazz-club ambiance that is closer in spirit to vintage Blue Note B-3 sessions than to any frenetic rock concert.

Producer Alan Douglas, who had worked with Eric Dolphy in his formative stages, was rumored to have tried orchestrating a session between Miles Davis and Jimi Hendrix, but both parties were said to be somewhat reluctant to make the first move toward that summit meeting. Douglas, who believes that Hendrix was definitely heading to a closer connection with jazz at the time of his death, released a posthumous album in 1980 called Nine to the Universe, a collection of casual jams at the Record Plant in New York from 1969 with Jimi interacting playfully with Tony Williams Lifetime organist Larry Young and Band of Gypsys drummer Buddy Miles. The Hendrix estate later sued to halt the subsequent rerelease of that album, which it considered a horrible and unrepresentative recording that mars the Hendrix legacy.

In 1988, Sting collaborated with the Gil Evans Monday Night Orchestra, performing live versions of “Up From the Skies” and “Little Wing,” the latter of which appeared on the pop star’s Nothing Like the Sun.

In 1995, Hendrix’s longtime engineer Eddie Kramer masterminded In From the Storm, an orchestral celebration of Hendrix’s music featuring jazz greats Tony Williams and John McLaughlin alongside Band of Gypsys bassist Billy Cox, rock-guitar heroes Carlos Santana and Steve Vai, bluesman Taj Mahal and Sting. More recently, MCA released South Saturn Delta, which includes some previously unissued studio tracks featuring Hendrix with a horn section for the first time in his career. As engineer Kramer says of that posthumous release, “It was a portend of things to come.”

Hendrix released only five albums during his lifetime. There have been about 500 bootlegs floating around since his death at age 27 on September 18, 1970. More than 30 years later, his name still registers shivers of excitement. He has been rediscovered by a new MTV-VH1 generation and appropriately enshrined in the Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland. There are various tribute recordings currently in the works and his estate (operating under the auspices of Experience Hendrix) has sanctioned annual Experience Hendrix tours.

Jimi played guitar with the rawness and directness of a Delta bluesman tapped into a million kilowatt power supply and filtered through the rainbow vision of Timothy Leary. His lysergic verse was as inspired and otherworldly as Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s and his sense of rhythm guitar playing was as solid and slinky as Jimmy Nolen’s. All this, plus the fact that he possessed the charismatic showmanship of a psychedelic Louis Jordan in the Age of Aquarius. He was a complete anomaly, the total package — what the Germans call gesamtkunstwerk. His influence on guitarists remains staggering; his influence on rock incalculable. But what was Jimi’s connection to jazz?

Bob Belden

Producer-composer-bandleader and noted Miles Davis scholar who has presided over the Miles reissues for Columbia/Legacy

Are You Experienced had a profound effect on me. Also, Jimi’s music — particularly the bass lines — directly influenced Miles Davis. If you listen to “Inamorata” from Live/Evil, that’s the bass line to Jimi’s “Fire.” And “Mademoiselle Mabry” from Filles de Kilimanjaro is derived from Jimi’s “The Wind Cries Mary.” “What I Say” from Live/Evil is basically “Message to Love” from Band of Gypsys, and so on. Miles had Michael Henderson play those kind of bass lines, and he had Jack DeJohnette play like Buddy Miles because that’s what he wanted to hear. He had Jimi Hendrix and Sly Stone in mind.

Hendrix wasn’t a jazz player, per se. He was essentially a blues guitarist who played with a lot of freedom within his own vocabulary. I don’t think he could’ve handled changes that well, but he didn’t need to. There was no parallel for him so it’s hard to imagine where he would’ve ended up had he lived. Would he have become a smooth-jazz guitarist? Maybe he’d end up playing “The Star Spangled Banner” with an orchestra at the halftime of the Super Bowl or in a Las Vegas show. As the song goes, “Who Knows?”

John Scofield

Guitarist-composer, former Miles Davis sideman and bandleader since the early ‘80s

When I first started to play guitar — this was before Hendrix — there was a chord known as the “Hold It” chord, an E sharp 9. It was based on a break tune that came from an older generation, a Bill Doggett song from the ‘50s. And when Hendrix started to play this chord in 1968, it became known as the Jimi Hendrix Chord. You can hear it on “Purple Haze.” So that’s a big influence right there.

