Where to begin with this guy? First of all, he's probably the only bona fide genius I ever knew. I mean, his recorded output over the past 40+ years is so staggering that it actually makes me exhausted just thinking about it. But to break it down for you, he's averaged about 12 releases per year over the past five years on his fiercely independent Tzadik label, with a remarkable 18 recordings in pre-pandemic 2019. So far in 2023, his prolific output has been reduced to seven new releases, most likely because of time demands from touring with his various ensembles around the country in celebration of Zorn@70 events at Roulette in Brooklyn, Miller Theatre at Columbia University School of the Arts, Great American Music Hall in San Francisco, Walker Art Center in Minneapolis and early this year at the Big Ears in Knoxville, Tennessee.

How is it that one artist can continue to produce so much meaningful music in a single year, let alone over five decades? “Zorn has managed to be so prolific because he has a very gifted way of deflecting distraction,” said bassist-producer and longtime collaborator Bill Laswell, who played with Zorn and former Napalm Death drummer Mick Harris in the hardcore band Painkiller and also was in an improvising trio with Zorn and the late avant garde drumming icon, Milford Graves. “He’s very quick to dismiss anything that might interfere with his moving forward. Everybody’s always coming to you all the time saying, ‘Let’s do this project.’ And he has the ability to say, ‘No, absolutely not!’ He says it authoritatively and sometimes aggressively. But I don’t have that ability. Zorn also knows how to utilize the time very well. As long as I’ve known him, he’d never waste a second.”

“It’s simple,” Zorn once told me over stuffed cabbage and pierogis at Veselka, a no-frills Ukrainian eater in his East Village neighborhood. “I’m insulated against the chaos so I can focus on my work. I don’t have a TV, I don’t go on vacation. Where am I gonna go? I don’t have any children; my compositions are my children.”

Zorn’s creative process is rigorous and monastic. When inspiration hits, he will go into silent retreat in the cramped confines of the same spartan walkup apartment he has lived in since 1977...and not see the light of day until he’s done with the task at hand. During these undisturbed streams of creativity, he will go without food or sleep, sometime for days, finally emerging with a finished work. His joy is in the discovery. “You have to be obsessed with these things,” Laswell said. “If it’s going to be believable and honest, you have to lose yourself in it. That’s the key. And Zorn does that.”

Drummer Joey Baron, a frequent collaborator who has played in numerous Zorn bands, including Spy vs. Spy, Naked City, Masada, Moonchild, Nova Express and The Dreamers, concurred with Laswell about Zorn's fastidious process. "He knows exactly what he wants and he doesn’t stray far from that—unless he hears something that shines a light, and then he’ll take that and see how he can use it within the original concept. And when he does a recording, he’s concerned with every detail, right down to the look of the package. He gets an idea and he follows it through to the nth degree in the quickest time possible. He doesn’t let anything get in the way, from the moment of its inception to the moment of its completion.”

“John demands complete focus and utmost effort from the players, and at times he can be relentless to the point of discomfort," said trumpeter Dave Douglas, a member of Zorn's original Masada quartet. “But when you are in his band, you quickly realize that every action is at the service of his musical vision, with no compromises. It is a profound feeling.”

Another frequent collaborator, bassist Trevor Dunn (Moonchild, Nova Express, The Dreamers, Templar Quartet, Simulacrum), added, "In ensembles like Moonchild or Nova Express, I need to play what is written, maintain tempos, make cues and improvise with a certain intent and in a specific context. In either case, being an integral part of the ensemble is key, and Zorn keeps an eye on us to make sure we are realizing his vision as a composer and interacting within the group in a way that benefits the music.”

Zorn is a seeker. His pursuit is that place between the known and the unknown, the accessible and the inaccessible. And his search is often fueled by his onging interest in mysticism, alchemy and magic. His works like Mount Analogue sustain a mood of wonder and mystery. Composed during a three-week period of isolation and intense creative activity, it consists of 61 musical movements composed randomly. They fell into place with the “click” of recognition that only seems to happen when all the elements of a piece are in perfect balance. It has the air of a spiritual journey; in fact, Zorn fasted for three days while immersed in the project. As he wrote in the liner notes: “Today creation seems to me a magical act—unknown, mysterious, part divination, part prayer, part invocation, part alchemy, part ritual. But at the heart of it all lies deep responsibility. The work and the search are one, and along the way any and all methods must be accessed—new ones invented—if a journey to the inaccessible is to continue.”

Projects in Zorn's ever-expanding ouevre have been inspired by thoughtful deliberation over such disparate and heady topics as the writings of Jorge Luis Borges and the mystical figure George Gurdjieff, the Kabbalah, Christian mysticism and the lunar imagery in Shakespeare's writings. Other subjects he has paid tribute to in Tzadik recordings include poet-painter William Blake, French writer Arthur Rimbaud, Dadaist Marcel Duchamp, Swedish playwright August Strindberg, Dutch philosopher Spinoza, English occultist Aleister Crowley, surrealist painter Hieronymus Bosch and American poet Walt Whitman.

In his liner notes to 2004’s Magick, which includes the five-movement string quartet master- work “Necronomicon,” Zorn wrote: “Music is one of the great mysteries. It gives life. It is not a career, nor a business, nor a craft. It is a gift -- and a great responsibility. Because one can never know where the creative spark comes from or why it exists, it must be treasured as Mystery. For the most part, I believe that creativity chooses you, not the other way around.”

In even more revealing notes from 2011’s Enigmata—a series of 12 genre-defying noise duets with longtime colleague Marc Ribot on electric guitar and Trevor Dunn on five-string electric bass that use atonal written passages alternating with conducted improvisations—Zorn explains his modus operandi in clear, precise terms: “I do what I do regardless of what the outside world might think, want or expect, and although this has alienated my audience, the critical establishment and the academy countless times through my four decades of activity, the feeling that comes from creation on one’s own terms far outweighs any such mundane considerations. I do not revel in the misunderstandings surrounding much of my work, and very much want people to enjoy and appreciate it, but that is neither my motivation nor my reason for creating it. My purpose, my reason, my life—is the work itself: my work, done my way.”

Zorn continues to release a staggering number of recordings each year covering an astonishing array of creative expression, from delicate etudes to throbbing death metal, from moody modern chamber music by his adventurous Incerto Quartet (pianist Brian Marsella, guitarist Julian Lage, bassist Jorge Roeder, drummer Ches Smith) to intimate and transcendently beautiful music by The Gnostic Trio (guitarist Bill Frisell, harpist Carol Emanuel, vibraphonist Kenney Wollesen) and the acoustic guitar trio of Frisell, Lage and Gyan Riley. On the other side of the dynamic coin, there's the bone-crunching intensity of groups like Moonchild (vocalist Mike Patton, bassist Trevor Dunn, drummer Joey Baron), Painkiller (Zorn, bassist Bill Laswell, Napalm Death drummer Mick Harris) and Simulacrum (guitarist Matt Hollenberg, organist John Medeski, drummer Kenny Grohowski).

A roll call of other Zorn ensembles over the years includes Masada, New Masada, Electric Masada, Masada String Trio, The Dreamers as well as the all-star '80s bands like Naked City (Zorn, Frisell, Baron, Fred Frith, Wayne Horvitz and screaming singer Yamatsuka Eye) and the extremely cacophonous Ornette Coleman tribute band Spy vs. Spy (with a two alto sax frontline of Zorn and Tim Berne with bassist Mark Dresser and two-drum battery of Baron and Michael Vatcher). He has also composed 300 tunes in his Bagatelles series that have been performed and recorded by everyone from guitarist Mary Halvorson to cellist Erik Friedlander, electronic percussionist Ikue Mori, guitarists Matt Hollenberg and Daniel Ephraim Kennedy, pianists Kris Davis and Brian Marsella, guitarists Julian Lage and Gyan Riley, drummer Jim Black's quartet and organist John Medeski's trio, and continue to be performed by musicians all over the world.

There are literally hundreds of recorded projects in Zorn's massive discography, all strictly composed vehicles for his fertile imagination. Ideas just seem to pour out of him on a daily basis and he continually documents them, first on paper, then in the studio. His creative faucet is wide open, and it doesn't appear to be shutting off any time soon.

