A Birthday Salute to Stanley Clarke

Reminiscing about my first interview with the great bassist nearly 50 years ago

Bassist-composer and hero of my youth Stanley Clarke turned 73 just a few days ago (on June 30). Hard to believe. But then, I’m turning 70 in a few months. Even harder to believe! The Philadelphia-born bassist was the subject of the very first interview that I ever got paid money for back in 1975 for Milwaukee’s underground weekly, The Bugle American. Run by a renegade band of hippie journalists with a decidedly leftist bent, The Bugle was cast in the mold of other counterculture weeklies that sprouted up around the country like New York’s The Village Voice, The Syracuse New Times and San Francisco’s The Bay Guardian.

I had covered a few local governmental meetings and neighborhood political rallies for The Bugle as a budding reporter studying journalism at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, still a year away from my summer internship at The Milwaukee Journal, the city’s daily newspaper. But on this lone occasion editor Gary Peterson allowed me to cover something that I was personally more interested in. So when I submitted (on spec) an interview that I had done with bassist Clarke the day after his appearance with fusion supergroup Return To Forever at the Performing Arts Center in downtown Milwaukee on April 7, 1975, he bought it. And to my astonishment, it ran across four pages in the Bugle, with photos. That officially marked my beginning as a professional freelance music writer, an occupation I have maintained for what will be 50 years coming up next May.

Return To Forever had come to town to perform at the PAC’s Uihlein Hall, home to the Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra, under the direction of conductor Kenneth Schermerhorn. RTF’s record No Mystery had just come out, the second album to feature a fleet-fingered fretboard flash from Bergenfield, New Jersey named Al Di Meola, who was three months shy of his 21st birthday at the time of this performance (older than me by just two months). I had already been enamored by the whole fusion movement, having seen the Mahavishnu Orchestra in concert (opening for Frank Zappa at the Milwaukee Arena in 1973) and avidly following Return To Forever through their transformation from acoustic, breezy, Latin-flavored ensemble (documented on 1972’s Light as Feather) to high voltage electrified juggernaut (beginning with 1973’s Hymn of the Seventh Galaxy and continuing with 1974’s Where Have I Known You Before). Add in recordings by Weather Report, Larry Coryell’s The Eleventh House, Klaus Doldinger’s Passport and, of course, Tony Williams Lifetime and Miles Davis seminal fusion outings like In a Silent Way, Bitches Brew and On the Corner, and I was all-in for the F-word. So naturally, I was primed to see Return To Forever when they rolled into town on that fateful day in 1975.

I had also been well acquainted with Clarke’s incredibly original slap bass playing by then from digging his self-titled solo album from 1974, which contained the ultimate jamming vehicle, “Lopsy Lu,” powered by none other than drummer Tony Williams and featuring Jan Hammer on synth and Bill Connors on electric guitar.