I remember first hearing Hendrix’s music on the radio. It was on Murray the K’s show in New York. I didn’t know anything about him but the first album had just come out and I heard this on the radio and was instantly knocked out. It was coming out of a little transistor radio but it completely blew me away, so I went out and bought Are You Experienced the next day. I wasn’t a jazz guy yet; I was into Clapton and Jeff Beck. But Hendrix seemed to be on another level. I never heard anything that strong and I was just fascinated by it — the guitar playing and the beat and the whole thing. It seemed to me to be an extension of soul music and psychedelia combined with great blues guitar playing that related to B.B. and Albert King. I became a devotee and bought the next two albums, Axis: Bold as Love and Electric Ladyland. And I remember listening to those first three records all the time, trying to learn the licks and being totally into it.

And then I went to see Hendrix with the Experience at Hunter College in early ’69. I took the train in from Connecticut and it was a really, really incredible show. The way he played was so phenomenal and so loose and so soulful that I actually gave up rock ‘n’ roll guitar and decided to become a jazz musician because of him. I remember thinking, “I can’t do that. I’m just a little white boy from the suburbs of Connecticut. Forget it. It’s all over. This guy is so outgoing and incredible that I might as well give up on trying to be like that because my personality’s not that way.” But then I thought, “Maybe these jazz guys like Jim Hall and Wes Montgomery, if I practice hard enough, maybe I can get there.” Later on I was able to absorb some of that Hendrix influence and let it come through in my own playing, but at the time I was far too intimidated to do that.

I never thought of Hendrix as a jazz guitarist but I did think of him as an incredible blues player and an improviser in that tradition as well as someone who was improvising on a sonic level, experimenting with feedback and coming up with some incredible new sounds on his instrument. I didn’t see him as a guy playing rhythm changes, I saw him as a new branch of rhythm ‘n’ blues — R&B and psychedelia combined. It was this magical trip that he was going on with letting the music expand. And we all followed, to some degree.

Branford Marsalis

Saxophonist-composer and bandleader from New Orleans’ first family of jazz

As a kid I remember hearing “Purple Haze” on the radio but I didn’t really think of it as anything really earth-shattering. But the Band of Gypsys! Now that was earth-shattering! At the time I couldn’t think of why it spoke to me but it did, immediately. First of all, it’s a live performance so it’s not a bunch of overdubs after overdub after overdub. And it was at that line where rock ‘n’ roll could still be free, and that’s the thing that I dug the most. The shit was just funky the way Led Zeppelin was funky and the way The Beatles had a little groove to their shit, too. But those two groups never could get their bottom to have that funky-ass stank groove the way the Band of Gypsys did. Listening to Mitch Mitchell [with the Experience, it was clear that he was coming from a jazz background, particularly an Elvin Jones thing with all those triplets over everything. But listening to Buddy Miles just keep that pocket was really staggering shit for me. That doesn’t mean I didn’t dig the other shit like “If 6 Was 9” and “Manic Depression.” I dug it, believe me. But Band of Gypsys affected me in a much more powerful way. I would suspect that just by the energy on the stage that he really had fun with Billy Cox and Buddy Miles. Because, you know, if he had been playing with Buddy Miles from the beginning, songs like “Manic Depression” would not have worked. I don’t think Buddy Miles would know what a 9/8 feel was if it fell on him. But I think at the end of the day, Jimi was a groover, which is why songs like “Who Knows” and “Machine Gun” are so killing. I mean, you gotta be deep in the pocket for that shit to work. Those were his roots, and he smokes on that record.

Hendrix might have had an influence on individual musicians in jazz but he wasn’t a jazz musician himself. I mean, he had an influence on my jazz because everything that I listened to as a kid, I think, creeps in to the shit that I do now. When I hear Hendrix today it just reminds me of the blues on acid —hyper, hyper blues. He had all the elements of jazz because you know all the elements of blues are in jazz when it’s played right — spontaneity, creativity, improvisation, the blues itself, groove. He was definitely an improviser but he couldn’t play “How High the Moon.” And he didn’t need to. He always heard some other shit.