Born on Sept. 2, 1953, John Zorn grew up in Utopia, a section of Queens between Flushing and Jamaica that was originally planned as an alternative location for Jewish families looking to leave New York’s crowded Lower East Side [so named because it was purchased in 1905 by the Utopia Land Company]. His early obsession with movies led to his interest in soundtrack music. At age 13, he saw Phantom of the Opera and instantly fell in love with the sound of the organ, which became his first instrument. He simultaneously followed The Doors keyboardist Ray Manzarek and also soaked up Bach’s organ music. All of this early interest in organ music would ultimately manifest in 2012's solo recording, The Hermetic Organ, on Tzadik. Though he went through a Beatles phase where he played guitar before playing bass in a surf band (while simultaneously listening to Stravinsky, Webern, Ives, Varèse and Stockhausen), Zorn didn’t pick up the alto saxophone until college after discovering Anthony Braxton’s landmark 1969 album, For Alto, while studying composition at Webster College in St. Louis. By 1975, he was ensconced in New York’s burgeoning avant garde scene happening below 14th Street. There followed a quick succession of his game strategy pieces: Baseball and Lacrosse in 1976, Dominoes, Curling and Golf in 1977, Hockey, Cricket and Fencing in 1978; Pool and Archery in 1979. A breakthrough was his piece Track & Field, which Zorn performed on Nov. 7, 1982 with 18 musicians (including guitarists Bill Frisell and Vernon Reid) at the prestigious Public Theater. These were essentially methods of organizing improvisation with large groups by utilizing a prompter to relay “game rules” to the participants, often resulting in some surprising twists.

After operating in the downtown cocoon for 10 years, Zorn broke out in a big way with his 1985 Electra Nonesuch release, The Big Gundown, his avant garde take on the music of Ennio Morricone, film composer for the mid-'60s 'spaghetti westerns' of director Sergio Leone. Zorn followed that success with 1987's Spillane, his noir-ish take on the gritty pulp novels of Mickey Spillane. He subsequently released two more albums on Elektra Nonesuch—1989’s Spy Vs. Spy (his thrashing hardcore take on Ornette Coleman music) and 1990’s wildly eclectic jump-cut project Naked City. Frustrated by being on a major label, he left Nonesuch to record with the Japanese Avant label before forming Tzadik in 1995. And a tsunami of recordings have followed, leading to this current Zorn@70 celebrations.

Once praised by John Rockwell of The New York Times as “the single most interesting, important and influential composer to arise from the Manhattan ‘downtown’ avant garde since Steve Reich and Philip Glass,” Zorn has also been derisively called "the bad boy of new music." But love him or hate him, the impact he has had on music and the music industry over the past four decades is undeniable.

The following two interviews for Jazz Times magazine -- one in 2000, the other in 2009 -- are my way of celebrating this monumental figure in music while also reminiscing about the man himself. On a personal note, I shall always be indebted to Zorn for booking my band, The Hollowmen, at the East Village club 8BC back in 1984, and for appearing at a benefit concert held for me at Tramps in 1987, when I was going through a bout of cancer without the benefit of health insurance. So, thanks for that, John! And thanks for 10 lifetimes of music.

2000 interview with John Zorn for Jazz Times

When I first met John Zorn in 1981, he was blowing duck calls in buckets of water at fringe venues like One Morton Street and Inroads. I would later see him perform at Roulette, Chandelier, 8BC (an East Village club that he also booked) and his own tiny clubhouse on the ground floor of his East Village building, The Saint, where I saw him play duets with Brazilian percussionist Cyro Baptista while setting a cool ambiance before and after his set by playing Grant Green records. Very hip, I thought.

In November of 1982, I saw Zorn with a cast of 18 musicians sprawled across the Public Theater stage premiering Track & Field, one of his sophisticated game theory pieces that involved strict rules, role playing, prompters with flashcards, all in the name of melding structure and improvisation in a seamless fashion. I also recall seeing Zorn playing legit bebop on two occasions -- once playing the music of bebop bassist-composer Oscar Pettiford at King Tut's Wah Wah Hut near Tompkins Square in the East Village, and later performing the music of bop pianist-composer Sonny Clark at the original Knitting Factory on Houston Street. I also witnessed performances by Naked City, Spy vs. Spy and Masada at that same intimate bohemian venue and the premiere of Zorn's Bar Kokhba at the second iteration of the Knitting Factory on Leonard Street in Tribeca. There's been so many Zorn gigs over time -- the original Golden Palominos lineup (guitarists Arto Linday and Fred Frith, bassists Bill Laswell and Jamaaladeen Tacuma, drummers David Moss and Anton Fier) at The Ritz; the November '86 premiere of The Big Gundown at the Brooklyn Academy of Music with 25 musicians on stage (including a battery of guitarists in Arto Lindsay, Robert Quine, Fred Frith and Bill Frisell) in November of '86; Electric Masada (guitarist Marc Ribot, keyboardist John Medeski, drummer Billy Martin) at CBGBs Gallery in 1993. And I'll never forget the night he physically carried iconic free jazz drummer Milford Graves on his back around the concert tent set up on the Hudson River in downtown Battery Park City for the 1998 Texaco New York Jazz Festival. All that plus innumerable gigs at Tonic, the club that Melissa Caruso and John Scott opened in 1998 and which Zorn curated from its outset.

Since forming Tzadik in 1995, Zorn has been incredibly prolific as a composer. He has created a variety of works including string quartets, piano concertos, chamber pieces, music for children, and compelling new music for his brilliant acoustic klezmer-meets-free-jazz band, Masada, featuring Dave Douglas on trumpet, Joey Baron on drums and Greg Cohen on bass. The current discography for Tzadik numbers over 150 [today that figure is well over 400 releases] and includes provocative original material by kindred spirits like bassist Bill Laswell, trumpeters Wadada Leo Smith, Steven Bernstein and Dave Douglas, violinist Eyvind Kang, and drummer Milford Graves, with whom Zorn has performed some scintillating free duets over the past couple of years. He has also performed and recorded with the hellacious power trio Painkiller and Zorn continues to tour frequently with Masada while also playing occasionally with the harmolodic punk-funk band The Young Philadelphians. I spoke to Zorn in the comfort of the same East Village apartment he has lived in for the past 23 years. Surrounded by his imposing and rather sprawling record collection, he spoke candidly about the state of his art, the nature of commerce, and the prospects for adventurous, art-conscious independent labels.

Generally people regard each new year as a chance to reinvent oneself. And I would think the act is even more symbolic as we head into a new millennium.

Every day is a chance to reinvent oneself, but the problem is that we’ve been so beaten down by the powers that be that people are happy to be asleep now. What I’ve been seeing is really fucking depressing and I don’t see anything turning it around. I see enormous corporations acting like slave masters, like the return of the pharaohs. I see co-opting all around. I see McDonald’s everywhere. I see the destruction of what you and I love, the small mom and pop stores-people that love the music and that’s why they have their store. I see that being replaced by Tower, HMV, Virgin. And then I see conglomerates; giant corporations merging together to get even more powerful, like that big thing that just happened with Polygram and Universal. So what are we gonna have in another hundred years? We’re gonna have the world owned by one corporation. We’re gonna have all the artists signed to this one label and anyone not signed to this one label is going to be outlawed. We’re gonna have art police running around looking for small labels and independent artists that are not tied up. And we’re gonna have an inquisition. I mean, we basically have an inquisition now.

But then there are people like yourself and Tim Berne who have taken it upon themselves to push their statements forward on their own terms with their own independent labels.

I agree, but we’re all too rare. I mean, I’m doing what I believe in. I’m trying to do what I think is the right thing, the honorable thing. I’m trying to support the music that I believe in because nobody else is either able or interested in doing it. But do I think that in the new millennium that that is going to take over? No, I’m not so naive as to believe that we can turn the world around. I think this is the way the world has been since the first caveman picked up a rock and knocked someone over the head and said, “I’m the king of the hill.” Greed is a basic part of human makeup and greedy people are usually the ones that push everybody around. And in the time of the pharaohs it was done with violence. Today it’s done in much more insidious ways. It’s done with brainwashing and brain-control. These marketing guys who are at the head of all these companies, they’re really the ones that are spoon-feeding everybody shit. And I don’t really see much hope of turning that around because they’ve been thinking about how to fuck us for so much longer than we could imagine thinking about. They think about that as long as we think about making good music.