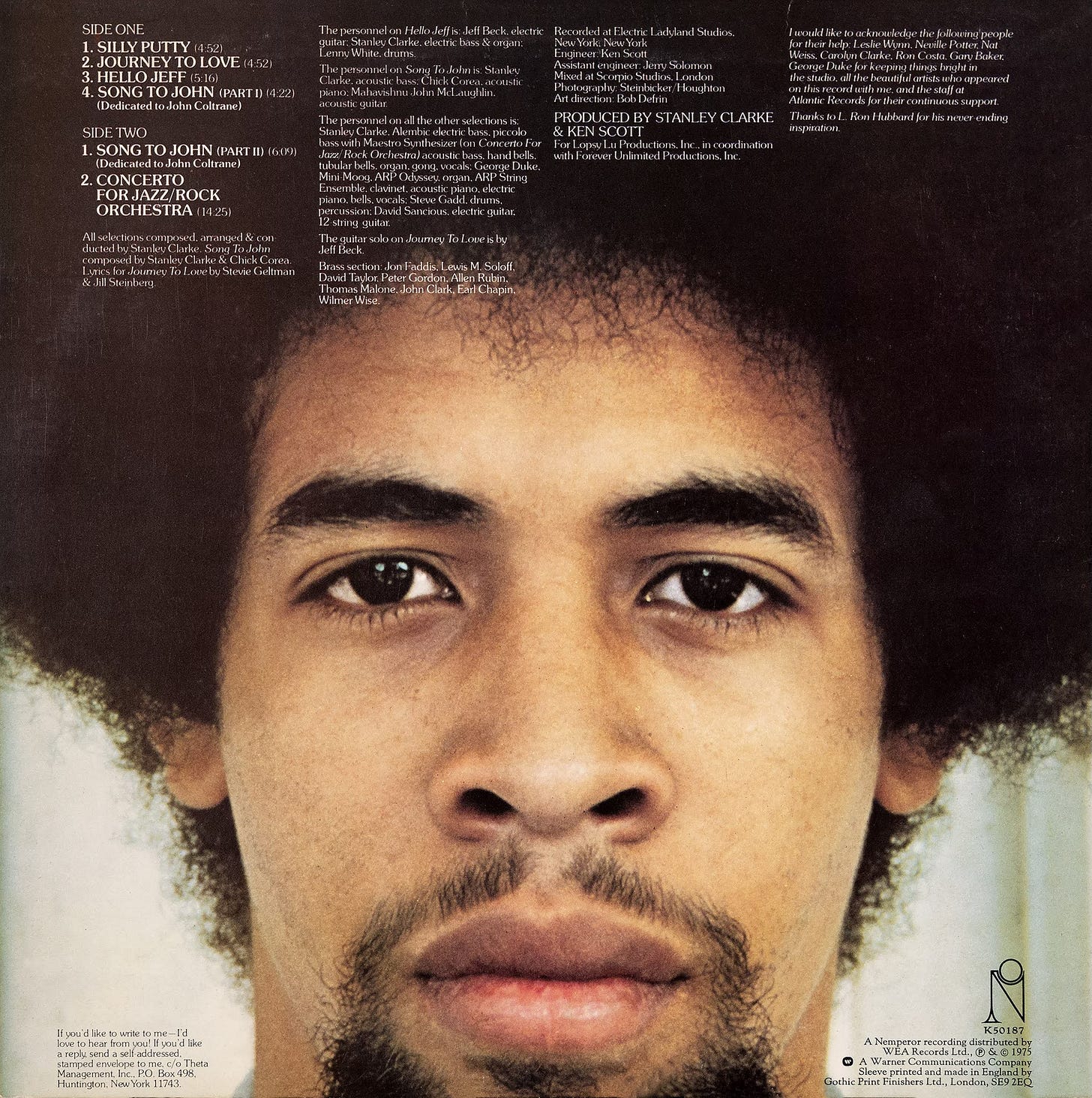

Clarke’s 1975 followup, Journey to Love, included a guest appearance by guitar hero Jeff Beck on “Hello Jeff” and the title track. And the amazing acoustic trio number, “Song to John,” featured an all-star assemblage of Stanley on upright bass, Chick Corea on piano and John McLaughlin on acoustic guitar. That inspired song remains a favorite of mine to this day.

Following the Return To Forever concert at Uihlein Hall, I went backstage and chatted briefly with Chick Corea and Al Di Meola and Lenny White. And I made an appointment with Stanley to come by the Marc Plaza Hotel the next morning to conduct an interview with him before he left town. Here, in its entirety, is that Q&A interview with Mr. Clark, printed in the May 21, 1975 edition of The Bugle American:

Stanley Clarke has come a long way from his days of playing background music for Campbell’s soup commercials in New York. The-24-year-old musician from Philadelphia has since toured the country playing for Horace Silver, Stan Getz, Pharoah Sanders, Joe Henderson, Gil Evans... the list goes on and on.

More recently, he has gained international fame as the extraordinary bass player for Chick Corea’s Return to Forever band. Downbeat magazine named him number one electric and number two acoustic bass player of the year in a recent Critics Poll, and his latest solo project, 1974’s Stanley Clarke (on the Atlantic/Nemperor label and featuring keyboardist Jan Hammer, drummer Tony Williams, guitarist Bill Connors and percussionist Airto) is garnering rave reviews from critics. Clarke’s next solo venture being released this June (Journey to Love, also on Atlantic/Nemperor) will include guest appearances from Jeff Beck, George Duke and Steve Gadd. He also plans to record an album late in June with Mahavishnu John McLaughlin, Tony Williams and Alice Coltrane.