I don’t know if Jimi would ever have become a jazz musician. In a lot of respects, jazz probably would’ve been too limiting for him. You know, too many rules and shit. He just wanted to go up there and do whatever the fuck he wanted to do — all the time. Jazz is such a different aesthetic. He would’ve had to go into a serious amount of woodshedding, away from the scene. There’s just so much other shit he would’ve had to come back to, almost like starting from scratch. And I don’t know if he would’ve been able or wanted to do that. Or that he should have. The thing I love about him was he wasn’t a jazz musician but he was a grade A-1 bona fide fucking musician. That couldn’t be disputed. I can understand why Miles, being the forward-thinking cat that he was, particularly in the pop sense of the word — that was very smart of Miles to align himself with a cat like Hendrix. Jimi had his hit with “Purple Haze” but for the most part he was a counterculture cat, the fringe dude that all of the other cats went to check out, including Miles.

Randy Brecker

Trumpeter-composer-bandleader and former sideman for Horace Silver, Billy Cobham, Jaco Pastorius and Frank Zappa, he co-founded Dreams in 1969 and the Brecker Bros. band in ‘74

Do I consider Hendrix a jazz guitarist? Ah…no. But he was the epitome and essence of rock ‘n’ roll! Although he listened to jazz and was a great improviser, the parameters, vocabulary and sensibility were different and sometimes extremely divergent. Jazz is about finesse; Hendrix was as raw as it can get. Pitch, time and dynamics were not important in the Hendrix Experience. And quite frankly, remembering back, sometimes I had difficulty reconciling these items when I heard him, especially live. But the strong points of that group — raw energy, originality, balls, amazing tunes, conception and volume — were so overwhelming that the other points were literally blown away. I still get chills when I put on those records.

Probably the first time I heard Jimi was when he was jamming at The Scene in ’67. I also heard him at Electric Lady before it was turned into a recording studio [for a brief time it was a big club]. My first reaction was to run and stuff pieces of a napkin in my ears. I mean, that shit was loud! But it was also completely unforgettable from the second he walked on stage. You have to remember we had never seen anyone even dress like he did. This was back when you had to wear a suit to play bebop but really didn’t want to.

Jimi’s tunes and the words and his singing all were big influences on my own music. I loved his stream of consciousness lyrics and his singing because it was untrained and functioned as an organic part of the music. After I heard “Up From the Skies,” for instance, which was one of his most jazz-influenced songs, I wrote “Imagine My Surprise,” which became the title song of the second Dreams record. That was one of the few times in fact that I wrote something with only one influence and song in mind. His playing was an influence, too, for that matter. When I plugged into my effects [wah-wah pedals and delays] I always had him in mind, along with my jazz influences.

Had he lived, I think Jimi would have played and recorded under different settings, including some very jazz-influenced situations, such as his collaboration with Gil Evans, which was on the drawing boards right at the time he died. I also think his playing would have continued to develop but within a rock format and not really radically change that much. The last thing I would hope for him to become would be anything but what he was — the greatest and most original rock guitarist ever.

John Medeski

Keyboardist with Medeski, Martin & Wood, the godfathers of the jam-band scene

First time I heard Jimi I wasn’t really ready for it yet. I was really deep into jazz and classical music and I didn’t really get it at first. It might’ve been a record of greatest hits or something like that and I thought it was alright, but I think Axis: Bold as Love was the first Hendrix record that I really understood from a different perspective. For me, he’s probably the greatest musician of the last century in terms of really culminating everything.

What inspired me about Hendrix’s music was it was so rooted in the blues and then it also had this futuristic, god-like quality to it, like Bach has. And it was also very raw. Whereas, Bach is mathematically genius, Hendrix is soulfully genius. If I had to pick a small amount of music to put in a time capsule that would represent the human race, it would probably be Bach and Hendrix, just to show all sides of what we deal with as people expressing themselves through music. And the tune that was the one that slew me overall was his solo on “Red House” from Hendrix in the West. I love that particular one. I listened to it maybe 100 times in a row, over and over in my car, until I memorized it and could sing it note for note.