I remember when I came to New York in 1980 there was a lot of excitement in the air regarding the music scene. Columbia had just signed James Blood Ulmer and Arthur Blythe and there seemed to be a ray of hope that the major labels might actually begin dealing in more adventurous terms.

But what happened? They put out a couple of records then they dropped everybody. That’s a cycle that happens every 15-20 years.

And then Wynton [Marsalis] came along.

Well, I don’t want to get into personalities and pit people against one another. I think there’s a lot of what Wynton is doing that’s great. I think that solo he took on that Citizen Tain record...have you heard that? That’s fucking smokin’! I mean, this guy can play his ass off. But we’re not talking about musicians. I think for the most part musicians are saints. They give and they give and they give and they get very little back. And if someone manages to get something back, I champion that. They deserve everything that they can get because I think they really put their lives on the line and are giving. I’m talking more about the world that we live in, the machines that we have to fight.

I do think that history is going to have to be rewritten in the next hundred or so years, as it always has been. People that were really popular in their time eventually disappeared and were forgotten. And people who struggled and did it the hard way and concentrated on the music and tried to make something great, eventually their work came to light. It’s often well after they’re dead. It’s rarely in their lifetime and if it is in their lifetime it’s at the end of it, like Harry Smith getting an award the year he died. That’s beautiful in a certain sense and a fucking tragedy in another sense. And, of course, most of the people who are dropping his name now have never even seen any of his films. That’s the world we live in. I don’t see that changing. We have to accept it. It’s very unfair but it ain’t gonna change. We’re not gonna have a fair world in a hundred years. Maybe we’ll see the collapse of capitalism as we know it. Maybe democracy will slowly change and become something that one would hope the people want. But I think that the people who are in power, those kinds of people are always going to be in power. Those kind of people are always going to be pushing everybody around, lining their pockets with everybody else’s money and ripping everybody else off and feeding everybody shit because they believe that people wanna be told what to do. And the sad thing is, most people do wanna be told what to do. They don’t want to get out there and make choices for themselves. That’s another part of human nature. Always has been, always will be.

But now there is more opportunity for independent labels and artists to get their stuff heard through various mediums like the Internet.

You want a ray of hope here in what I’m saying, don't you?

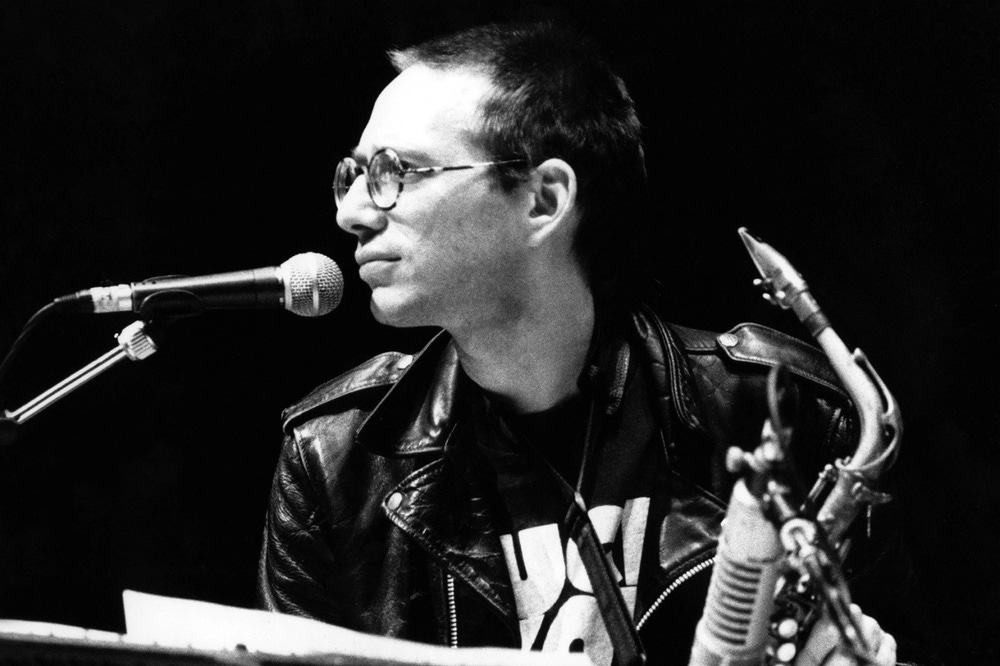

photo by Alan Nahigian

Well, I’m seeing it happen.

Oh, it “happened” in the ’70s. That was a big explosion of independent labels, back when New Music Distribution was around. New Music Distribution provided an incredible service for hundreds of independent labels in the ’70s and ’80s. It was amazing. And it was also amazing that it disappeared. And the reason it went down was greed. Their mafia distribution people decided not to pay them, they didn’t pay the artists and everybody got fucked. Now people can make their own CDs on their own little labels for very cheap-cheaper than it was to make vinyl. They can distribute it through the Internet worldwide; we have MP3, we have downloadable stuff. Information is going to be traded. But I guess what I’m getting at is-who’s gonna want it when everybody’s being brainwashed by these guys who are spending 24 hours a day thinking about how to target certain groups of people, how to control people into wanting shit? That is the big problem-the pharaohs controlling us. Sure, there will be independent artists, always. But they’ll always be on the fringe. And every 15-20 years those major corporations will decide, “Let’s try something new,” and they’ll sign a Blood Ulmer or they’ll sign the 13th Floor Elevators or they’ll sign Captain Beefheart. They give it a chance but it never really works because the figures they’re hoping for are way beyond what these people are capable of.

Some people thought that Columbia signing [avant garde saxophonist] David S. Ware was a very hopeful sign.

It’s not hopeful at all. It’s a freak. It’s the same freak thing that happened when Tim Berne was signed [to Columbia] or when Blood was signed [to Columbia] or when I was signed [to Nonesuch]. I mean, Nonesuch-maybe that’s a little bit different. Maybe [Nonesuch head] Bob Hurwitz has a little more integrity than the major labels. He really believes in what he’s doing. But at the same time, if he wasn’t selling a million copies of the Górecki symphony by some freak of marketing, he’d be out of a job, too-absolutely. I don’t think these companies feel they need credibility in the art market anymore. Blood was signed because they thought they could sell 100,000 copies of it. And then after realizing they could only sell about 50,000-goodbye. There’s no chance that this kind of complex music is going to break into a mass market. No chance. So why bother with it? Why waste the money marketing it at all? It’ll sell what it sells and if it doesn’t sell enough, drop ’em. That’s the prevailing attitude at the major labels and I just see that getting worse and worse.

And yet the fiercely independent artist persists in the face of this adversity and in some cases continues to thrive.

There will always be independent artists, there will always be some freak that says, “This is not right, I’m gonna do it my way.” There will always be experimental music. There will always be people who wanna listen to it. But I just don’t see them taking over the world, you know? Maybe when I was 22 years old I thought we were gonna take over the world, that this was the real music. But now that I have a perspective and I’m 46, I look back and I say, “Look at the history.” Look at thousands of years of how it’s been and how people are manipulated and how greed functions in our society.

How do you see your own place in the scheme of things?

I look out at the world and I see chaos. And that’s kind of the formula for being an outsider. You don’t want to be an outsider, you want to belong and you’re burdened with these human frailties. You need companionship; you need food and drink; you need a nice place to sleep; you want to be understood even though you’re doing something that’s a little difficult; you want your work to be appreciated; you want to be loved. We’re burdened with this. But what we’re doing is we’re creating something that is a little bit scary to most people. It challenges their view of the world. Most people think the world is a perfectly ordered place and they love it. The outsider looks at that and goes, “Man, this is chaos. This makes no sense at all.” And then, they try to tell the truth. And they’re compelled to tell the truth. They can’t help but tell the truth by some inner sense of responsibility.

But you seem to be thriving in spite of the way things are.