Away from the rush and pressures of playing 25 concerts a month throughout the world, Stanley relaxed in his small Marc Plaza hotel room following Return to Forever's Milwaukee performance. His long wiry frame stretched out on a bed cluttered with clothes, guitar cords and suitcases as he watched Dick Johnson and The Bowling Game on tv. After all, what else can a touring musician do when he hits Milwaukee.

He turned the sound down on the tv and picked up his piccolo bass, a peculiar instrument with an abnormally high octave range, and sounding somewhat like a sitar. That special bass was designed by Stanley and built by Carl Thompson for Clarke's summer recording sessions.“Electronic music is happening, it's all around,” he said while running his spider-like fingers up and down the neck of the bass at a blinding pace. “I’ll bet you if we turned on this radio we’d hear something electric.”

“Electric music is happening, it’s all around. I’ll bet if we turned on this radio we’d hear something electric.”

Silencing the ramblings of Dick Johnson’s tv bowling show, Jimi Hendrix’s “Voodoo Chile” came pounding through the speakers of the TV/ radio in his hotel room as Stanley broke into a huge, sly smile and began bopping his head. He grinned and looked out of the comer of his eye as if to say, “HA! What did I tell you.”

Hendrix also just happened to be one of Clarke's early idols, along with Miles Davis and John Coltrane. “Jimi would have had a whole new musical form of his own by now, but he let himself die,” he said. “I know cats at Electric Lady Studio in Greenwich Village who were real close to Jimi and said he was just an irresponsible person. All he wanted to do was smoke dope, fuck chicks and play music — which may be fine. But I know you have to live this life with a body, so I don’t abuse it.”

Bugle: How does playing in Return to Forever differ from playing with people that you had previously toured and recorded with, like Stan Getz, Horace Silver and Pharoah Sanders?

Clarke: Those bands weren’t real bands, they were just gigs. Those guys were like figureheads — leader type guys. And they would hire some other guys to play with, sort of like a backup band. It was that type of feeling where I was like a sideman.

Bugle: So it was all laid out for you and you just had to fill in?

Clarke: Sometimes. But at the particular gig that I didn’t dig, there were leaders who didn’t lay anything out. But they were the leaders and they got a lot of the credit. It would be like “The Joe Smith Band,” but there would be all these other guys in the band writing music and doing this and that who never got any recognition.

Bugle: What is the situation like now with Return To Forever?

Clarke: I can create this band more. Chick and myself are the charter members of the group so we’ve been creating it for the last four years. I can write things now, change things around, be the way I am, and it feels good.

Bugle: Why did you and Chick form Return to Forever?

Clarke: I was looking for a band in which everybody had an affinity for everybody else. Everyone allowing everyone else being-ness — the space to be yourself and grow.

Bugle: Did that exist with the other groups?

Clarke: It didn't have the same thing that we have now. Of course we communicated, but it was on different levels -- it was very limited. Usually, those bandleaders weren’t into talking a whole lot. I had a leader once where the only thing I ever said to him was hello and goodbye and, “How much money do I get?” Other guys were into coke and that trip, which is fine, but it’s nice to talk.

Bugle: What influenced the transitions in Return to Forever’s path from acoustic to electric?

Clarke: The changes came from noticing what was happening in this environment. When the band came out, we played light Latin music and it was fun. Then we decided, “Hey, let’s play some electric music.” I pulled my electric bass out of the closet and started playing that again, and it was fun too.

Bugle: Does your style of playing differ from acoustic to electric bass?

Clarke: Sure, but it all depends on what emotions I'm creating. With the acoustic bass I can create real soft, subtle emotions or I can get very intense on the acoustic — try to kill, beat the instrument. And it’s the same with the electric bass.

Bugle: How did you choose the bass as your instrument?

Clarke: At the age of 13 1 was given a violin, but I couldn’t make it because my hands were too big. The cello had the similar problem — just too small. I even played some tuba in school but I finally came to an upright bass and stuck with that.