And to be totally honest, also tripping on acid to Hendrix was a revolutionary experience. I mean, it brings another dimension of music that is just phenomenal. Anybody who has done that knows. Otherwise, it’s impossible to explain it to somebody who doesn’t know what that’s about. It turns it into a spiritual experience. When you’re in it, it grabs you in a visual sense.

Hendrix had the same searching quality in his music that Coltrane had. In fact, his would be the third name I’d add to the time capsule — Hendrix, Bach and Trane. But Hendrix represented so many aspects of music. He was pop, he was blues, he was R&B, he was psychedelia. And jazz people eventually got around to seeing how great he was. But I never regarded him as a jazz musician. To me, he’s beyond that. He’s everything. Hendrix was the only guy I heard that made me wish I was a guitar player.

Vernon Reid

Guitarist, and one of the foremost exponents of the Hendrix legacy, was a member of Defunkt in the late ’70s, Ronald Shannon Jackson’s Decoding Society and Living Colour in the ’80s.

For me, it was Band of Gypsys. I was in high school in the early ’70s. There was a kid in a couple of classes above me, a senior, who said, “You play guitar? You oughta listen to Hendrix.” I remember seeing Hendrix on The Dick Cavett Show because back then if anyone black showed up on TV it was news, like “gather the family around.” I remember he was wearing all blue and I thought, “Wow, that’s so different.” But I was just a kid and my focus was elsewhere. I was more struck by the sight of him; I wasn’t really listening so intently to the music. But later on I started listening to Hendrix and it blew my mind.

This was at the time when the Vietnam War had been going on so long that I was actually wondering was it going to last long enough for them to draft me. It just seemed like there was no way out of it — just this endless quagmire. So hearing Jimi’s “Machine Gun” [from Band of Gypsys] really made quite a statement at that time. It was like a movie about war without the visuals. It had everything — the lyrics, the humanism of it, the drama of it, the violence of it, the eeriness of it, the unpredictability of it. I can’t imagine what it was like to have been in the Fillmore East and have that happen in the second set. If you were there it had to have changed your life, if not forever at least for a little while.

As far as electric lead-guitar soloing, Hendrix was one of the only cats to do that activity and have it extend beyond the notion of chops and scales or anything to where it literally melded itself into the fabric of society and the big questions of the day. And to my mind he did it twice. He did it with “Machine Gun” and he did it with “The Star Spangled Banner.” And in both instances, his playing, his improvising was woven into the fabric of the times. It was like Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech. Those were the kind of times that they were, and it seemed like only those times could have produced him.

On a playing level, Jimi was coming from a blues aesthetic, but he was a modernist. He took on Hubert Sumlin and Albert King but he was also of his time, the ’60s and all that meant. He was certainly a great improviser but when you listen to Hendrix’s solo there’s a certain palette harmonically that he works with. It’s basically the blues — a lot of dominant chords, major and minor, the occasional altered dominant chord like a 7th, D sharp 9, 11th chords. But it’s not like he’s dealing with the same palette as Wes Montgomery. He’s not dealing with bebop. At the same time, he’s not limited by anything. He just plays. You put him in any situation, I think, and he would play something profound. Because he’s not thinking about, “This is wrong.” He’s not coming from, “I’m wrong here and I need to fix it.” He just plays.

Hendrix arrived at some special place in the mid-’60s. He obviously worked very hard and he took a genius leap. Because there are recordings of Hendrix with Curtis Knight and King Curtis and he sounds like a decent rhythm guitar player. But he took the same fundamental leap that Charlie Parker took in his own right, that Ornette Coleman took. He took the great leap forward. And I think it’s fascinating when individuals do that because it seems like an individual is doing it but it’s like a whole network of things coming together to make that happen. There’s a whole community of voices in an individual coming together that are informing what ultimately results in him taking a leap. Leaving Seattle was taking a leap. I mean, we are a nation filled with Charlie Parkers and Jimi Hendrixes. The question is, “Who is gonna take that leap into the great nowhere?” And the thing about the great nowhere is this: no one approves of it. There was no agreement on Hendrix’s greatness when he first came out. Even when you read reviews it’s like “The guy’s playing too loud. Who does he think he is? He’s a clown, he’s jumping around.” He obviously took some moves from T-Bone Walker’s playbook but he had a vision thing, too. He went forward, forward, forward. He’s daunting in that he really always poses a challenge, like Picasso: “OK, this is what I did. It’s there in your life. Now you got to find it.”