I’m not particularly unhappy with where I am right now, or with the scene itself. I think this is an incredibly exciting time for real music. I think there’s a lot going on. And I see new generations coming up being influenced by some of the things that I’ve done and by some of the people that this scene has given birth to. And that’s a beautiful thing. That means that we will never die. That means that death is kind of impossible as this spirit gets passed on in a real, meaningful way. The truth will always be there but you can’t force it down people’s throats. They have to be ready to see it. And, you know, there’s the machine and here we are. And I don’t think it will ever be reversed. I do feel that it’s a lot easier to keep your head clear from greed if you’re not involved with major corporations. When I was working with Nonesuch for a short period of time, I got wrapped up with the same shit of like, “Why does Bill Frisell have a bigger budget than me?” I mean like, that’s something to think about? I could feel greed growing in me like a cancer. And for me, personally, it’s very hard to deal with that kind of shit. Maybe Wynton Marsalis can deal with it; maybe Bill Laswell can deal with it. You know, Bill can sit back and laugh at those fuckers and con ’em and take ’em for a ride. He’s great at talking that talk. But it makes me sick to my stomach, you know? I’m better off as an independent. I’m better off doing it on my own terms. I wonder what would happen to Wynton if he started his own company and did it his way. That, I think, would be a very exciting thing-if he didn’t have to answer to anybody or listen to anybody’s subtle brainwashing-you know what I mean? He’d just have to answer to himself. That’s what I’d like to see, more of that. More of people who are in power taking the initiative to do things on their own without the help of these greedy motherfuckers. Because, you know, money is money. But it’s tainted money. There’s something really evil about those multi-national corporations.

Is the term “jazz” even valid anymore?

The term “jazz,” per se, is meaningless to me in a certain way. Musicians don’t think in terms of boxes. I know what jazz music is. I studied it. I love it. But when I sit down and make music, a lot of things come together. And sometimes it falls a little bit toward the classical side, sometimes it falls a little bit towards the jazz, sometimes it falls toward rock, sometimes it doesn’t fall anywhere, it’s just floating in limbo. But no matter which way it falls, it’s always a little bit of a freak. It doesn’t really belong anywhere. It’s something unique, it’s something different, it’s something out of my heart. It’s not connected with those traditions.

What tradition do you feel close to?

The avant garde. I would like to see the avant garde, experimental music being accepted as a genre in and of itself. I would like to see avant garde/ experimental sections in the major conglomerate record stores. Not just in the stores that have intelligent buyers like Other Music or Amoeba on the West Coast-small stores that are run by people who believe, who hire people who know the music, where you can go to the store and say, “Tell me something interesting,” and they will. Remember that? Those were the days of great record stores.

You worked in one [SoHo Music Gallery] in the early ’80s.

Record stores used to be a powerful source of information. I used to go to Discophile when I was a teenager and say, “What’s new in the experimental/ classical bin?” And the guy would say, “You gotta check this out, it’s amazing.” In ’82, I went to Bleecker Bob’s record store and said, “What have you been listening to? What’s the outest hardcore you’ve heard?” And he’d say, “You gotta hear this Die Kreuzen record. It was on my turntable for six months, couldn’t take it off.” Now you go to Tower and you get these morons that are working for minimum wage that don’t even know where Phil Glass goes. I mean, they don’t know shit about Shinola and they’re working at record stores. Sometimes they’re even buyers and they don’t know what they’re talking about! So no one is getting educated. I’m talking about real grassroots education. That’s where I learned most of my important shit-listening, talking to people, exchanging information. Again, I really believe that this music would probably have a better chance of reaching the audience that appreciates it and selling better if there was an avant garde/experimental section in Tower or HMV. It would be a great clarification of where this music is coming from. Hopefully, that will happen in the future.

What do you think about the potential of MP3, where every musician has his own Web site, where people can download new music, like John Zorn.com?

That’s a beautiful idea. But do you really think these large corporations are going to let that happen? Because these are some greedy motherfuckers and they’re gonna find some way to fuck everybody. People who know how to manipulate other people are always going to be around and they’re always going to be working for those companies and they’re gonna know how to twirl some shiny object in front of some artist and get their fucking publishing away, and get them off their independent dot com and get them onto Warner Bros. Everybody could have their own little record company, it doesn’t cost that much to put shit out. But I get phone calls all the time, I get tapes all the time and I talk to them and say, “Man, you should put this shit out yourself. I’ll run it all down to you on how to do it.” And you know what? They don’t wanna do it! “Man, all I wanna do is make music, I don’t want to think about the business.” And they are ripe for getting ripped off. And most people are really like that. They’re honest musicians with integrity that just don’t want to deal with the business. They don’t want to have their own dot com. And as long as people are like that, they’re victims. That’s been going on since day one.

But more musicians are taking the responsibility to deal on their own behalf.

Boy, I would love to think that. But I don’t think so. I mean, I would love to think that in 500 years everybody’s gonna have their own Web site, everybody’s gonna have their own thing. But I don’t care if material things disappear off the planet and we’re just dealing with brainwaves, there’s gonna be someone who knows how to manipulate that to make more money than anybody else. You know what I’m saying? Power is a drug. Money is part of that. But it’s just the instrumentality of that. I don’t care if there’s nothing on the planet at all and we’re just spirit, there’s gonna be some fuckin’ spirit that wants more than the next one.

You have gained a lot of notoriety in recent years with Masada.

It’s a beautiful band, a powerful band.

Do you ever feel strange being on a jazz festival bill with Masada?

Masada relates to jazz music. It’s my pleasure to play that music on that kind of bill. In fact, it’s exciting to me. And people who never heard it at those festivals might get turned on. Like at the Chicago Jazz Festival, which we just played a couple of weeks ago. It’s a free open-air festival and there were over 10,000 people out there listening to us. We got to play on a bill with Phil Woods, who is one of my all-time heroes. And I got to hang with him a bit, which was great. But is that happening more and more? No, it’s a freak; it’s one in a million. To throw the weirdos a freak gig once in a while. People will listen, they may enjoy it. Maybe they’ll even go out and buy a record and get turned off. Or maybe they’ll keep following. But we’re talking about really insignificant numbers of people.

You’ve traveled a lot with Masada and spread the word by taking the music to the people, much in the same way that Frank Zappa spread his own message.

Zappa was a very special person. He was really articulate; he really cared about politics. He had a lot of things going for him. I can’t step in Zappa’s shoes. I’m not politically aware. I don’t read newspapers; I don’t read magazines; I don’t watch television. So I have no idea. Zappa was on top of everything, man. He was really amazing. I’m not really an articulate, politically minded, forward thinking person with goals that wants the world to be this way or that way. I’m not an interesting interview in that regard. I wish I was. I wish there was someone who could be there in Zappa’s place. I’m not the guy. For me it’s more about doing things than blabbing about it. And that’s another reason why I put a moratorium on interviews. I just felt that not only was I being manipulated or misrepresented or cut down, I also felt that, in general, I just didn’t have that much to say, really. I do music. And a lot of times I don’t really understand fully what it is that I’m doing at the moment. I understand 10 years later what it was. I gotta go on intuition a lot of the time. And I can’t always explain articulately exactly what it is that I’m doing with this new piece. I’m working on a piece now. I’ve never done anything quite like it; I’ve never composed in this way, really. And I feel like I’m taking some chances. But I don’t have the answers to what this piece is going to be or what it’s supposed to be. I feel like I’m going on a trip and I’m discovering it along the way. You get back from a trip and you don’t fully understand what you’ve seen until maybe a few years later, and then you realize, “Oh, wow, that’s how that touched me, that’s how that affected me.”

And to distill it down to one word for the purpose of categorizing music to fit into record bins somehow negates the journey.

Well, those people who categorize are in the business of selling this shit. There is a business side to all of this nonsense, after all, and we’ve got to deal with that. They’re gonna be selling it so we gotta communicate to them in some kind of way. That’s why I’m hoping that maybe there’ll be an experimental section in major record store conglomerates in the near future.

Are you aware of how you have influenced younger musicians just by your own example, by living the way you do and producing music on your own terms?

Well, that’s a beautiful thing to say. I hope that that’s true.

Because you are 46 and there are 23-year-old musicians who are being fiercely independent today because of the groundwork that you laid 20 years ago. I’m thinking of [saxophonist] Briggan Krauss, who has mentioned you in interviews as a huge influence. By example, you have helped him and other young musicians like him to be brave enough to do what they do, against all odds.