Bugle: How did your jazz influences enter?

Clarke: My parents bought a new stereo and with the system came a demonstration record. It was a jazz record with all the great jazz artists of the time — Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Miles Davis, Charlie Mingus. And I listened to that shit and I said, “Man, I don’t know what this is!” But I liked it and I tried to play along with it until I finally I wore that record out.

Bugle: How did you first get involved on the jazz scene?

Clarke: I went to college at the Philadelphia Music Academy for about two years, then decided it wasn't what I really wanted to do. I wanted to play in front of people, so I left college and came to New York. I joined a band with Horace Silver and stayed with him for about a year. From that point I just played with everyone who came along — Stan Getz, Pharoah, Lonnie Liston Smith and others.

Bugle: How important is communication for this band?

Clarke: It's the whole reason why we’re here. Communication is a nice thing. You can do it in many ways -- words coming out of my mouth or notes coming from my instrument. A lot of people in Vietnam are communicating with bullets, believe it or not. It’s really wild but that’s what level they’re at. The highest form of communication is music because it’s very thin. Words like “communism” convey a bunch of heavy pictures of Russia and all that shit, but if I play one note you get a feeling that’s softer and more aesthetic. You don’t need words to communicate feelings.

Bugle: Did you lack this type of communication with the other bands?

Clarke: Compared to the degree of communication that we have now, it was like nothing then. I remember joining Pharoah Sanders at the peak of his career, but he changed his music and he slowly began dying out. It was because he wasn’t communicating anymore. Nobody was getting his creation.

Bugle: Do you feel that Miles is communicating with his more electrified music today?

Clarke: Miles Davis is an institution. Miles could come on stage and fart for the rest of his life and there’s always going to be some people there who will like it or hate it. But Miles’ whole scene now is playing games on the people, like turning his back to the audience when he plays or spitting on the stage and shit like that.

Bugle: Do you think his music is too complex for mainstream audiences to appreciate?

Clarke: No, that’s just the trap that people fall into when they see something they don't understand. They think it’s so high and fantastic. But that’s bullshit. The most complex music there is can be understood by anyone if it’s put across with sanity. I'll give you a real example. There’s this tune that Chick wrote called “Beyond the Seventh Galaxy.” Technically it’s a motherfucker — I can’t describe how complex it is. But the effect of the piece comes off simple because there’s four guys playing their asses off on it. Now, you can take four guys that could play the same piece and say they’re fucking off, that nobody’s playing together — one guy is drunk and the other guy is over here looking at some bitch. It’ll come out sounding like shit because you won’t get that same simple effect produced from four guys playing their asses off, all hitting it at the same time.

Bugle: So the strength of the piece is in it’s unity?

Clarke: In any group where you have four guys that sound like one it’s so simple and beautiful. In this whole planet people are striving for some kind of unity, although sometimes it’s hard to tell. There are these unifying groups — the Black Movement, the White Movement…and I could see 25 years from now maybe both movements will get together and call it Black And White Power. Whatever happens, art will be the only thing that will keep the sanity on this planet.

* * * *

Clarke, whom I had regarded as the Jimi Hendrix of the electric bass (for his wildly charismatic Afro hairstyle and his long spidery fingers that seemed ablur on his 4-string instrument) came into my orbit about a year before I had ever encountered Jaco Pastorius, who would later consciously make the link to Jimi in his solo bass medleys at Weather Report concerts by routinely quoting from “Purple Haze” and “Third Stone From the Sun.” I caught Clarke countless times since that initial interview in 1975.

There was the New Barbarians tour of 1979 where he shared the stage with the Rolling Stones’ Ron Wood and Keith Richards on guitars alongside keyboardist Ian McLagan, saxophonist Bobby Keys and The Meters’ funky drummer Zigaboo Modeliste. The Milwaukee date was plagued by rumors (from Woods’ manager and the Milwaukee concert promoter) that certain “special guests” would be making appearances at the show. The names of Mick Jagger, Bob Dylan, Rod Stewart and Jimmy Page had been promised and/or hoped for, and when none of them materialized for the April 29 concert, a riot broke out at the MECCA (Milwaukee Exposition and Convention Center and Arena). Angered fans charged the stage at the end of “Jumpin’ Jack Flash.” Forced back by police, the scuffle turned into a melée (as described by Billboard) as fans smashed chairs and broke windows. The police arrested 81 people.