Hendrix was a series of collisions and accidents and chances taken and leaps of faith. Plus, he had a certain kind of unassailable integrity that was always under assault, even by his fans, because everyone wanted him to be the Hendrix that they wanted him to be. So he was in constant turmoil with the management scene, with relationships, all of that. So if Hendrix hadn’t choked on his own vomit — well, he woulda had a life.

I would love to commission artists to come up with alternate histories of Hendrix. Hendrix is turned over that fateful night and he doesn’t die. What happens then? Does Hendrix join Emerson, Lake & Palmer? Does he hook up with Miles Davis? Does he join King Crimson? Does he break his band up, go to Jamaica and become a Rastafarian? Does he move to India or Morocco? Does he go into retirement? Does something even worse happen to him — “Foxey Lady” wine coolers or whatever? Does he get married and have a daughter who is a brilliant saxophonist who becomes the next Coltrane? Does he do the soundtrack to Five Easy Pieces. And what would happen to the music as we know it? Does Hendrix go completely underground or does he get together with Soft Machine or with Patrick Gleeson or Kraftwerk? It’s up for grabs. I would like to think the Hendrix in the early ’70s would’ve done something incredibly progressive for that time period. Like, in another world, maybe it would’ve been Jimi instead of Tommy Bolin playing on Billy Cobham’s Spectrum. Who knows? If Hendrix had lived, would he have hooked up with Marvin Gaye? Good god almighty!

David “Fuze” Fiuczynski

Innovative guitarist who has performed and recorded with a variety of jazz and pop artists, while also leading his own band Screaming Headless Torsos

My experience with Hendrix is a little bit different than most players. When I started guitar at age 13 [in 1977], I was a jazz head and I didn’t want anything to do with rock music at all. Then two or three years later, when I happily matured a little bit and realized that there’s more than just jazz out there, I really made a point to avoid Hendrix because I saw how easily people got sucked into his thing and they lost their own identity. So my first experience with Hendrix was actually one of trying to run away from him. I just remember thinking that Hendrix was dangerous.

Then in college, around ’83, I started checking him out. I think it was “Manic Depression” that first grabbed me. That’s really one of the first real heavy metal bebop tunes. I mean, if you listen to the drums, Mitch Mitchell is playing straight ahead on that. Maybe that’s one of the reasons I got drawn to it, because it had that jazz thing going on in there. Actually, by then I was into hard rock and punk and also fusion, but I also started to listen to Hendrix a bit. I actually had to learn a lot of his tunes for gigs — the Black Rock Coalition did Hendrix tributes and actually Me’Shell NdegéOcello was thinking about doing a Hendrix tribute album. And people would give me tapes to listen to which were basically best-of compilations, so I never really associated the individual tunes with albums. I just took them all in at the same time and started to learn them. And as I studied these tunes, I realized that I already had gotten a lot of him indirectly through other guitar players. You know, the wah-wah skronks, the whammy bar stuff that I got from other people. It was a revelation, like, “Oh! So this is where they got this from.” You know, Steve Vai’s wah-wah thing and his octave thing and Hiram Bullock had a certain thing that I thought was really individual, which I later found out he got from Hendrix. And that’s happened with probably 10, 15 guitar players that I’ve really checked out personally. They all borrowed from Jimi. So while I tried to avoid him I realized later when I came back that I wasn’t avoiding him at all because it was just impossible. His influence was just too pervasive.