Yeah, well, that’s what it takes -- courage. It takes more courage than most people have. There’s less than one percent of people like that, but the world could not exist without them. The world would not move forward without them, and I really believe that. I think the outsiders, the individualists, the people who have a messianic belief in themselves and are able to stick with their vision despite all odds-and believe me, Bill, every day of my life I’m haunted and tormented by the voices of people that are saying in my ear, “Maybe you’re wrong.” But the people that can stick with that, they’re the ones that are really going to make a difference in the world. And they will always be a small number and I’ve always aspired to be one of that number. I think about the people that I admire, people like Jack Smith, who lived in a small apartment right over here on First Avenue and died of AIDS 10 years ago. I worked with him for about eight years in the late ’70s helping him with his theater performances that never more than 10 people attended. And, I mean, this was some of the greatest shit I ever experienced. Here was a guy my age performing for 10 people. And I think about John Cage not getting an orchestra commission until he was over 50 years old. When he was my age he was still working as a dishwasher, you know? I think about that and I say, “Those are the models. I’ve gotta live up to that.” And if I can in any way inspire someone else, then the line gets passed on and that’s beautiful. That’s great. I really hope that it’s happening.

Do you think this music, whether it’s called the avant garde or experimental music, can be promoted properly and sold in greater numbers?

Every once in a while someone comes along who thinks that they can sell this music to a large group of people, but that will never happen. By definition it’s for a small group of people. And I’m perfectly fine with that. I have no bitterness.

What is certain is that this continuum will go on from your mentors through you and on to the next generation.

That continuum will happen, but it will stay very small. But as far as jazz music is concerned, which is a very different subject from my continuum, it’s in the hands of very conservative, greedy people. And it looks pretty bleak. There will always be a few things like that incredible solo that Wynton took on that Citizen Tain record. And that’s great that that’s there. I wish he did that all the time. But if he did that all the time maybe he wouldn’t have a major record contract, maybe he’d have to give up too many things that he’s unable to give up right now. Or maybe he’s just not into doing that kind of music. Whatever it is, it’s his choice. I mean, he’s an intelligent person. But I do feel that getting involved with these greedy money people, these slave masters, these pharaohs, can be very damaging to your health. You can catch that disease. Greed is a very infectious thing. And you gotta be really insulated and really careful and really keep your head clear to avoid it.

And you’ve succeeded in doing that over the past 20 years.

Because I don’t deal with those fuckers. That’s how I’ve done it! But if I were still making records for a major label I’d be just as sick as they are. And frustrated. I isolated myself completely, deliberately. Because I asked myself, “How much longer am I on this planet? How much time have I got?” So I choose not to watch TV. Instead, I choose to work. I decided I have to cut out all distractions so I can concentrate on what’s important. And staying in this apartment has really helped me do that. I could’ve moved uptown to a big place, bought a brownstone, had a garden room and a whole big thing. But I’m very happy here. This is where I’ve done all my really creative work. It’s happened right in this room, you know? This is where Cobra was conceived; this is where Spillane was conceived; this is where I wrote Aporias. I mean, this is a great room! I’m very happy here. And it keeps me focused. And like Jack Smith, who lived in this small apartment on First Avenue, it keeps me in touch with what’s important, with the people that nurtured me. This is a great neighborhood with a lot of energy. When this building was built it was for immigrants coming in who couldn’t wait to get the hell out of this neighborhood, but it had a lot of hope in it, you know? This was the jumping off point for people who succeeded in the world out there, who came from Europe and escaped the Nazis. And that feeling of hope is still alive in this building. I feel it. Ginsberg and Kerouac lived in the apartment on my second floor. There’s a bit of history there. There’s incredible history in this neighborhood. Bird lived down the street. That kind of energy doesn’t go away, even with all these yuppies moving in and mom and pop stores turning into chain stores. That’s what’s scary, the co-opting of the world. That’s why I think eventually it’s going to be one big corporation and they’re gonna be out hunting people like you and me. Insurrection is a dream, but it ain’t gonna happen. Not in our lifetime. They have so many ways of keeping us under control-with drugs, with the media, with language. I mean, these guys have been thinking about this shit for decades and decades-or centuries-how to control the masses. I wouldn’t be surprised if there was a chip in every single computer that’s being sold today that actually made it into a camera with a microphone so that everybody could be monitored. It would be so fucking easy; you know what I’m saying?

That’s been prophesized. Big Brother from Orwell's "1984," no?

Absolutely. But you can go cuckoo with that shit. I mean, I’m not that “out.” I isolate myself but I’m still living here in the city. I’m not in some shack somewhere thinking and plotting out all of this shit.

But the point is, you’ve eliminated distraction from your life so you can focus on the work.

That’s right. I’m insulated. I think people need insulation. Like before I was talking about how the outsider looks at the world and sees chaos. The person who’s in the world with their regular bourgeois values, they see an orderly existence. They’re insulated in their way because they don’t want to wake up and look at the truth. The outsider is insulated in their way so that all that chaos doesn’t destroy them. And that’s the harder road. You know, ignorance is bliss. It’s hard to stay on the outside wanting to be on the inside, climbing up the cliff, just hanging on by your fingernails. I mean, every year I hear how another musician has gone down, either decided to quit because he’s so frustrated or was suicided by society. It’s hard. I wish there was more support, more positive energy from the critical world toward people that are really on the edge trying to do shit. I wish there was more attention given to that music. It’s tough all around and we just have to stick together. And we will. I’m not going anywhere.

What are your own personal goals for the new millennium?

One of the beautiful things in my life is that I don’t really have any goals. I just work day by day and do my thing. I don’t dream about operas on the Metropolitan Opera stage, I don’t dream about that big philharmonic commission. I work with my materials that I have here at my hand with the musicians that are here and I’m very happy taking little baby steps one at a time.

You’re not dreaming of the big house in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, with a two-car garage?

No, no. I’m happy here with my little two-floor apartment. I’ve been here for 22 years; I’ll be here all my life. I had an apartment in Tokyo for a while and that was a dream. It was a tiny little place that was not much bigger than this and it was like $300 a month, but I let that go. Sometimes I think about Indonesia-getting a little hut or something. But, come on-I’m a New Yorker. I’m not gonna get on the plane for 20 hours to sit on the beach for a week. That’s a nightmare! So I don’t have a lot, really. I’m not that kind of dreamer.

2009 interview with John Zorn interview for Jazz Times

Think of John Zorn, the American composer, alto saxophonist and conceptualist, as a juggler. Zorn keeps aloft a plethora of radically different projects while also heading up his own label (Tzadik) and acting as artistic director at the Stone, his own cutting-edge performance venue in Manhattan’s East Village. A restlessly creative spirit with a seemingly inexhaustible supply of energy, Zorn is, at age 55, experiencing unprecedented productivity in a career that dates back to the mid-’70s, when he began experimenting with like-minded improvisers and musical renegades on Manhattan’s Lower East Side who, together, forged an alternative movement that would be identified by critics as the “downtown” scene.

“I feel like things are really flowing now, like I’ve hit kind of a peak and I’m riding it,” confessed Zorn during an interview at the Ukrainian restaurant Veselka, a favorite East Village haunt for artists, thinkers and assorted bohemians. “I’m riding the wave and the wave is taking me further. People have told me that with Virgos, your life is like a crescendo. It begins and it slowly gets better and better and better. What better life to have?”

On a Tuesday morning in early February I met Zorn at the Ontological-Hysteric Theater at St. Mark’s Church in the East Village for a dress rehearsal of “Astronome: A Night at the Opera,” his audacious and powerful new musical/theater collaboration with renowned playwright and avant-garde theater pioneer Richard Foreman. A mind-boggling visual explosion featuring a relentless flood of psychedelic, dreamlike imagery and sacred Jewish symbolism, it is fueled by the unbelievably intense soundtrack of Zorn’s Astronome, performed by his extreme hardcore noise trio Moonchild (Joey Baron on drums, Trevor Dunn on fuzz bass and Mike Patton on wordless banshee-scream vocals). The music is so loud and intense, in fact, that warnings are announced before each performance at the Ontological-Hysteric Theater, along with offers of free earplugs for the faint of heart. (The production was filmed for future DVD release which will be available on Zorn’s label Web site, www.tzadik.com).