“There was a lot of X-rated stuff going on,” Clarke told Vintage Guitar magazine in a 2016 interview. “It was a complete rock-and-roll tour—the kind you read about in magazines. Just what you think a rock tour should be. Everything was there—bells and whistles, perks, the extras…all the ups and downs.”

In 1981, Stanley launched the Clarke/Duke project with former Zappa keyboardist George Duke, which I caught at the Beacon Theater. There was also a memorable gig on Oct. 13, 1984 at New York’s The Bottom Line, where Jaco joined fellow Philadelphian Clarke on stage for a whirlwind jam. Two bass gods trading licks. (Opening for the Stanley Clarke Band that night was yet another Philadelphian, jazz guitar great Pat Martino, who was making a comeback after suffering a life-threatening brain aneurysm four years earlier).

On February 5, 1988, I caught Clarke at The Ritz in New York with the Jazz Explosion Superband, featuring guitar god Allan Holdsworth, trumpeter Randy Brecker, keyboardist Bernard Wright and drummer Steve Smith. An odd gathering of talented artists, each a bandleader in his own right, they nonetheless turned in a potent version of Charles Mingus’ “Goodbye Pork Pie Hat,” which Stanley dedicated to the late Jaco Pastorius (who had passed away on Sept. 21, 1987).

I later saw Stanley with his fellow RTF bandmate Di Meola and former Zappa and Mahavishnu violinist Jean-Luc Ponty on their Rite of Strings tour in 1995. Fast-forward to 2006 and I caught Clarke in a mind-boggling bass triumvirate, featuring low-end colleagues Victor Wooten and Marcus Miller, at a Bass Player sponsored convention in NYC. That initial concert led to them forming the supergroup SMV and releasing their debut album, Thunder, which was released on August 12 of 2008. A week earlier than that SMV release, on August 7, 2008, I attended a Return To Forever union with Clarke, Corea, White and Di Meola at the United Palace Theatre in my Upper Manhattan neighborhood of Washington Heights (one of the rare gigs in my lifetime that I could actually walk to). In June of 2011, I caught the Stanley Clarke Band with rising stars Charles Altura on guitar and the incredible Ronald Bruner on drums at an electrifying gig at New York’s Blue Note. In November of that same year, Clarke returned to the Blue Note to play in an ‘unplugged’ edition of Return To Forever with Corea, White and Elektric Band guitarist Frank Gambale as part of Corea’s 70th birthday celebration at the famous New York nightclub.

On March 21, 2012, I caught the acoustic Stanley Clarke trio at the Blue Note with piano prodigy Beka Gochiashvilli (from the country of Georgia) and RTF bandmate Lenny White, doing Chick Corea’s “No Mystery.” Then on Nov. 6, 2012 I was happily in attendance at the Blue Note once again to witness Chick Corea with Stanley Clarke, Ravi Coltrane, Charles Altura and Marcus Gilmore. It was the last time I would see Chick and Stanley play together. I’m probably forgetting half a dozen Stanley Clarke gigs along the way. Suffice it to say, my firsthand accounts of this tall, talented man are plentiful and go back 50 years. Oy! Am I that old already? Seemed like only yesterday that I was ducking thrown chairs at that New Barbarians concert in 1979.

A soundtrack to my teenage years!

Great interview, so candid, and the “trip down memory lane” of your concert experiences is sending me to the record shelf. Heard RTF in Grand Rapids, MI, in ‘76 following “Romantic Warrior,” and they opened with “Hymn If the Seventh Galaxy.” The upperclassman we went with, who played jazz, were flummoxed. My best friend and went bonkers. His brother played in a local fusion band and had opened for Weather Report locally and owned all of RTF’s records, so my friend and I knew and loved what we were getting into. At The Aquinas College Field house. Chick’s rig was insane: two giant metal frame speaker racks divided into quadrants that held these clear acrylic domes cover with various size tweeters.