I’ve covered a few of Jimi’s tunes over the years, including an unreleased Torsos version of “Little Wing,” which I’m proud to say doesn’t fall into wedding band/Misty” mode. I also covered “Third Stone From the Sun” on Jazz Punk. That was my own personal homage to him. It’s an attempt at trying to look at maybe the way that Hendrix might’ve done something if he were still alive. It’s got a Middle Eastern vibe to it, which is something I picked up from being in Morocco in 1992 for a gig I played with this Moroccan contingent. We rehearsed for 10 days in Marrakech in preparation for the World’s Fair in Seville, Spain, and all the Moroccan cats came up to me and said, “Yeah, Hendrix was here, Hendrix was here!” Apparently, he spent a lot of his leisure time there during the ’60s. And that sowed the seed of like, “Hmmm, what would’ve Hendrix done with this Middle Eastern stuff?” So this version is a little bit of an attempt of trying to figure that out.

Calling him a jazz musician is, to me, a little bit restrictive because the cat is also an unbelievable poet. That’s another thing of how he just sets himself apart from other guitar players. And even if he never soloed, some of his heaviest guitar shit is his comping. There’s a lot of cats who get beyond the notes, who transcend their instruments when they’re playing but the way he did it was really earthy. You got some people-they’re really heady, it’s a cerebral thing. But Jimi had that mind-body-spirit type thing going on-the lush written images that were mirrored with the lush soundscapes. He had like that double whammy. This cat just had so many different ways of grabbing you-wild solos, incredible orchestration, unbelievable lyrics-and then you get them all together with phat grooves and showmanship. It’s like a Stravinsky ballet. You have the music, you have the costumes, you have the choreography and the stage design. You have more than one thing going on. Written, verbal, aural and visual — just the full-on total package.

Dave Holland

British bassist-composer-bandleader who moved to the United States in 1968 to play with Miles Davis

I knew him very slightly. He played on a number of festivals that we were appearing on with Miles’ group and he was in New York at the same time that we all were. The opportunity I had to play with him was a call I got one afternoon to come down to his studio and just have a jam session with him, John McLaughlin and Buddy Miles. It was very loose and a lot of fun, and that was the extent of it. It’s interesting though he had this really long cord and he would walk up to cats and give them a little riff to play and then he’d walk up to someone else and give them a little riff to play. And that’s exactly what Miles did, that same kind of intuitive orchestration.

I think I first heard Hendrix on record when his first album came out in 1967. I just thought it was great because of the looseness, that the music was very improvisational; it wasn’t as regimented as a lot of the music that was being listened to in that period. Miles was interested in all of the music going on around him at the time. He liked Sly Stone’s band and Jimi’s a lot. And I heard rumors — I never spoke to Miles directly about it — but I heard rumors that there was some idea that there may be a collaboration. But it was never more than a rumor, as far as I know.

Hendrix was in Woodstock a fair amount in the late ’60s and he had a musical project that he was doing with local musicians from this area. a more freewheeling kind of thing. His music was growing all the time and there was a sense that he was looking to really expand the horizons of what he was doing. He already had, but I think he still had more of a vision of a collective kind of thing. There was something about his playing that had very much to do with groups and collective playing, interactive playing, which of course is part of the jazz tradition. Well, it’s all coming from the same root, which is the blues. That’s where jazz shares common ground with rhythm ‘n’ blues and funk and all these different strains that have developed out of the blues. I think that Hendrix was sort of playing off the older blues styles — very loose, the interaction with the voice and the guitar. He had some very strong roots in the Delta blues stuff, which is why he might’ve gotten on with jazz musicians. There’s a common ground there.

Jean-Paul Bourelly

Guitarist, now based in Germany, who acknowledged Jimi’s influence on his 1995 DIW recording, Tribute to Jimi

I was nine years old when I first encountered Jimi’s music. My older cousin played me Band of Gypsys and, man, that shit blew me away! After hearing that album I went back and checked out all the other albums. But for me, Band of Gypsys was the ultimate in terms of what he was doing. I thought the rhythm section was perfect for him. Billy Cox and Buddy Miles — those were two cats who could hit! I mean, it was so solid that when Hendrix went into his psychedelic stuff, it was like a perfect contrast. You could see how far he was traveling because the ground was so clear!