That Friday night I attended the U.S. premiere of Zorn’s new Masada sextet, an expanded edition of his long-running Masada quartet (Zorn on alto sax, Dave Douglas on trumpet, Greg Cohen on bass, Joey Baron on drums), augmented by outstanding pianist Uri Caine and Brazilian percussionist Cyro Baptista. This group, which combines elements of the classic Ornette Coleman quartet with the Eastern European flavor of traditional klezmer music and Jewish sacred music, is undeniably in the jazz camp, albeit traveling on its own unique tributary off the mainstream. Their invigorating sextet set at the Abrons Arts Center on the Lower East Side, marked by some stellar individual soloing and an uncanny group-think, represented a new level for this band that Zorn formed 15 years ago. Caine brought aspects of both Cecil Taylor and Bud Powell to the table while Baptista colored the proceedings in typically wacky and intuitive ways, resulting in a decided raising of the bar over all other previous Masada performances.

The following night, Saturday, Zorn debuted new material with his surprisingly accessible group The Dreamers (Kenny Wollesen on vibes, Marc Ribot on guitar, Baron on drums, Dunn on bass, Jamie Saft on organ and piano). While Moonchild may be in the ultra-extreme zone and Masada may come across as challenging to the uninitiated, the music of the Dreamers is relaxed, engaging and downright delightful. A blend of pop, exotica, funk, surf rock, minimalism and world music crafted as little three-minute melodic gems, it is the yin to Masada’s yang.

It’s hard to imagine that the music I witnessed on these three separate occasions over the span of a week was conceived by the same mind. And yet, it’s only the tip of the iceberg for the remarkably prolific Zorn. As the head of Tzadik (since 1995), he also shepherds new bands onto the label, providing them an outlet and nurturing them under the auspices of his Radical Jewish Culture series, Film Music series, New Japanese series, Oracle Series (promoting women in experimental music), Key series (promoting notable avant-garde musicians and projects) and Lunatic Fringe series (promoting music and musicians operating outside of the broad categories offered by other series).

And then there is Zorn’s own incredibly rich, pre-Tzadik legacy: an extensive discography of well over 100 recordings as a composer of string trios and string quartets, film scores, game theory pieces, chamber pieces, classical works and meditations on Jewish mysticism, British occultist Aleister Crowley and pulp-fiction author Mickey Spillane (1987’s Spillane), as well as tributes to figures like Ennio Morricone (1986’s The Big Gundown) and projects as a leader with the bands Naked City, Painkiller and Spy vs. Spy (which performed hardcore renditions of Ornette Coleman compositions).

Some of Zorn’s jazziest playing on record can be heard on such recordings as 1986’s Voodoo by the Sonny Clark Memorial Quartet, 1988’s News for Lulu and 1992’s More News for Lulu (featuring interpretations of tunes by Kenny Dorham, Sonny Clark, Freddie Redd and Hank Mobley), as well as recordings with the great early ’60s Blue Note organist Big John Patton. He also makes a cameo appearance alongside his all-time alto sax hero Lee Konitz on the 1995 set The Colossal Saxophone Sessions, playing a version of Wayne Shorter’s “Devil’s Island.”

In 2006, Zorn received a MacArthur Fellowship grant (a five-year grant of $500,000 to “individuals who show exceptional creativity in their work and the prospect for still more in the future”). And in 2007 he was the recipient of Columbia University’s William Schuman Award, an honor given “to recognize the lifetime achievement of an American composer whose works have been widely performed and generally acknowledged to be of lasting significance.” He was more than deserving on both counts.

Zorn has also edited a series of books titled Arcana: Musicians on Music, which contain essays by various colleagues including Derek Bailey, George Lewis, Bill Laswell, Steve Coleman, Dave Douglas, Nels Cline, Fred Frith, Wayne Horvitz, Marty Ehrlich, Vijay Iyer, Elliott Sharp and dozens more. The fourth Arcana book is due out this spring, as is a new recording by the Dreamers, their third on Tzadik. Notoriously leery of interviews, Zorn nevertheless granted this sit-down and subsequent photo shoot for JazzTimes. He was unusually forthcoming and positively bubbling over in anticipation of the opening of “Astronome: A Night at the Opera,” which, as of our interview, was scheduled to run through April 5. I spoke with Zorn a few days after his gig with the Dreamers at the Abrons Art Center.

Your output over the past 30 years is staggering.

Well, I’ve been busy. I guess it’s really hard to stay current with what I do because I put out like five, eight, 10 CDs a year. Most people who try to write about what I do just don’t have any sense of the scope and the range. And even if they were given a pile of 25 CDs or something, a lot of them just aren’t equipped to deal with something that’s as far-ranging as the Crowley String Quartet performing “Necronomicon” on the Magick CD and then to what you saw with Richard Foreman, the Astronome project, really heavy rock, to jazz-based music with people like Dave Douglas and Joey Baron, to the film scores to the Dreamers and on and on. There’s a lot of different music and unless you’re open to all that and acquainted with it in the first place, it’s just going to go in one ear and out the other.

I read somewhere that this is all the result of what you call “an incredibly short attention span.”

Well, that’s just some 1980s hype where Nonesuch Records was attempting to sell me as some kind of postmodern phenomenon. It’s their job to sell product, and in order to sell product they need to market you in a certain way. But I don’t think that that is a very intelligent analysis of why someone likes a lot of different kinds of music. It’s not a matter of having a short attention span, it’s a matter of living in today’s world and being a curious, creative, open-minded, intelligent individual who appreciates greatness for its own sake without putting it into any kind of academic or cultural box.

And what you bring to it is this incredibly intense focus, which is a rare commodity these days.

That’s who I am. For instance, I just got off the phone with the census bureau and they asked me how many hours do I work in a week. And my answer, basically, was I work 24 hours a day. Even when I’m sleeping I’m working. I’m talking with you, I’m working. I get up first thing in the morning, the computer goes on, I’m answering e-mails. I go out to lunch, I have a discussion with someone, it’s about music, it’s about art. I go to a museum. Even in the cab I’m on the phone doing business. I’m always working. My life is making work. That’s why I’m here. People are surprised that it’s possible to get as much work done as I do. It’s very simple. I choose to work. I don’t go on a vacation. I’m not interested in that.

I found it very revealing the other day when we were sharing a cab ride and I made some humorous reference to a scene from 'Seinfeld,' and you had no idea what I was talking about.

Right. I’ve never even seen it.

And I remember thinking right after I said that, “Wait! He probably doesn’t even have a TV.”

Right. Well, this is actually not so difficult to understand. The world is filled with distractions, and we understand why it’s good for the government, especially in an administration like Bush’s, to bamboozle people and keep them distracted from getting together and saying, “Wait a minute! What is going on here?!” I choose not to be distracted. I figured out, I guess sometime in the past 20 or 30 years, exactly what it was that was very distracting about our society and what was stopping me from making work. And I managed in a very simple way to cut that out. I’m not sticking my head in the sand; I’m just eliminating anything that gets in the way of making work. That means a lot of sacrificing, even to the extent of, you know, having a family. You have kids, you have to devote half your life to your children to be a correct parent. I can’t do that. I am devoted to my work. So my children are the compositions, the records, the performances. And my family? That’s the musical community. And that’s why it’s not an unusual thing for me to create the Stone or create Tzadik. That’s what a father would do to put clothes on the back of their children or make sure they get to a good school or protect them if they’re being bullied. I’m here to help the community that nurtured me. And that’s why no TV; that’s why I don’t read magazines or newspapers. I focus on the art that I’m doing. That’s my gift for the world; that’s why I’m on the planet. I’m not a hard-liner and I understand how difficult it is to survive in this world, but at the same time I think the reason I created Tzadik, the reason that the Stone had to happen, the reason that these Arcana books are coming out, the reason that I continue to create work to the extent that I do, is because I created my own avenue.

I got the impression from seeing The Dreamers the other night that you’re a guitar maven in a certain way because you seemed to take such great delight in some of Marc Ribot’s slashing guitar solos.