Looking back, I don’t think of Hendrix as a jazz player. If you’re talking about a straight ahead style, Jimi wasn’t coming from that place at all. He was basically in love with the blues and R&B and he had all that heavy Indian shit going through his blood too. I guess he was part Cherokee. Jimi had a lot of stuff you can’t really categorize, man. It’s power — just the ability to express things in a very finely detailed manner. Like his vibrato was very detailed, man. Like an opera singer! Very heavy. And the way that a cat goes from note to note, there was a kind of phrasing that he had that singers have. It was very deep, and very seasoned. It had weight.

Hendrix absolutely influenced Miles. I think he influenced every player in jazz who did not block out funk and rock as possibilities to gain knowledge from. He’s the reference for that, just like Coltrane was the reference for improvisational jazz. Any jazz player who found funk and rock and even blues as a reference point to gain something from had to ultimately deal with Jimi. He’s what Archie Shepp calls a transformational player, like Trane, Elvin, Kenny Clarke, Tony Williams Lifetime with Larry Young. All of these guys, through the force of their own playing, basically said, “Yo! This is where the shit is going!” And I hope that jazz can get back to that spirit of respecting and supporting those kind of players.

Dave Stryker

Guitarist formerly with Jack McDuff and Stanley Turrentine, currently with Kevin Mahogany and leader of Blue to the Bone band

I think we’re all affected by the first music that touches us; it stays with us. And so Jimi influenced me in a profound way. It was great to hear that early on in my development: a really creative, powerful, blues-based artist who took a lot of chances. Plus, his drummer Mitch Mitchell played in a looser Elvin Jones inspired way than most rock drummers. Some of his jazzier tunes that I still find amazing are “Manic Depression,” “Third Stone From the Sun,” “Fire” and “The Wind Cries Mary.” There is a tune from the Woodstock album called “Jam Back at the House” that is killing in 6/4. Also, a tune I first heard on the Easy Rider soundtrack called “If 6 Was 9” might be as close to jazz as he got. In the middle solo section Noel Redding the bassist starts walking in a fast 4/4 while the drummer plays half-time rock against it with Jimi blowing guitar and wood flute over it. That song knocked me out when I first heard it and it still does. In fact, I just recorded it with my Blue to the Bone band. I changed the middle section to more of a Miles vibe with the horn section riffing some of his other melodies over it.

Sure, I consider Hendrix a jazz guitarist. He came out of the blues and incorporated that and rock with the improvisational and experimental facets of jazz. Although his tunes were rock-based, his lines swung.

Larry Coryell

Fusion-guitar pioneer began melding rock and jazz as early as 1966 with The Free Spirits. He also jammed with Hendrix after-hours at The Scene before forming The Eleventh House in the early ’70s

Jimi had a trio that sounded like an avalanche coming down off Mt. Everest. Even when he laid out his band thundered on, bringing to mind Miles Davis’ fabled comment: “This black dude made two white cats play their asses off.” I loved that! Wes Montgomery was also playing around New York at the time but a Hendrix performance compared to a Wes performance — I once saw them both the same night — was simply iconoclastic. It was beyond categorization of jazz versus pop or blues. It was a force unto itself. There were, to be sure, elements of the avant garde that was de rigueur in New York at the time in Hendrix’s music. Plus, it was loud — not obnoxious and unpleasant loud like certain counterparts. But it was, at the same time, sweet, romantic, hard, scary, comforting, spontaneous and free in spirit and, because of the extra tones and overtones coming out of the distortion, in the harmony.

The unison of electric bass and guitar of the C&W-type chords in “Hey Joe” sounded not unlike Stockhausen or Stravinsky or the Jazz Composers’ Orchestra, for example. A lot of these similarities with facets of jazz were totally not consciously intended, I’m guessing. Jimi just wanted to play his thing as he saw it. He was like a Mozart surrounded by Salieri. At least when I was around him, he never stopped and let his ego assess his work and compare it favorably or unfavorably with others in a who’s better than who sense.

I may be the only person who hears this, but a few years ago I was listening to "Rainy Day, Dream Away", and it hit me: that's Jimi, doing Mose Allison!

First concert I ever went to.