Well, I’ve worked with some amazing guitar players in my time: Fred Frith, Arto Lindsay, Bob Quine, Derek Bailey, Henry Kaiser, Bill Frisell, Marc Ribot. Right there is kind of like a history of experimental guitar in the 20th century. Those are great names; these are really amazing players. And I’ve always had a very close relationship with guitar players.

Did you ever have a personal connection to guitar? Did you ever play the instrument yourself?

Yeah, I used to play it when I was a kid, sure. We all played guitar. I played bass in a surf band. I learned Beatles, Stones and Beach Boys tunes on guitar. I was really into surf rock when I was like 10 years old. So sure, I played guitar, bass and all like that. And in a way, the guitar is what the violin was in the 18th-19th century. It is the voice of the people. It's a very important

instrument. If you’re going to be a composer today you have to understand not just what the guitar can do but what the electric guitar can do, because that is one of the new instruments of the 20th century, along with the drum set and the electric organ and the saxophone, and now, the turntable. These are new instruments and you need to include them in your language. It’s here, it’s available. If Mozart were alive today, believe me, he’d be incorporating all those instruments and writing for them. And he would also be listening to all this different music that is around. It’s not an unusual thing for a creative person to be interested in creativity. People who grew up at the time that I did, in the ’60s, we loved all different musics. We loved rock, we loved jazz, we loved classical, we loved world music. We had a hunger for anything new. We’d make little mix tapes on cassette that had all these different styles of music. That was like a very special thing. We’d play them at parties. Now, that’s normal, that’s the iPod shuffle. Everybody listens that way now. So in that sense, we have really succeeded. It’s like our generation, our kind of impetus of loving all these different things, that is kind of the new way to listen to music.

It’s true.

And one thing that I have to say, which is interesting on kind of a socio-cultural level of how this music has been misunderstood-understood, marginalized-glorified, this is a new music. There is a music that is kind of post-’60s and that music is a very pluralistic music, a music that incorporates and accepts all these different influences. These people that we’re talking about, whether it’s Fred Frith, Marc Ribot, Wayne Horvitz or Uri Caine, these are people that love all kinds of music and listen to all kinds of music. And they had access to all kinds of music and created something with that, with all their loves. And it’s a new music. Maybe Uri’s a little more in the jazz camp coming out of Philly with his background, maybe Fred Frith is a little more in the rock-folk camp. Everybody has different roots in different places. Ultimately, I thought of myself as more of a classical musician who then got involved with different kinds of players. But the music is not jazz music, it’s not classical music, it’s not rock music. It’s a new kind of music that was loved by people like yourself and other writers who were on that scene in the late ’70s-early ’80s. You loved this music, you were stimulated by it, it said something to you because it came from your experience. But where can you write about this music that you love? What are the outlets? The only outlets were jazz magazines. Even though it didn’t belong in that tradition or in that format, it was the only format that there was. So I feel like that created a deep misunderstanding in what this music is. People started judging this new music with the standards of jazz, with the definitions of what jazz is and isn’t, because stories about it appeared in jazz magazines. And now I’ll do a gig at the Marciac Jazz Festival and I’ll get offstage and Wynton Marsalis will say, “That’s not jazz.” And I’ll say, “You’re right! But this is the only gig I’ve got, man. Give me another festival and I’ll play there.”

Well, he couldn’t possibly have said that about Masada.

Actually, he said it about electric Masada, which, admittedly, is pretty out there. It has elements of [my game piece] “Cobra” in it, it has elements of my conduction kind of stuff. Plus, (Marc) Ribot and (keyboardist Jamie) Saft really take it to a little more of a rock area, and there are always some structural elements of classical in there. Some people want to try and define it and say it’s related to Third Stream.

What you’ve created with Tzadik is a label identity that is like ECM or Blue Note, Prestige, Windham Hill, where if there were any record stores left, Tzadik would have its own bin.

Well, that’s a thought. And a lot of record stores do have a Tzadik bin, which is kind of one way to do it. We have almost 450 records on our label already and there has not been one dedicated article or feature in any United States magazine or newspaper on this label. Is that incredible? And of course the answer is simple: We don’t send review copies out, we don’t play the game, we don’t kiss ass, we don’t put ads in newspapers or magazines, and if we don’t scratch their back they’re not going to scratch ours.

And yet you have cultivated this pretty sizable audience around this label.

Some of our records sell 40-50,000 copies. And it’s a worldwide audience. Of course, some sell 500 copies. But it’s structured in such a way that the ones that sell help the ones that don’t sell. So we manage to stay afloat in kind of a socialist paradigm.

Bruce Lundvall has the same scenario happening at Blue Note, where the successful million-sellers like Norah Jones help the more esoteric projects.

He continues to do what he believes in and it works in the marketplace. I was never a believer in applying for grants. I don’t like to put my hand out to somebody and say, “Please help me.” I just went and did what I did and I managed to survive in the marketplace. I understand how some people can’t do that and need the grant process, but I find the grant process itself is so demeaning. Immediately, it’s like you’re asking daddy for a handout, you’re being judged by people who have no right to judge you, and if you do get the grant it’s usually half the money you asked for two years too late. By that time, you’re already onto something else. I’ve seen artists on Tzadik who tried to get grant proposals through to make a more ambitious record, and I’ve seen new records get completely derailed for five years. In one case, I said to an artist, “Look, I’ll give you a little extra money. Let’s find a way to do it just on our own.” And he said, “No, I want to do it right, I want this extra money. Let me wait.” And I said, “Well, what if you don’t get the grant?” Five years later we’re still waiting. And the fact is, he’s already on to another thing.

What is the average budget for the records you do on Tzadik?

At first it was just always $5,000; now we’ve gotten a little more flexible with it. Now if someone breaks even on their first record we’ll give them $6,000. If they break even on their second record we’ll give them maybe $7,500. If they break even on their third record, we’ll up the ante a little bit. But if their first album doesn’t break even we either reduce the budget or say, “Let’s wait until this one sells more and then we’ll do a second record.” But we try to be very economical in the way we work because we can’t afford not to. The music we’re making is meant for the world; it’s meant for everybody to enjoy. But I’ve learned that some projects that I do, like the Dreamers, will do very well. We’ll sell 20-30 thousand copies of that because it’s popular music that people can really enjoy. But if I’m going to do an esoteric project about Aleister Crowley with the “Necronomicon” string quartet or something that’s really more challenging, which I’m compelled to do and these artists are compelled to do and the world needs, I’m not so naive as to think that that’s going to sell 30,000 copies. With a younger unknown artist, something esoteric like that will sell 500 or 1,000. With me, maybe it’ll sell 5,000, but it’s not going to sell 30,000. And that doesn’t break my heart anymore because ultimately this music is for the few. It’s meant for everybody, I want everybody to love it and enjoy it as much as I do, but I can see that that’s just not possible.

So business is good with Tzadik?

As the music industry crumbles before our eyes and major companies are now going belly-up and people aren’t buying CDs, Tzadik is standing like a fucking oak! We have very modest sales, we break even every year … maybe make a little, lose a little, but we basically break even every year. So we’re still standing here and sales are pretty consistent. We did really well this past year. People that believe in this music purchase this music.

Let’s talk about The Dreamers. I was delightfully surprised by this group. Where is this charming music coming from?

Well, it comes from my love for music that does delight and charm. I am a big fan of Les Baxter, Martin Denny, Arthur Lyman, the pioneers of exotica. I’ve been a fan of that music since I was young. It was part of my upbringing; it’s there. You can hear elements of it here and there in my music over time. You hear it in Bar Kokhba; even in things like Godard and Spillane there are moments that sound like that. This Dreamers project, I think, was bringing together all of these beautiful musics that I love, from world music to surf music to exotica music to different kinds of funk and blues. I put all of these things together and created something that, for me, was meant to charm and delight.

And you did it within these three-minute little gems of melody.

Yeah, little instrumental gems. You and I grew up at a time when there were instrumental hits. Henry Mancini, Jack Nitzsche, Miklós Rózsa-they did film scores but they also had hits that were played on the radio. But the concept of the instrumental hit has almost completely disappeared because greedy record executives understand that vocal music is going to sell five times or 10 times more than instrumental music. That’s just the way it is.

I think the Beatles phenomenon made people in the industry go a bit crazy. They saw the money that could be made with vocal groups.

It did indeed. And I don’t know whether the Beatles themselves are responsible for the disappearance of instrumental music. I wouldn’t put it that way. Because at that time, “The ‘In’ Crowd” was an enormous instrumental hit for Ramsey Lewis, Max Steiner’s “Theme From a Summer Place” was enormous. There were tons of great instrumental hits back then. Maurice Jarre’s “Lara’s Theme” from Dr. Zhivago was a hit, “Telstar” by the surf band the Tornados was an enormous hit in 1962.

Al Hirt, Duane Eddy and Herb Alpert all had instrumental hits in the early ’60s.

Yeah! This was music that was backed by record companies, promoted by record companies, who were just trying to make some money. And they managed to make money with that music. And were fine with it. Now they’re just not gonna waste their time with it when they can make so much more money with a vocal performance. So instrumental music doesn’t have the same impact on our culture that it used to, and I’m sorry about that. It still has an impact on me, though. I devote my life to instrumental music and the Dreamers is just another form of instrumental music.

You mentioned Martin Denny and some others as having an impact on you growing up. What about Burt Bacharach?

Of course! Most of what he did was vocal but harmonically he was way advanced, and also in terms of time signatures, he was always experimenting. And he had a few instrumental pieces that were absolutely wonderful that I love. Sure, Bacharach is absolutely an influence. There are so many influences in the Dreamers. And again, each piece is kind of a unique little thing, its own little world.

I thought I may have also heard some MJQ and Dave Brubeck influences in there too.

Yeah, Ramsey Lewis and Booker T & the MGs, the Meters. These were all amazing instrumental bands. You can hear some of that influence in there as well. So you know, the Dreamers is a charming project of beautiful music. And it’s been very successful. It’s a kind of very beautiful world that I hadn’t dealt with before, but elements of “Cobra” or Electric Masada are still in there.

The sound of The Dreamers is engaging rather than challenging like Masada.

You don’t always have to challenge the audience. Sometimes you want to challenge the musicians to keep them engaged in what you’re doing. And that’s something that’s always been at the forefront of my modus operandi. I don’t just write music, I write music for musicians to play. I want them to be psyched about what they play. I want them to be engaged, because if they’re bored, the audience is going to be bored. I want them to be on the edge, to be surprised, to be delighted. I want to have fun up there. Ultimately, it’s all about love-if we love each other and we love what we’re doing, some of that love is going to go into the audience.

You have already released several volumes of Masada CDs since 1994, but you’ve really taken it to another level with this new sextet edition of the group.

I think you’re right. I think that the concert you saw the other night was one of the best concerts we’ve ever done. It’s like the old joke with the Masada quartet: “What was our best gig? It’s the next one.” Because it was always getting better. But I felt like we kind of hit a plateau a little bit with it in 2007 and I said, “Well, maybe the quartet is really done. Maybe

we’ve accomplished what we can accomplish. Maybe it’s time to put this to bed.” And then I was asked by the Marciac Jazz Festival to put together a slightly larger group. They asked me what if I added a couple of people to Masada and I said, “I can’t add anybody to the quartet. The quartet is the quartet, that’s what we do.” But then I thought, “Well, if I was going to add someone I would probably ask Uri and Cyro.” So we tried it at Marciac and it was unbelievable. We didn’t even have any rehearsal time. I just passed the charts out and said, “OK, just watch me because I’ll be conducting. Let’s just do it.” And it was one of those magical clicks on the bandstand that sometimes happens. So yeah, this band is taking off again. After 15 years of doing this music, we can still find new things.

And certainly Wynton can identify this new Masada sextet music as jazz.

Absolutely. With Uri’s presence, that is clear. It’s the most jazz-sounding thing I’ve ever done.

And there's also that connection to Ornette’s quartet, which comes in and out.

It’s in and out. Maybe it’s not there as much as it used to be. I think there’s as much Miles in the approach with Dave and Uri and in the way the group kind of breaks down to a single solo piano once in a while, or trio sections within the context of the group before coming back together. There’s always a lot of surprise there. So, yeah, it is definitely stronger in the jazz tradition with Uri in the band. And I think Uri and Dave have a really strong hookup. They’ve worked on a lot of projects together and Uri has also played in Dave’s quintet, so there’s some magic formula going on there. And then you add Cyro Baptista to the mix, crazy Cyro with all his sounds. I’ve been working with Cyro for 27 years and he never fails to surprise me from night to night.

I remember you guys doing a duet at your former club The Saint back in 1981.

There you go! Yeah, man. And this is another thing that I think is important to mention is the longevity of these relationships that I’ve had with musicians. When I find someone to work with, we continue to work together because we believe in the same things and we love doing what we do. If Bill Frisell were still living in New York, I’d be working with him still. But he moved out to the West Coast and it’s just too hard to get together. So it’s been Cyro since ’81, Joey Baron since ’84, Dave Douglas since ’94, Uri more recently, and then you’ve got Ribot, Greg Cohen, Mark Feldman, Erik Friedlander, Trevor Dunn, Mike Patton … these are all people that I continue to work with. It’s a tight community; it’s a real community. It’s a community the way we see the bebop community was in the ’50s or the existentialist community was in Paris or the abstract expressionists in the ’40s in New York, which was a community of people that got together, that talked about art, that were inspired by each other and that created a very strong artistic statement that had impact on the society. We’re doing the same thing. We’re living in the same area, we’re meeting all the time outside of musical situations, we’re talking, we’re communicating. This is a real scene in the best definition of that word. It’s creative, it’s inspiring, there’s less competition and more encouragement. Marc Ribot is delighted when I do well. I’m delighted when he does well when he does a project. It’s good for everybody. When Ribot’s onstage, I want him to play his best. I’m not trying to throw banana peels under him to slip so that I can smoke him onstage. That’s not the point. We’re all focused on music and we all want each other to sound as good as we possibly can sound. And when I get people in my projects, I feel like they sound the best that they can sound. They’re killing! And that’s what I want, that’s what I encourage. And that’s what the compositions are meant to do.

You know who you sound like now? Joe Zawinul. He would say the same thing, man. He’d always say, “My band, I put this band together for these guys to be killers!”

That’s right. And there’s a lot of other people that don’t think that way. The band is about them. They’re the leader, it’s all about them; they don’t want anyone to sound better than them. So they keep them under wraps, they push them down, they don’t give them solo space. They don’t let them express themselves. You need to have a certain rein on people so that the compositional integrity is kept intact. You know, there’s a frame around a composition and there are things that belong in the frame and things that don’t. And it’s the bandleader-composer’s job to make sure that everything fits. But the most important thing is to keep that balance, where everything belongs but the players are injecting themselves into the work and doing their best. Duke Ellington was a perfect example of that.

And Frank Zappa.

Yes, though Zappa in the earlier years. Then it got a little different for him. He got more and more into control. For me, in his later years, his best record is Jazz From Hell, where it’s all done on a Synclavier.

Yeah, I think his comment at the time was, “At last, I’ve found my perfect band.”

There you go! It’s him playing everything. Well, I don’t think that way. Because the lesson I learned from Zappa was that you treat your band members like royalty. You give them as much money as you can afford to give them on the road, the best situations in the hotels, treat them to meals, thank them for their work, appreciate their creativity and just thank your lucky stars that they’re in your band working with you.

I’ve read that Ellington loved his band and always treated his musicians well.

I think that’s really one of the secrets of making great music that is not unique to the 20th century. I think Mozart understood that, I think Bach understood that. I think that great composers were performers and understood what it was like being in a band. And they wrote for players who could get onstage and feel excited about what they were doing because they just looked fucking great doing it. No one wants to look like a fool onstage; you want to look good. You want to play music that makes you look good, and I think composers understand that too. And the ones that have a sense of the performer side of it are the best composers, the ones that came up in a band. Ellington never stood in front of a band waving his arms; he was playing piano, he was part of the group. When Steve Reich came up, he was always playing percussion in his group and still does in a lot of cases. Phil Glass too. They understood what it was to be a performer, and that made their compositions so much more deep. That’s something I never wanted to lose.

And here you are about to turn around another Dreamers project in just a few months.